Titled ‘Caput Mortuum’, one may expect artist Varunika Saraf’s solo show at Chemould Prescott Road to be dark, violent, even gory. Indeed, it was, but walking into the gallery on a clear December morning, one saw intricate art on fabric as light as air, delicate paintings in alluring clusters, including several works that shimmered in the changing light. However, the initial experience of aesthetic playfulness transformed into serious commentary as soon as I stepped closer to the artwork for a conceptual reading of the work at hand.

The exhibition design was comprised of large artworks mingled with smaller series of work, but despite the difference in size, the visual language remained consistent throughout the work. This was an intricate manuscript painting style, in the traditional style of painters in Deccan, Mughal and Rajput courts. It is important to note, that the work possessed not just stylistic similarities, or folio/manuscript-sized artworks, but actual motifs such as the emaciated horse and groom, alongside distinctive renditions of forests that linked the past to the present through their foliage. European medieval imagery from Augsburg Wunderzeichenbuch (Book of Miraculous Signs) appeared in various artworks, here bringing the cosmos—comets and heavenly bodies—into the artworks.

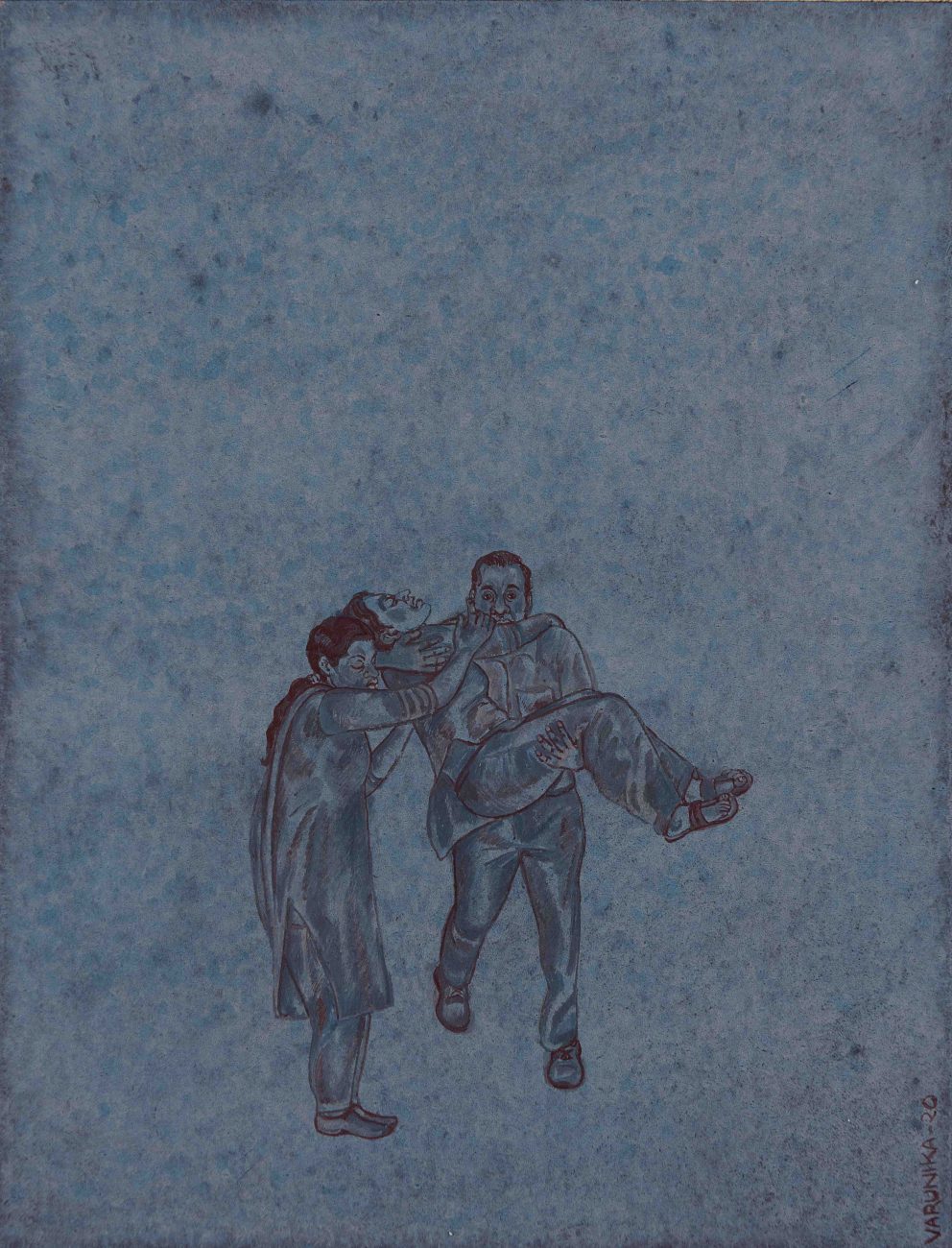

However, no motif is simply transplanted, Saraf superimposes elements from art history with images that surround her now—policemen beating unarmed protestors, for example. At once personal and political, Saraf creates islands and clusters around her works, while speaking up about issues that currently dominate our newspapers, and are in circulation all around us. Literature and criticism is also drawn in, sometimes through quotes accompanying artworks and at other times as references. Caput Mortuum, Miasma and Miniatures are portraits clubbed together with chilling, plain but grainy backgrounds, all reflecting decay, degradation, and depravity of faces inciting violence—portraits of politicians and “leaders” performing hate speeches, and images of police brutality—men, women, protesters being beaten mercilessly. In contrast, Those Who Dream has images of individuals with vibrant backgrounds—mosaic floors that resemble the floors of palaces of Alhambra. Nocturnes is a response to the unfathomable madness, and the nightmares that unfold—the inexplicable but gradual tear in India’s social fabric that we continue to see.

