The retrospective on Bangladeshi photographer-writer-curator-activist Shahidul Alam, ‘Singed But Not Burnt’ provided a rare opportunity to appreciate the artist’s diverse oeuvre. Curated by Ina Puri and exhibited at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity from 19 June to 20 August 2022, it looked at Alam’s artistic genealogy, wide-ranging creative style and visual politics in the context of the shifting terrain of contemporary lens-based practices in South Asia. The show’s narrative thread flowed in an autobiographical voice interwoven with the biography of the postcolonial nation-state of Bangladesh—a land torn between democratic values and counter-democratic realities, majoritarian identity and minority rights, the exploitation of labour and efforts at social empowerment, complaisance to power and resistance against it. In bearing witness to the historical and the everyday, Alam continuously blurs the boundaries between the aesthetic, the political and the personal. Simultaneously, the retrospective showcased Alam’s critique of the Global South’s erasure from the history of photography and how his prominent presence in the “West” is a corrective towards decolonizing photography.

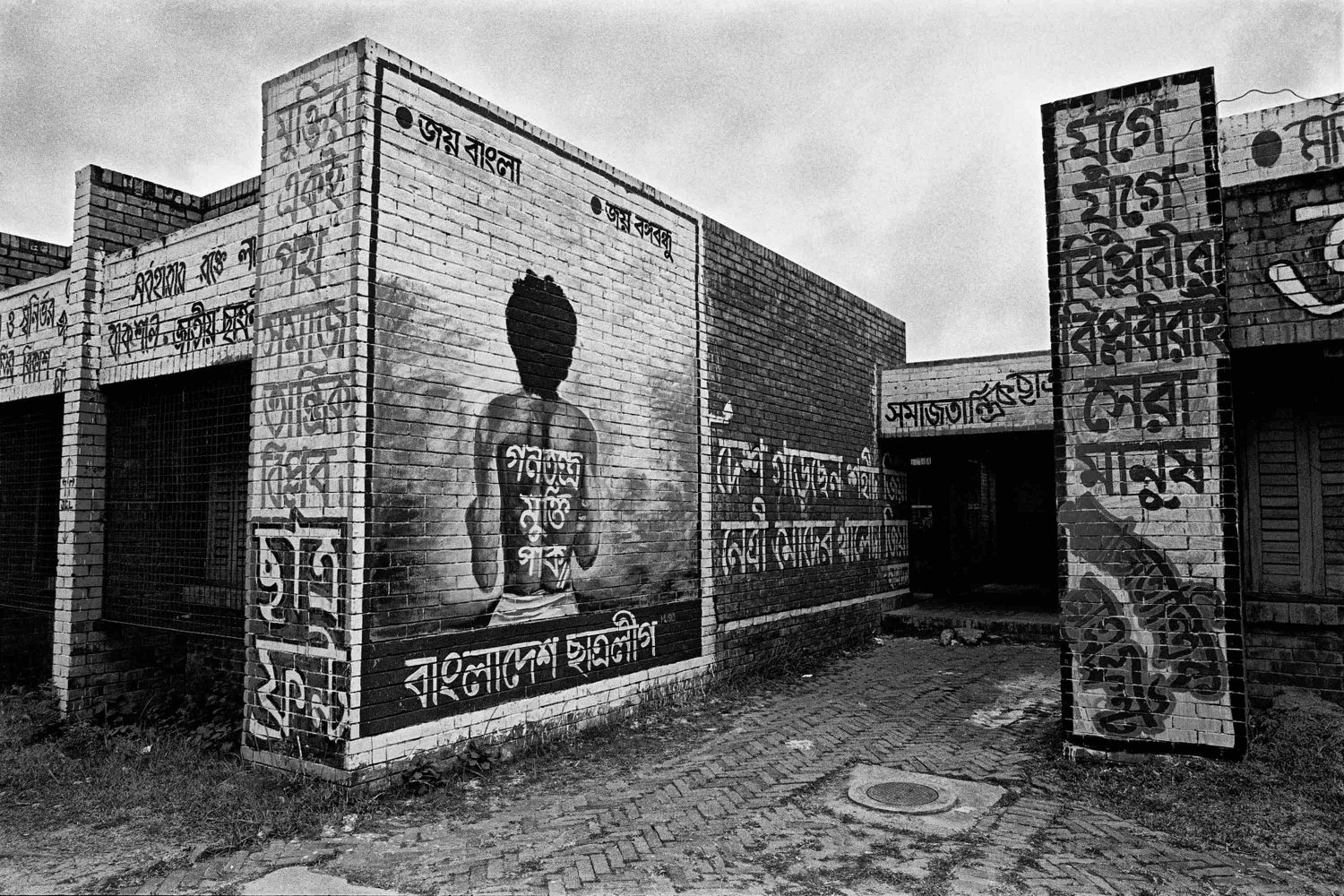

Visitors to his exhibition might have been familiar with Alam’s politics of the streets, his black-and-white documentary photographs and his contributions as an institution builder through Drik, Majority World, Pathshala, and Chobi Mela. These endeavours occupied substantial sections of the show. They included Alam’s much-reproduced photographs of the mural at the Jahangirnagar University campus honouring Noor Hossain, a student killed in police firing in 1987, who wrote ‘let democracy be free’ on his chest (Figure 01) to protest the dictatorial Ershad government, and the silhouette of a woman in a voting booth in 1991 who (in Alam’s interpretation) cast her ballot to avenge Hossain’s murder (Figure 02). The more unusual exhibits were Alam’s early experiments with infrared photography in England and Bangladesh within the ambit of salon photography. Viewers must have been pleasantly surprised by his nude self-portrait, which recalls British cultural theorist John Berger’s expose on the genre of the nude and Alam’s challenge to the genre. However, what Alam calls his pictorialist “pretty pictures” appear, in hindsight, as political as his larger body of documentary works.

Two sections in the show demand longer discussion: Crossfire and My Unseen Sister. In the former, Alam’s visual language takes novel formal, chromatic and conceptual turns. Six of his constructed colour images (Figure 03), made between 2009 and 2010, were showcased, reflecting the horrors of Bangladeshi citizens killed in extrajudicial “crossfire” by the government’s Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) set up in 2004. Alam realised that his well-honed monochrome documentary style would be insufficient for telling the truth about these unaccounted deaths and disappearances. As an alternative, he reconstructs the scenes with objects and stories associated with the victims. While more details on the processes of construction would help to think through his aesthetic choice, the sites, objects, composition, and dramatic light demonstrate how his act of imaging is a form of resistance when ‘[t]he culture of fear …has crept into Bangladeshi psyche….’ Despite their formal affinities with Alam’s early experimentations in pictorialism, these “constructed” images appear politically closer to his “documentary” practices, which have been his weapons of protest against state violence.

