Director of the Gujral Foundation and Outset India, Feroze Gujral has supported prodigal talent in recent years, espousing unexpected causes in the Indian art world. With a career in fashion and the luxury business spanning almost three decades, her transition to a keen commentator of cultural philanthropy has been quiet so far. In a rare, first such interview, she speaks with Mayank Mansingh Kaul on her vision for the arts in India, ideas that preoccupy her voraciously, and directions for future projects.

Mayank Mansingh Kaul (MMK): We have known each other from the fashion and design spheres, and I have seen what was an instinctive interest in culture in you transform over recent years into a very focused area of persuasion. What would you attribute this to?

Feroze Gujral (FG): I grew up in a family that was traditionally a patron of the arts. Culture was a way of life! We were surrounded by music, dance and literature…my parents were patrons of the Louvre and the Smithsonian. Also, in Muslim families like ours, there is a tradition of giving away two percent of everything one earns. This was also true of what we received as pocket money as children – one was always encouraged to give back, by showing how grateful one is for the privileges life has given us. The idea of involvement in the arts, now, when I think about it, is perhaps only natural as a way of giving back to society for me at a fundamental level.

I also spent my early years living in North Africa and Europe, from Egypt to

France, which were both countries of incredible history and cultural wealth. As a teenager, I was struck by how much one had access to in terms of cultural institutions, museums and libraries, all of which seemed to be missing when I returned to India. I am always the NRI kid who looks at India from the outside and is always wondrous about its infinite treasures and opportunities. Having married into an artist family, I was lucky to be surrounded by artists, dancers, writers and poets… our home was constantly graced by an endless stream of creative people. Both my husband Mohit and I have shared a common love for art, design and architecture through the years. In recent years, however, I have noticed a lack of infrastructure for the arts in India. From the mundane to the monumental, there is a lot to be desired. There are amazing collectors with incredible collections, but unfortunately, there are very few institutions where one can view art in public spaces. The question begs to be asked.

What legacy do we leave for our children? The city of London alone has about 240 museums; Berlin has one on every corner! India has many museums, but how many do we really know of or ever visit? Most are derelict and dust laden. These random threads of thought have led us to believe that even the smallest of efforts and initiatives could perhaps lead to a change in how we look at ourselves. For it is only through the arts that history remains.

MMK: You channel support for the arts through The Gujral Foundation and

Outset India. Can you share more about the focus of each organization?

FG: The Gujral Foundation had been funding higher education in the arts, the

fight against malnutrition, WWF, Teach for India and so on for the past 15 years and it is only since 2008 that we restructured the foundation’s focus to art, design and culture. Most of our funding today goes towards our own art initiatives, outreach projects, talks and symposia, and specific kinds of support to other art institutions.

As my father-in-law (Mr. Satish Gujral) enters his 90th year, Mohit and I are keen to look at our own collection of his works, and work on the possibility of archiving and presenting this collection to the public. This has led us to intensively research and review what has been done internationally for private collections. We were looking at putting all his artworks through the years in a singular space. Outset India’s main mandate is to programme public art projects, and we hope someday we’ll be able to align with the original mandate of Outset internationally, which is to become a prominent acquisition body for museums.

MMK: Through Outset India you have supported unusual and risky projects. Has that been a deliberate intention?

FG: The projects are chosen completely instinctively; that we hope will instigate a conversation. So far, yes, we have supported Indian artists who have not had much exposure in India. Sonia Khurana’s solo last year at 24, Jor Bagh was one such instance. As was the recent presentation of Tejal Shah’s work which could otherwise never have been shared in a gallery in India because of its provocative content. This support has also been, equally, to mediums of art like performance and sound art, which also have limited platforms to be presented in this country.

MMK: So, in some ways are you trying to fill in the gaps?