There is a dark sense of humour that comes through in this exhibition also, this is especially apparent in Vikas Band & Co.—a deep blue canvas, with looming mountains and a cluster of images in the centre. Fireworks have been set off above “vikas”, but illuminates nothing whatsoever. A truck decorated with garlands is overflowing with those who promised progress, and have succeeded only to rouse a swashbuckling skeleton, high above in the hills. Is the skeleton armed to protect? Is he fleeing? Viewers can use these visual cues and motifs to come to our own conclusion about these narratives.

Saraf’s practice is an attempt to understand how we, as a society, are here today. This is done so by examining the history of India, in a series of 46 works, titled We, the People. Individually comprising each map with a tie and die technique, where the border looks like stains of dried blood, she embroiders images into the space within the map to retell the story of India. She recount key moments, for instance; the tragedy of Partition, the devastating gas leak; citizen-led movements like the Narmada Bachao Andolan and Chipko movement; loss on account of “development” and more. Each map has a hand-embroidered caption, the name of the photographer and source of the image, with a date. Forty-five maps tell us a story, and the forty-sixth is left blank—the future, hopefully, a future that will be less bleak for all citizens, through this also perhaps here encouraging audiences to take an active level on engagement with polemics and the world around ones self in an effort to stay vigilant to and to avoid the unfolding of future tragic and traumatic events in the future. The blank work is a proposition to us all.

Saraf’s practice itself is a form of social commentary. She uses techniques such as embroidery and smocking, usually dismisses as activities to keep women of leisure occupied. Of course here, the artist is taking on the use of such practices with a feminist awareness and lens. In the series Mood Indigo, a portrait is at the centre of a cloth fragment. Each portrait is that of a woman, seated in various postures—the face looks familiar, perhaps these are self-portraits of a woman artist in contemplation, despair, or frustrated with the state of the world and the constrictions placed on her, here a socio-political tension is played out with viewers.

