This issue of TAKE on Art focuses on the production and circulation of printed books, particularly those devoted to the arts of India. A short list of suitable books in any one genre is fraught with the danger of personal subjectivity. With that as a given, my central premise has been on identifying seminal books across a wide gamut of topics that shed new light on the various disciplines of India’s arts. Seminal means different things to different people. My filter for books is purely an integrity of purpose and the creation and articulation of new bodies of knowledge. Books featured across this issue include those on paintings, botanical drawings, photography, cinema, textiles, design, architecture, ecology, children’s publication, material culture, exhibition catalogues and more; all made public within this new era of the Anthropocene. One limitation is the fact that each of these selected books are in the English language. No disrespect is meant to those books that have been published in regional or foreign languages and not considered. However, there is no escaping the reality that almost all contributors to this issue are most comfortable writing in English and my awareness of Indian art books is of those published in the English language.

India and her arts are central to the selection criteria across this issue. Beyond the typology of categories that books inhabit, another mandate maintained was that the publications identified for review needed to further our understanding of their respective domains. These books thus present us with a multitude of fresh ideas and conceptual frameworks, rigorous and innovative scholarship, design articulation, visual impact, and unique storyboarding techniques. They also look at unexplored and hitherto marginalised aspects of art, larger bodies of related work and nuanced collection analysis. Selected books have been either authored by Indians or by those who work on the arts of India. Furthermore, they were published by a wide array of local and international publishing houses. Many have circulated within niche audiences and have remained practically unknown outside of them. My fervent hope is that this issue will help draw renewed attention on these publications and ensure their presence in any meaningful analysis of books on the arts of the subcontinent from the year 2000.

The history of the book in south Asia is a layered story of multiple languages and scripts that date back more than two millennia. Today most scholars accept that the invention of writing in India dates to 260 BCE (reign of Emperor Asoka) with the creation and use of the Brahmi script for royal promulgations. Brahmi thus became the plinth on which the edifice of almost all Indian languages rest. The story that then comes down to us is mostly a history of the manuscript book in a variety of mediums from birch bark to vellum, talipat, later palmyra palm leaves and copper plate before the arrival of paper in the 15th century. Print culture however reached the subcontinent by the mid 16th century with India’s first printed book in an indigenous language being printed in Tamil. The books discussed here are thus a continuum of this venerable lineage even if their makers didn’t hold this dictum while creating them.

My training as a researcher in early photography was of no help when I confronted the photobook Witness edited by Sanjay Kak. The book’s format, design, layout, binding, and narrative structure besides every other aspect of it questioned accepted wisdom on how books ought to be. That’s what truly makes a seminal publication, an inherent quality to push boundaries and the quiet understanding that nothing is sacrosanct when a story needs to be told. The book is an insightful account of three decades (1986-2016) of Kashmir’s lived history and ongoing political struggles as seen through the lens of nine photographers. These nine individuals lived through these struggles and have captured documentation in searing detail; a narrative in variance to much of India’s perception of the region within a catchphrase of being an idyllic ‘paradise on earth’.

Museum catalogues are usually a compendium of what a collection contains. Textiles and Garments at the Jaipur Court by Rahul Jain is however a first for many reasons. The book conveys the story of not just what the collection now holds but explains in great detail the incredible objects that left the collection in the early 20th century and are now housed in significant repositories worldwide. Together with what remains at Jaipur, this combined pool holds a unique position in the history of textiles of India for its wide range of material types and the early periods that many of them date back to. Jain’s masterful study includes a detailed focus on the Jaipur Court’s system of inventorying and maintaining records of textiles via inscriptions. This approach is an important future direction that one hopes other studies of textile archives will emulate.

The urge of colonial players to endlessly document land, people and the natural world meant that the arts of the botanical sciences with detailed illustrations received significant patronage. While some of this material remains in India, much left India’s shores and reached The Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, United Kingdom where the material was systematically documented and researched on. This has today allowed for superb publications around Indian’s botanical heritage. The two books considered here are The Dapuri Drawing: Alexander Gibson and the Bombay Botanic Gardens and Indian Botanical art: An Illustrated History. While one is a detailed study of a particular garden and the remarkable drawings produced from its holdings, the latter is an overview of the history of Indian botanical art across collections, patrons, and artists. The review thus looks at two publications that are nearly two decades apart and bookend the study of this hitherto lesser known genre that needs greater exposure.