FG: We are simply doing what we can do with the resources we have, in a small

and impactful manner. We support through funding, to begin with. Further, with physical spaces and real estate – The Toilet in Mehrauli and 24, Jor Bagh, are relatively smaller examples. In Kochi the main venue, Aspinwall House has been given to The Kochi-Muziris Biennale for both editions in collaboration with our partner DLF. At the moment the nature of such support is experimental and organic. There is no hard and fast structure to our programming, the main intent being to showcase diverse and interesting artists and work that provokes thought and feeling.

MMK: You have also spoken of your interest in addressing policy-related matters…

FG: Yes, Mohit and I do believe that some simple policy changes reflecting the best practices in the world would greatly help the Indian art movement, as it stands today. We need greater interactions with the global art scene. In this regard, we have pushed very hard and managed, in collaboration with other individuals, to get a Corporate Cultural Responsibility policy to be included under the Corporate Social Responsibility Act. This allows individuals and corporations to get a tax break for cultural endeavours. Similarly, we are pushing hard for more institutional areas to be defined, so as to enable the private sector to invest in the building of cultural institutions at a subsidized, more affordable real estate investment.

The other area of one’s interest is in changing the taxation policy of importing and exporting art. One has to begin with the essential policy that has not been updated. The world over, funding for the arts is seen as prestigious and highly profitable. The business of benevolence is a powerful legacy-building business that can be self-sustaining. Apart from this, there is an enormous amount of revenue generation by nonprofit institutions which allows for progressive forward funding. In the UK, a huge portion of their annual GDP comes from cultural tourism. In France, every French president has a mandate to build a few cultural institutions during their tenure. China’s policy of encouraging the private sector to invest in culture building by underwriting the price of the land is pushing the country to invest in their own artists, creating institutions for them, and hence creating crucial value for their work.

MMK: I want to come back to this aspect of the business and the market, within the art ecology that you are trying to address – but for now I want to ask you about the idea of institutions. The word comes up frequently in your responses. Are you moving towards setting up an institution?

FG: For the time being, we are thinking of working within existing institutions

and strengthening them through specific kinds of support. This is certainly

on our minds. We want to be associated with great world-level institutions, work with them, and co-build cultural platforms for engagement and practices within them…

MMK: Despite your clearly having so much to say about the arts in India, why have you chosen to be reclusive to the press about your role here, then?

FG: This has been a conscious decision. I have a very strong media persona

connected to the world of fashion and luxury. I feel there is a need for a gap before I am ready to comment more publicly on matters that are important to me in the arts. The work one does is there to be seen. The projects that require publicity such as our upcoming exhibition at the Venice Biennale will of course have the required press and PR required.

MMK: You have also very categorically chosen to not enter the space of such

support to the arts, as a collector of contemporary art… Do you have any collecting practices?

FG: We have a very large collection of my father-in-law’s works and we are

constantly buying back works to fill in the gaps towards a comprehensive collection. The contemporary art we have bought is not planned in any way, it’s instinctive. We buy what we love! The allocated funds that we deploy through the foundation are purely for funding. We do however have a traditional approach in investing, most of which is in real estate, which we are beginning to think of using for more art projects – there is a defunct ceramics factory in Okhla in Delhi, some land in the industrial area in Gurgaon…

MMK: What further directions do you see yourself growing in now?

FG: We certainly want to consolidate the momentum of what we have been doing in the last few years. But specifically, apart from working with institutions as I have shared before, I am interested in linking ourselves to connecting Indian art to more global platforms. I think this is a huge dearth in India, of conversation and critique. Also, I find that there are no collective platforms, therefore no collective views, ideologies and movements.

MMK: I am curious Feroze, none of the conventional reasons people get into philanthropy in the arts can be applied to you. You certainly do not need the

social capital that often such efforts can accumulate. Nor is this so far allowing you any kind of indirect PR, and not that you need it either. Yet you speak about the business of such philanthropy…

FG: Yes, one has been blessed, quite early in life, with a certain amount of recognition, both by the virtue of belonging to an eminent family, as well as through one’s own work in the fields of fashion and media. I speak of the business of philanthropy because it is a business. It requires the same investment of an idea, time, energy, people and hard work. Its rewards are much higher than monetary profit as it gives one legacy, a public platform, and the power of giving and builds a vast and diverse community, which is a very exciting and fun proposition. I hope to incentivize people to invest in the arts in a more potent way. Philanthropic endeavours give you a different kind of power from money and fame, but it allows you an equal calling card. It is a privilege to be able to give back to society and one’s country. I truly believe that the profits that come out of being benevolent are sometimes equal if not greater than mere financial profit. The greatest examples are the Rockefeller family, Peggy Guggenheim, Andrew Carnegie… We know their names because of their philanthropy, don’t we?!

MMK: There has been much excitement about your plans to support the collateral exhibit at the upcoming Venice Biennale. I am particularly happy that you have chosen Natasha (Ginwala), an old friend, to curate this. It provides a much-needed platform for young, talented curators…

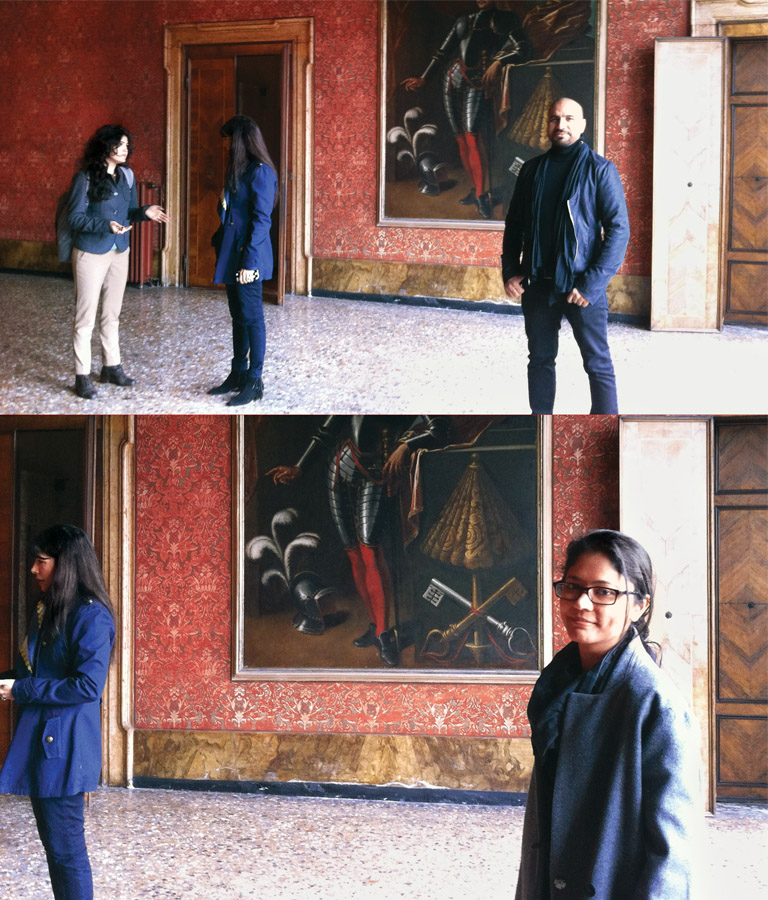

FG: We are thrilled that the Biennale committee has selected this project as a collateral event! We are proud to present ‘My East is Your West’, an exciting project that brings together artists Rashid (Rana) from Pakistan and Shilpa (Gupta) from India in dialogue, based on the initial concept of a jugalbandi, which means the entwined twins or the eternal response. We are showcasing the event in a spectacular location – the Palazzo Benzon. I am delighted to have on board Natasha Ginwala, our young and exciting curatorial advisor and programming curator. We are also partnering with Martina Mazzotta of the Mazzotta Foundation for outreach and educational programming around this project.

Image courtesy: The Gujral Foundation