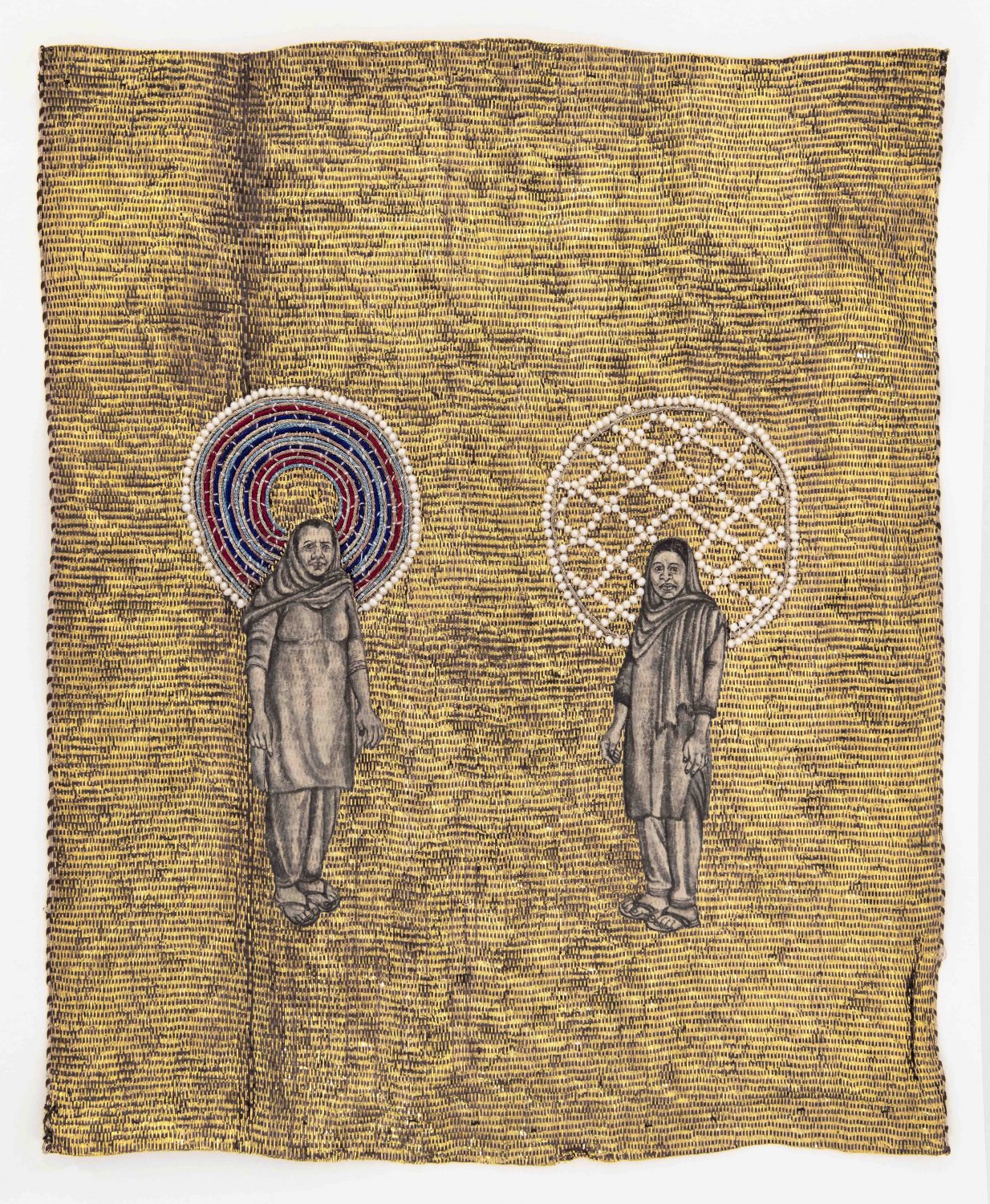

Her fierce feminism shines through the most brightly in a small series of work called Jugni. One can translate the title to spirit or essence of life, or simply rebels and this features women with fierce agency, who protest injustice, and fight for their rights, for identity and partisan politics. The portraits are those from female-led protests, by embellishing them they resemble Madonna imagery from Russia, they turn into icons—which, while benevolent are also full of power and active, rather than items of hollow veneration. Gota—metal threads woven into fabric—is often used in women’s festive wear, especially in a wedding trousseau, and using Gota as the base for portraits, Saraf adds further layers of subversion. Breaking her own necklace to create halos of pearls around the women, she joins countless women who stand up for their cause, those who are not subservient, and refuse to accept the Madonna/whore binary complex. Mixing metaphors with materiality, Saraf’s Jugni is iridescent, and optimistic—women standing up for themselves is the light shining at the end of a very dark tunnel, and provides hope for her community of feminists and those of future generations.

For ‘Caput Mortuum’, Saraf has woven terror with sheer beauty—much like a Mughal artist who has depicted war and destruction with charm, sensitivity, and flawless style. One walked out of the show with a sense of doom, indignant at state-sponsored brutality, lamenting the rip in our social fabric, reflective of one’s silence or protest, but also bedazzled with the intelligence, agility and material choices put forward by the artist—and that is Varunika Saraf’s greatest triumph.

‘Caput Mortuum’, solo show by Varunika Saraf, 25 November–31 December 2021, Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai