Dr. Amin Jaffer is the international director of Asian art at Christie’s, his role encompasses the development of Christie’s brand and business within India and internationally. Formerly he was senior curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

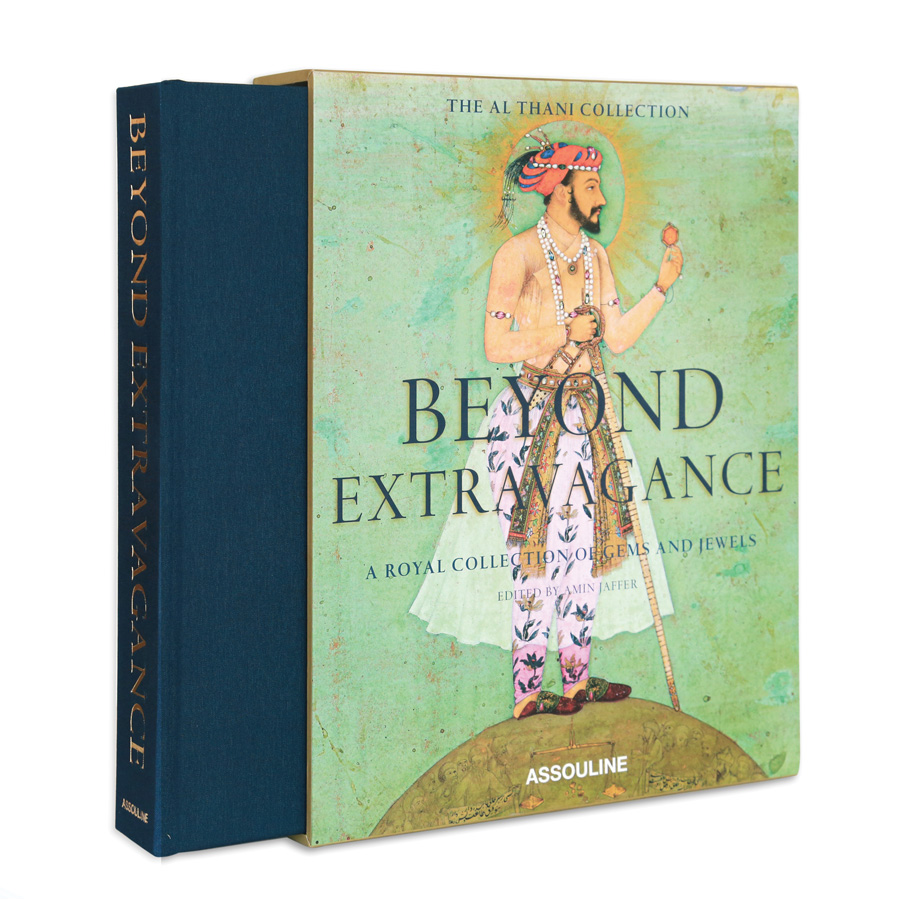

Apart from organising and contributing to multiple symposia and exhibitions, he is the author of the path-breaking volumes – Furniture from British India and Ceylon (2001) and Made for Maharajas: a Design Diary of Princely India (2006) and is the co-editor of Encounters: The Meeting of Asia and Europe: 1500-1800 (2004) and Maharaja: The Splendour of India’s Royal Courts (2009) which accompanied blockbuster V&A exhibitions that he cocurated. Jaffer also curates the Al Thani collection, recently producing the generously illustrated Beyond Extravagance: A Royal Collection of Gems and Jewels (2013).

When not writing about rare magnificent objects, Jaffer curates contemporary art, raises funds for museums and public projects, currently advising the Gujral Foundation on a South Asia pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year.

Art critic Bharti Lalwani catches up with Jaffer for a brief conversation on his early years, his role at Christie’s and his personal aesthetic inclinations.

Bharti Lalwani (BL): Amin, you are an individual of a hybrid background with multifarious interests beyond your role at Christie’s; let’s start with your early years. As an Indian born in Rwanda and spending your formative years in

Kigali, you have since lived in Europe, Canada and England for your education.

Do you think your diasporic experiences have lent you a certain criticality by virtue of being the uncomfortable outsider?

Amin Jaffer (AJ): I feel less of an outsider in today’s world; we all seem to lead such multi-national and multi-ethnic lives nowadays. But when I was growing up – until I was 24 or so – I felt that my identity was rather fractured in that I had no true home and wherever I was, I felt somewhat out of place. This led me to identify with works of art that are themselves hybrid, born from the encounter of different cultures and outside of mainstream art history. This fascination inspired my earliest books and exhibition projects.

BL: From my own personal experiences as an Indian diaspora in West Africa and later in Southeast Asia, I would wager that it is this discomfort that bestows an ability to delve beyond the superfluous, tend to local contexts while effortlessly crossing over cultures and easily adapting. Are you especially drawn to art that expresses this somewhat amorphous quality?

