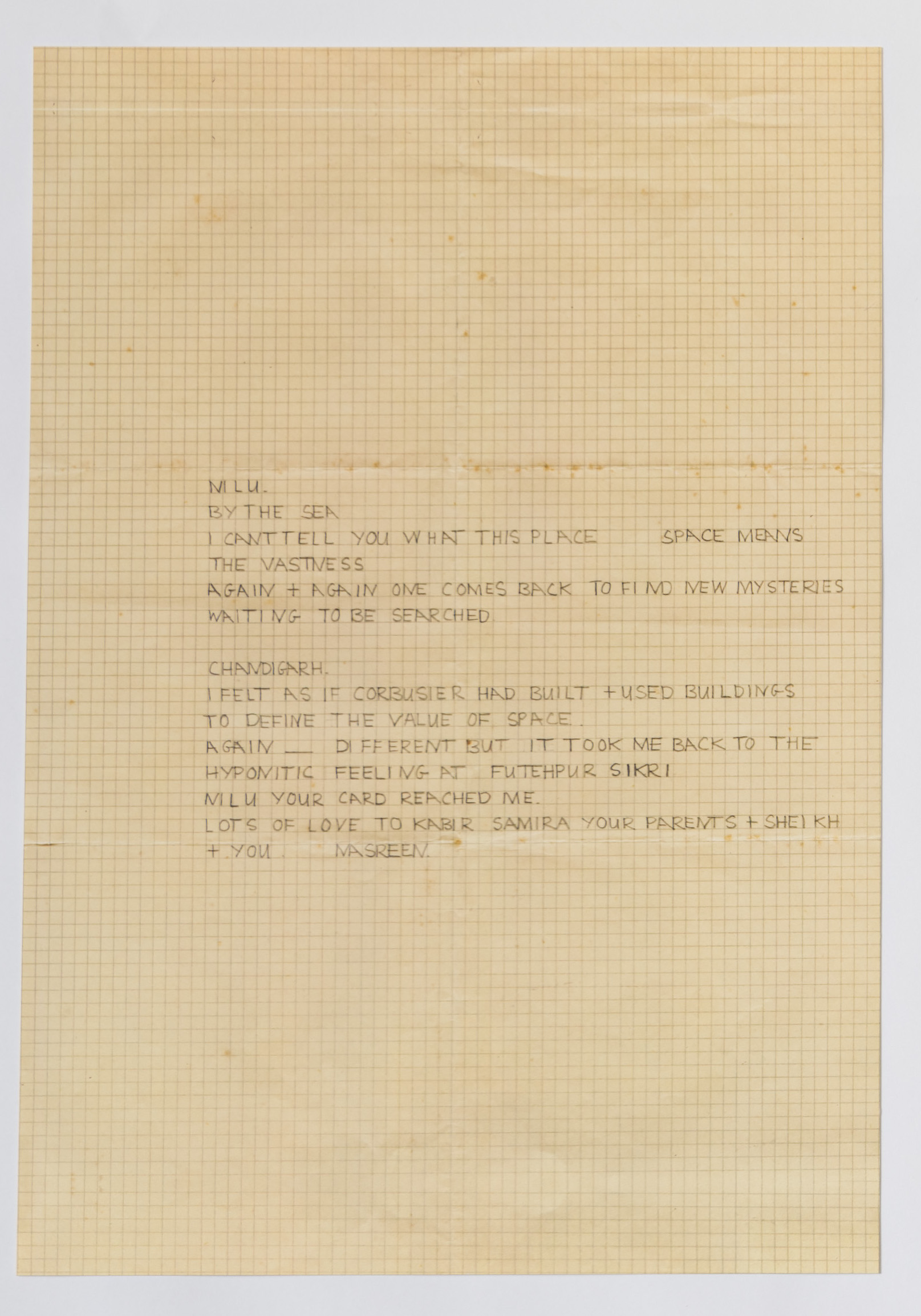

Nasreen Mohamedi’s letter to artist, Nilima Sheikh, Image Courtesy: Nilima Sheikh and Asia Art Archive.