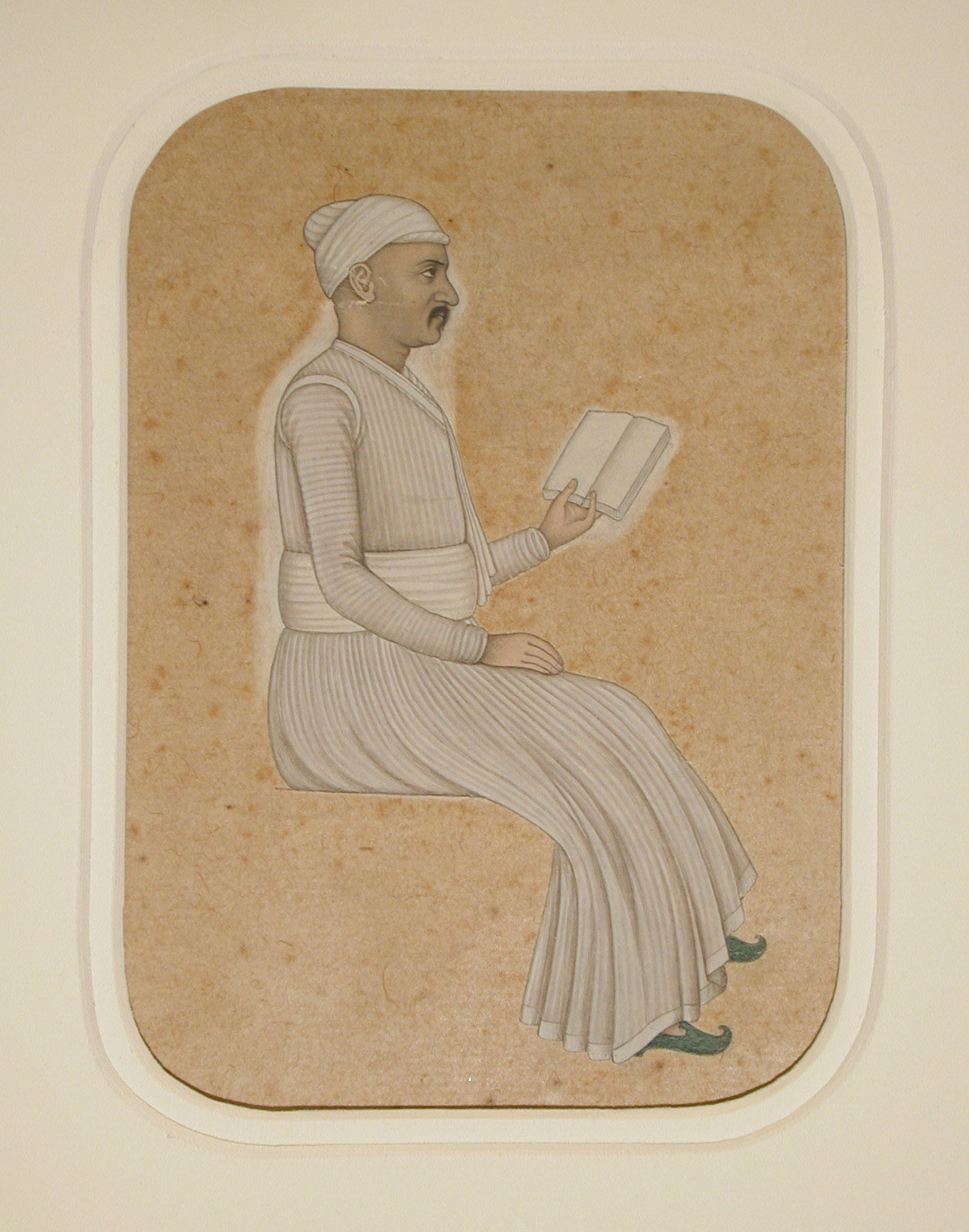

Traditional Indian paintings popularly called miniatures have seen a plethora of publications around their themes, groupings, collections and patrons. However the 2010 publication Intelligence of the Tradition in Rajput Court Painting, moves beyond the usual filters of examining paintings by schools, styles or as exhibition catalogues. The book places rigorous scholarship as its base and moves over and above engaging with just images and includes in its mandate a study of terminologies, relationships in the Mughal-Rajput painting canon, records, inscriptions and accompanying textual analysis. Furthermore, a deep dive into paintings from Mewar allows us a nuanced look at how Rajasthani court artists make the formal choices that characterize their tradition? More than a decade after its publishing, the book’s methodologies and contexts continue to delight readers and it holds a unique position in its innovative study of Indian paintings.

Amidst the splendour of India’s architectural heritage, we often forget that ephemeral architecture has equally been a part of our historic and contemporary fabric. From tented structures to shanty tin sheds across much of India, the transitory nature of dwellings is a living reality. The Kumbh Mela of 2013 at Allahabad/Prayagraj which I attended was one such site that captured the question of living within temporary cities. Kumbh Mela: Mapping the Ephemeral City, edited by Rahul Mehrotra and Felipe Vera admirably captured this phenomenon through a series of visual and ual essays. The book is a crucial addition in the discourse on urban planning in India and has the rare quality of being able to weigh in on the importance of matching modern city planning disciplines with age old methods without looking at the two as opposing each other.

The 21st century has seen the arrival of the graphic novels as an important genre of storytelling, dissemination and publication in India. Amidst the various titles that populate this section in bookstores, one title stands apart. Bhimayana, Experiences of Untouchability, Incidents in the life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar with art by Durgabai Vyam, Subhash Vyam and text by Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand. Amidst the several narratives that the book has been credited with, one that particularly appeals to me is the reimagining of Ambedkar’s life in the format of an Indian historic (Itihasa) epic beginning with the addition of ‘yana’ as a suffix to its title. The inspired use of Pradhan-Gond art and artists, along with the narrative choice of intertwining past events with present incidents give the book remarkable vitality while creating a unique graphic biography. The review here examines Bhimayana within its physical and social dimensions and through the context of three filters – anti-caste communications, art, and a query on the afterlife of the stories it presents.

Over the years a stellar collection of publications tells us the story of Indian art, modernism, and its evolving journey. The books in question here are In Medias Res: Inside Nalini Malani’s Shadow Plays by Mieke Bal and 20th Century Indian Art: Modern, Post- Independence, Contemporary, edited by Partha Mitter, Parul Dave Mukherjee and Rakhee Balram. The two books reviewed are opposites; in that while the first dialogues with the creative output of a particular artist, the second is an exploration of the larger field including the said artist, while explaining the prevailing scholarship around art history in 20th century India. The selection of these books was intentional to showcase how micro and macro histories of art are produced and why a reader needs to engage with a myriad narratives to truly appreciate and engage with the corpus as whole. While the former looks at cultural theory through a single artist’s work, the latter is almost encyclopaedic in its scope. As unilateral perspectives increasingly becoming the norm, these books articulate how individual histories are valid ways of studying art practices as against the notion of a prescriptive universal canon.

Over the years a single independent publishing house (Tulika Books) seems to be focusing on fundamental books that expand our knowledge of Indian cinema amongst a host of other titles on their roster. Of the several books on cinema they published, our focus is on Project Cinema City edited by Madhusree Dutta, Rohan Shivkumar and Kaushik Bhaumik. The book examines the ubiquitous place of cinema in Bombay and visualises the city as a ‘living archive’ across its surfaces, public and private spaces, in permanent and ephemeral memories and across every unchartered territory that profess to being its turf. The book was accompanied by an eponymous exhibition that was seen in multiple Indian cities and overseas. It publication’s seminal idea as explained in its forward is its ability to showcase ‘an artistic practice that transforms existing works into new ones without either plagiarism or irony’.

Every time I look for material on the Indo-Islamic heritage of Punjab one name that constantly comes up is that of Subhash Parihar. Besides being the head of a department of history in a government college in Punjab, he has to his credit numerous books, more than three dozen research papers across international journals, all of this done while fulfilling his day job as a teacher and art historian. His documentation and photographs of the region’s paintings and sculptures are possibly the greatest repository of visuals that illustrate Punjab’s layered built heritage. While ostensibly a review of three of his major books that tackle Punjab’s Mughal heritage, out attempt here is to single out a scholar who by himself has become a byword for intensive study albeit remaining unknown beyond a small group of specialists. The books considered here are Islamic Architecture of Punjab (1206-1707), followed by Land transport in Mughal India, Agra-Lahore Mughal Highway and its Architectural Remains, and History and Architectural remains of Sirhind: The Greatest Mughal City on Delhi-Lahore Highway.

One of my struggles over the last few years has been to find a truly original book on Indian design that went over and above beautiful images, descriptive captions, and lush layouts. True design to me is a philosophy, something that engages with the given material at a fundamental level in its materiality, its construction, outward form, and the service it hopes to perform. The only story that met all these parameters and more was With Great Truth & Regard: The Story of the Typewriter in India. Ironically the book details the design history of an outdated machine the Indian typewriter as produced by Godrej. The fact that the book goes beyond one brand and examines the larger field of other typewriters is a major plus. In the end what really adds to the project is not just the fascinating textual content in the book, but a story of design choices and of various layout formats designed to perfection by an inspired designer Sarita Sundar.

Alongside the books detailed above, this issue of TAKE on Art also includes shorter reviews of other volumes that are significant in expanding our understanding of the arts in India. These include publications on maps, topographic and urban city studies, children’s publications, ceramic arts, and exhibition catalogues. This final category needed to satisfy a major criterion of being more than just the story of a group of objects and needed to expose the larger history of a genre. A much longer list also exists of publications that did not make it to this issue. Several of them were in the reckoning and were finally abandoned for one reason or the other, but mostly for the practicalities of making the deadlines needed to complete this issue. No list of favourite books can possibly include every critical volume produced. By the means of this issue, we hope to be able to challenge those who work and create publications on Indian art to consider what is it that they add beyond reams of paper, printed images, and clever layouts. Do the tomes we produce significantly add to the field we represent or are they a rehashing of old ideas or vanity projects? The books represented here are the best of what has come out on India in what is nearly the first quarter of the 21st century. New perspectives are often unchartered territories and that’s what these books offer. Those of us who make books and read them must necessarily traverse this path to ensure a sustained and questioning vitality in our engagement with the arts. That single minded pursuit of integrity is what makes books worth reading.