AJ: The unlikely works of art resulting from historic cultural exchange are an

ongoing fascination. An example is the late 18th-century ivory-veneered Adam-style armchair made in Murshidabad that triggered my interest in Western-style furniture made in colonial India and led to a doctoral thesis on the subject. The great jewellery commissions by Indian princes from European jewellers are another manifestation of the same phenomenon.

BL: You spent 13 years as a curator at V&A since 1995, publishing a number of

gorgeously illustrated books that brought readers close to the luxurious world of India’s royalty. Could you tell me about the challenges you faced as your career began at the public institution?

AJ: The greatest obstacle, of course, was securing a permanent position at the

Museum. From 1995 to 2002 I was on a series of short-term postings associated with the research department but for which there was no secure funding. Deborah Swallow, then keeper of the Indian department (now

director of the Courtauld Institute of Art), was my mentor and championed

my research, recognising that studies in marginal areas made an original

contribution to the wider field of Indian art. I did not find that the V&A itself

offered obstacles as such, only opportunities. My fellow curators were interested and supportive and the directors I worked under were open to my various ideas and projects. The V&A’s own collections and archives provided a foundation for my research while the institution offered me a strong platform for engaging with scholars, curators and collectors around the world. As a child, I had been collecting catalogues that the V&A had produced about their European decorative arts collection; working in the institution was a dream come true.

BL: I’m rather taken by the fact that you were already collecting the museum’s

catalogues as a child! I’m embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know what a ‘museum’ was until much later but your early interest hints at the disposition of your family…

AJ: Neither side of my family were art collectors but my mother’s family was

bookish and throughout my childhood, my mother gave me volumes about Indian art and history, classical mythology and Bible studies and so on. We were lucky to be in Europe frequently and I remember, aged six, being taken to the Louvre and Versailles, followed by other major museums, such as the Vatican and Accademia when I was nine. The British Museum and V&A were favoured haunts since early childhood, along with the Tower of London, Hampton Court and houses like Blenheim and Longleat.

BL: Were you always particularly drawn to hybrid furniture, textile, porcelain

or objects that are an amalgamation of different stylistic elements and

craftsmanship?

AJ: Hybridity defined my interests in those years, whether panels of Japanese

lacquer in French 18th-century furniture, Chinese export porcelain or the use

of Indian trade textiles as wrappers for Japanese tea ceremony vessels. These

were produced by one culture for the consumption of another. This is not to

say that I didn’t admire the balance and beauty of art works born out of specific cultural contexts or works that are representative of an unadulterated taste; it is just that culturally-mixed works of art seemed to raise questions that were closer to those that I was asking myself.

BL: In terms of the complexities that art is able to raise — in turn urging introspection on the viewer’s part, is there one artwork that comes to your mind that has been most rewarding in this sense?

AJ: It is difficult to speak of only one artwork; as a genre, I have always considered Namban lacquer ‘arrival’ screens to be particularly significant, representing the 16th and early 17th Japanese fascination for foreigners and the exotic goods they traded.

BL: Do you collect? Is there a criterion you adhere to?

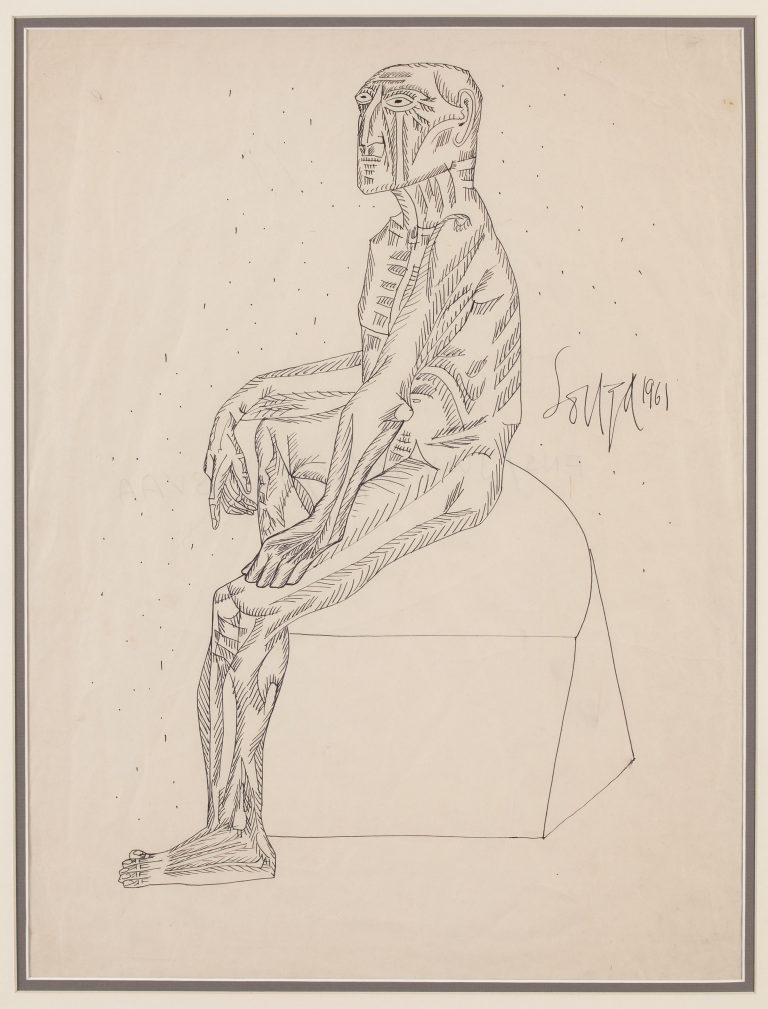

AJ: I am a selective but passionate collector of contemporary art from South Asia. My other deep interest is Chinese porcelain made for Indian and Islamic markets in the 17th and 18th centuries. These are hybrid objects, of course! I try to collect within certain parameters but sometimes break the rules. I am about to acquire a 17th-century Deccani miniature of a youth in a garden that is intoxicatingly beautiful, for instance.

BL: What of contemporary art; are there any specific artists you are keen on?

AJ: The artists featured in ‘Ethereal’, the exhibition I recently curated at Leila

Heller Gallery in New York are of particular interest. They include Rashid Rana,

Rana Begum, Shilpa Gupta, Manish Nai, Noor Ali Chagani, Sonia Khurana, Prem Sahib, Dilip Chobisa, Irfan Hasan, Faiza Butt and Ali Kazim.

BL: Why the shift to an auction house after establishing yourself at the V&A?

AJ: My experience in the public sector was rewarding but by 2007 I was yearning for new horizons. It was also a time when India was emerging as a global economic force, with the formation of private art foundations and the growth of serious collections. I wanted to be involved in this period of growth. Christie’s was keen to have someone on their team that was comfortable both in India and the West and had strong collector and institutional relationships in both. Knowing my commitment both to writing and to public art, Christie’s has permitted me to contribute to such projects, whether working on Maharajas and the Husain exhibitions at the V&A, the book on the Al Thani Collection and subsequent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or participating on the South Asian Acquisition Committee at Tate.

BL: Has working for an auction house has been more freeing than working for a public institution? What would you say are the demands of your role as well as the advantages?

AJ: A business succeeds because it recognises opportunities and seizes them, building new markets and new products. Look, for example, at how Christie’s has helped to take the Indian modern art market to new heights by holding live auctions in Mumbai. So, to answer your question, yes, at Christie’s the possibilities are endless and I work as part of a dynamic and enterprising team to develop business and client strategies. But quite apart from South Asian art, I am a member of Christie’s Chairman’s Office; I have an international remit, which means that I work with clients and collections around the world, resulting in major consignments and sales as well as publications and projects with institutions. Of course, this creates heavy demands on my schedule but keeps my work exciting; no two days are the same!

BL: Could you flesh out for me the difference between a ‘collector’ and a ‘patron’?

AJ: A collector is driven to own works of art normally aiming to form a coherent

or cohesive group. A patron may be a collector but is often more engaged with

supporting artists, creative initiatives and institutions.

BL: Let’s go back to the Maharajas for a moment. According to your research, the highest commission that Cartier has ever received to date is from the Maharaja of Patiala (in 1928). Possibly just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the magnitude of Indian patronage and appreciation of luxury craftsmanship. Would it be correct to say that there is a long tradition of collecting and patronage of art in India?

AJ: India has a highly evolved visual culture, developed over millennia under both sacred and secular patronage. The subcontinent has experienced many high points of artistic creativity.

BL: Why do you think this sense of patronage does not exactly extend further to contemporary art the way it does in China?

AJ: Patronage for contemporary art in India is growing; take for instance

institutions and initiatives created by Feroze Gujral (Outset), Kiran Nadar (Kiran

Nadar Museum of Art), Lekha and Anupam Poddar (Devi Art Foundation) and

Rajshree Pathy (India Design Forum). The Kochi-Muziris Biennale is evidence of the growth of public art philanthropy in the country. It is difficult to compare India with China, whose government has a pro-active cultural policy that includes the regeneration of existing museums and building new ones, strategic lending of exhibitions to institutions around the world and strong support for contemporary art.

BL: We have a new, very proactive government in India today. On their pro-growth agenda is the systemic attempt to do away with petty bureaucracy

and to invigorate tourism and culture (minus the chauvinism, hopefully). As

someone who straddles the best of both worlds, i.e. public institutions/

philanthropy and the auction business, what, in your opinion, are the most

urgent issues that the Modi government could well address?

AJ: There are many ways in which Government could support the arts.

Incentivising collectors and philanthropists by creating a favourable tax environment for imports of heritage objects or for contributions to the arts is

essential. Embracing public partnerships would open up a world of opportunities and would breathe new life into museums in India. Finally, India deserves to be better represented in the international art scene whether at the Venice Biennale or through major Indian-content blockbuster exhibitions shown around the world.

Images courtesy: Christie's Images Ltd. 2015