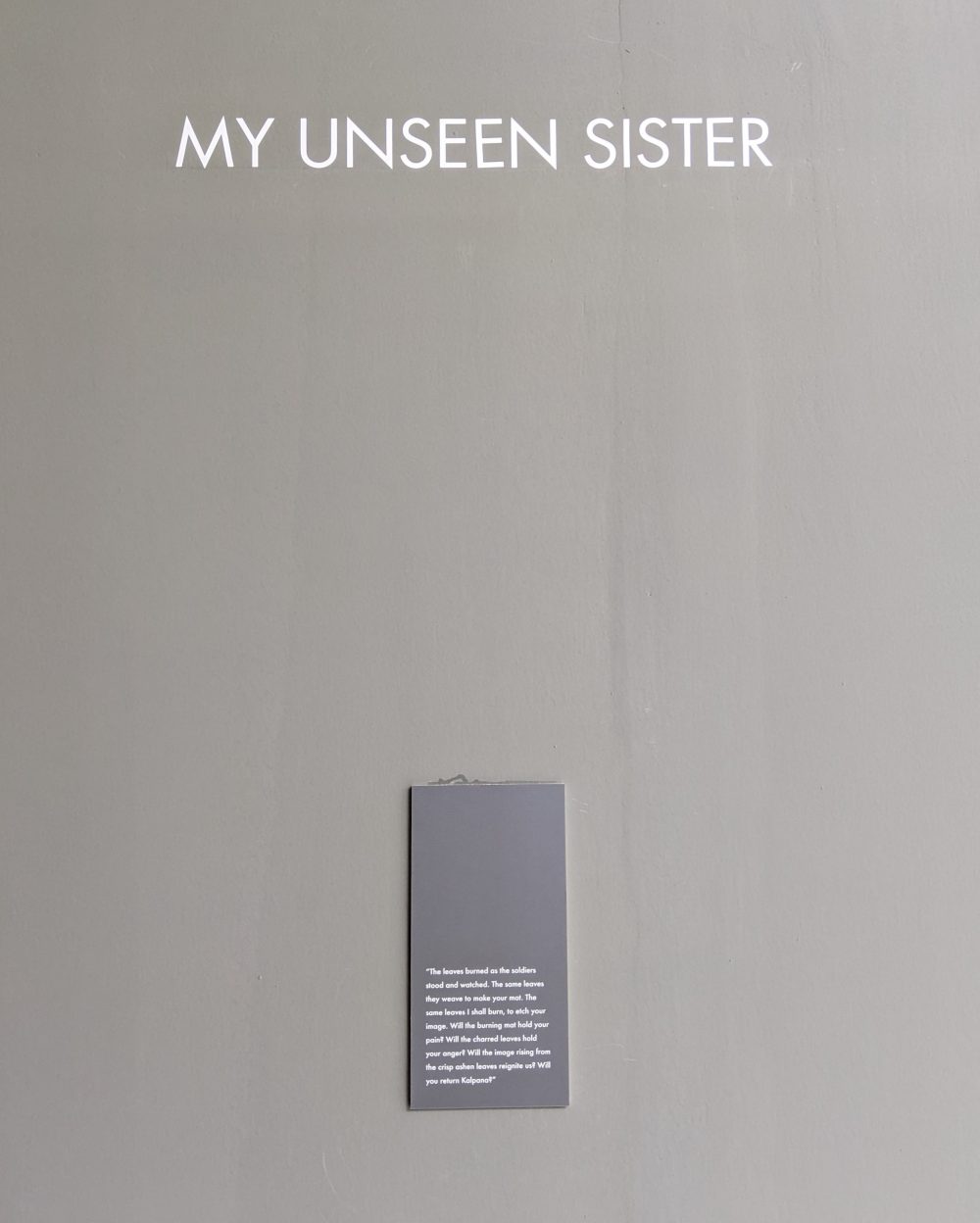

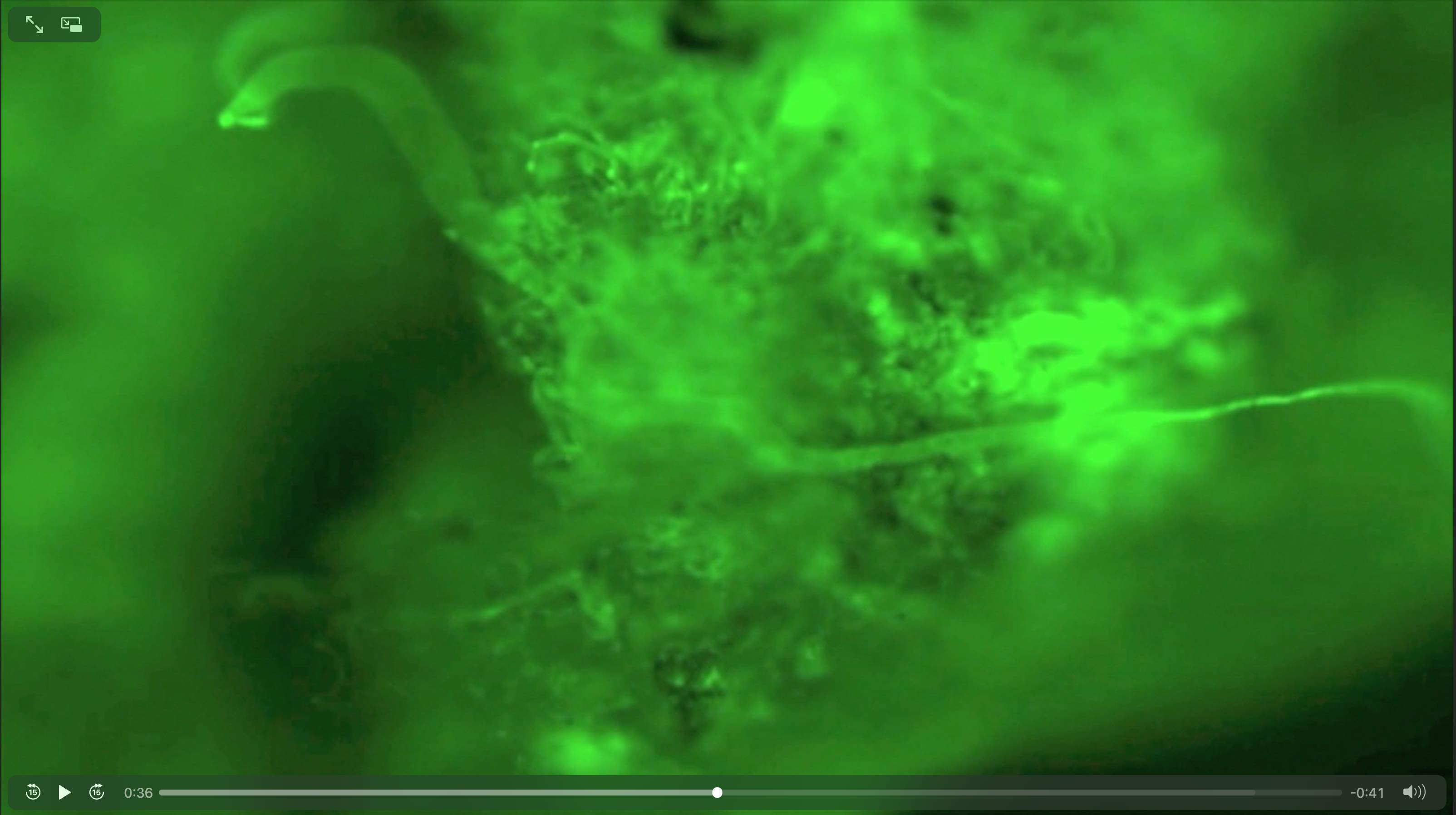

The conceptual turn in Alam’s work is at its finest in My Unseen Sister, which resides at the intersection of politics, aesthetics and technology. ‘Will you return Kalpana?’ This was the polemical ending to the ode introducing the section, unintentionally displayed as if it was signage to a seemingly missing artwork (Figure 04). The blank space between the section title and the printed words underneath mimicked the absence of protagonist Kalpana Chakma, who went ‘missing’, leaving behind only ephemeral physical traces. Hailing from an ethnic minority community, the Bangladeshi rights defender was allegedly abducted from her home by the army before the general elections of 1996, and never returned. What remains are Alam’s photographic traces of Chakma’s left-behind shoe and a book on Lenin from her bookshelf. This absent presence is also palpable in Kalpana’s Mat 1-8 (2015), an installation with photo portraits of eight human-rights activists, laser-etched on straw mats, and accompanied by a 2-minute 40-second video loop of a tree bark filtered through fluorescence microscopic cell imaging (Figure 05) to augment Chakma’s narrative trace. My Unseen Sister comes as a jolt to viewers as they try to grasp the historical context of her disappearance and object-images that reduced her to their constitutive elements. Indeed, the “optical unconscious” in the video poignantly unearths the information apparently missing in photographs addressing a missing individual. Human and natural histories collapse in Alam’s commentary on state violence perpetrated on the intertwined lives of ethnic minorities and the natural environment. This is foregrounded in the 40 x 27 inch print of Kaptai Lake (2015) as a site of marginalisation in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, the homeland of the Chakma and other ethnic and linguistic minorities. The accompanying text reminded viewers of how the artificial lake inundated the tropical rainforest and the palace of a tribal king. Together the mats, the video, and the photograph of Kaptai, hauntingly demonstrated Alam’s lifelong commitment to voicing “truth to power.”

‘Singed But Not Burnt’, Solo show of Shahidul Alam, Curated by Ina Puri, Emami Art, Kolkata, 19 June–20 August, 2022.