Nasreen Mohamedi’s hand-written letter to her close friend, artist Nilima Sheikh exudes a sense of both restraint and tenderness. With her formal handwriting, she composes what appears as a verse of concrete poetry – simultaneously referencing and exploring ideas of space – on a piece of graph paper. Providing a window into the late Modernist’s preoccupations with nature, abstraction, and the limits of perception, this letter, describing the seashore at Kihim, also inspires the title of her latest retrospective at Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation (JNAF) – Nasreen Mohamedi: The Vastness, Again and Again.

Born in 1937 into a progressive Muslim family in Karachi, and raised in Bombay (present-day Mumbai), Mohamedi is recognised for her minimalist drawings in ink and graphite, calibrating rhythmic lines of different dimensions and weights. Highly controlled and rigorous in her commitment to precision, she laboured over these even through her final decade, while battling a degenerative neuro-muscular condition that she succumbed to in 1990. Her artworks have been exhibited globally since, but this is her first retrospective in her hometown in over three decades. Curated by Puja Vaish (Director, JNAF) it surveys Mohamedi’s art works along with photographs, sketches, archival materials including rare footage, and memorabilia such as her letter to Sheikh. Several of these are exhibited publicly for the first time.

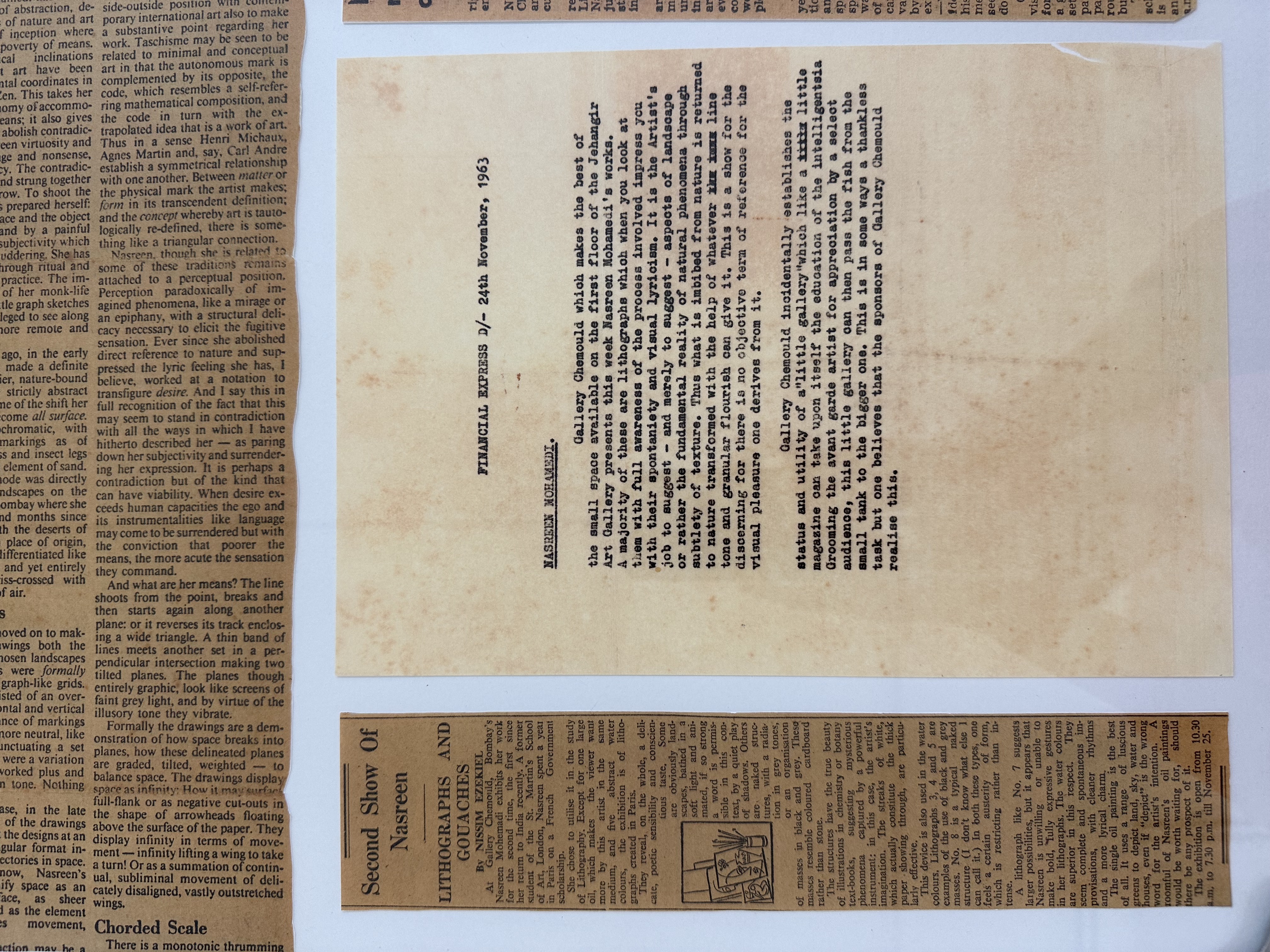

Press clippings found at Nasreen Mohamedi’s Baroda studio, Image Courtesy: Sikander & Hydari Family Archives

Most of Mohamedi’s artworks remain untitled and undated, and while it is possible to trace larger shifts in her practice, Vaish adopts a semi-anachronic curatorial strategy, framing “lines of sight” to trace her visual thinking across diverse media, processes, and importantly, artistic communities of her time. This helps tie her non-referential vocabulary to contexts she was exposed to, and embedded in.

Mohamedi studied at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London (1954–57), and at Monsieur Guillard’s Atelier in Paris (1961-63), eventually returning to work in Bombay and Delhi. At JNAF, her early paintings, Japanese ink drawings and collages, rendered in fluid styles challenge conceptions of all her works being rigidly linear. These expressionist compositions recall European Abstractionists Mohamedi was drawn to, from Paul Klee, to Agnes Martin, and Kazimir Malevich. Yet they are also grounded in her interest in transforming natural and built landscapes into abstract forms – evident throughout her practice.

Mohamedi’s sketches, and journal entries – quoted prominently at the exhibition – reflect on travels to Turkey, Iran, Bahrain, Fatehpur Sikri and Corbusier’s Chandigarh, as well as record mundane observations. Her father ran a photographic equipment business which enabled her easy access to the camera that she used as an exploratory device. Through unconventional crops, angles, and hand-drawn studies, she examined forces of wind and sea, effects of bleaching afternoon light and in some instances, images of frames within frames. Describing Mohamedi’s vocabulary that also resonates with her later works on display, Vaish writes in her curatorial note, “Patterns emerge from light gradations and soft shadows, from the “filigree in water”, designs moulded by the sea, the traces of miniscule patterns in sand by scurrying crabs, the gradual dissolution of ice, or how the geometry of a spider’s web catches the light and reveals itself.”

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, ca. early 1960s, ink and wash on paper, 14 x 10.75 in, Image Courtesy: Dossal Family.

The austerity of her works has constructed an auratic image of Mohamedi as a lone figure. Her practice was singular in light of art movements of her time, which employed figurative techniques or explicitly referenced socio-political concerns, and Vaish also recalls a conversation with artist Nalini Malani who expressed how even as a woman artist, Mohamedi resisted being “vernacularised as female.” Demystifying perceptions of Mohamedi as a solitary personality, Vaish features objects showcasing her engagements with artists in Bombay and Baroda. For instance, we see an ink drawing by sculptor Pilloo Pochkanwala – who also resisted gender-based classification – that echoes Mohamedi’s early arboreal style.

Photographs on display further highlight Mohamedi’s presence at the Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute, a cultural hub, between the 1950s – 1960s where she met MF Husain, Ebrahim Alkazi, Krishen Khanna, Tyeb Mehta, and VS Gaitonde, among others. The latter became her mentor, and the exhibition includes one of his works in proximity to an oil painting by Mohamedi. Portraying similar watery compositions, these capture both artists’ interests in Zen Buddhism and non-representational styles. Mohamedi also participated in the Vision and Exchange Workshop (VIEW) in Bombay set up in 1969, where she notably shared a darkroom with Malani, whose photogram, Untitled III (1970) features next to a vitrine containing photographs, photograms, stencils and film found in Mohamedi’s studio in Baroda.

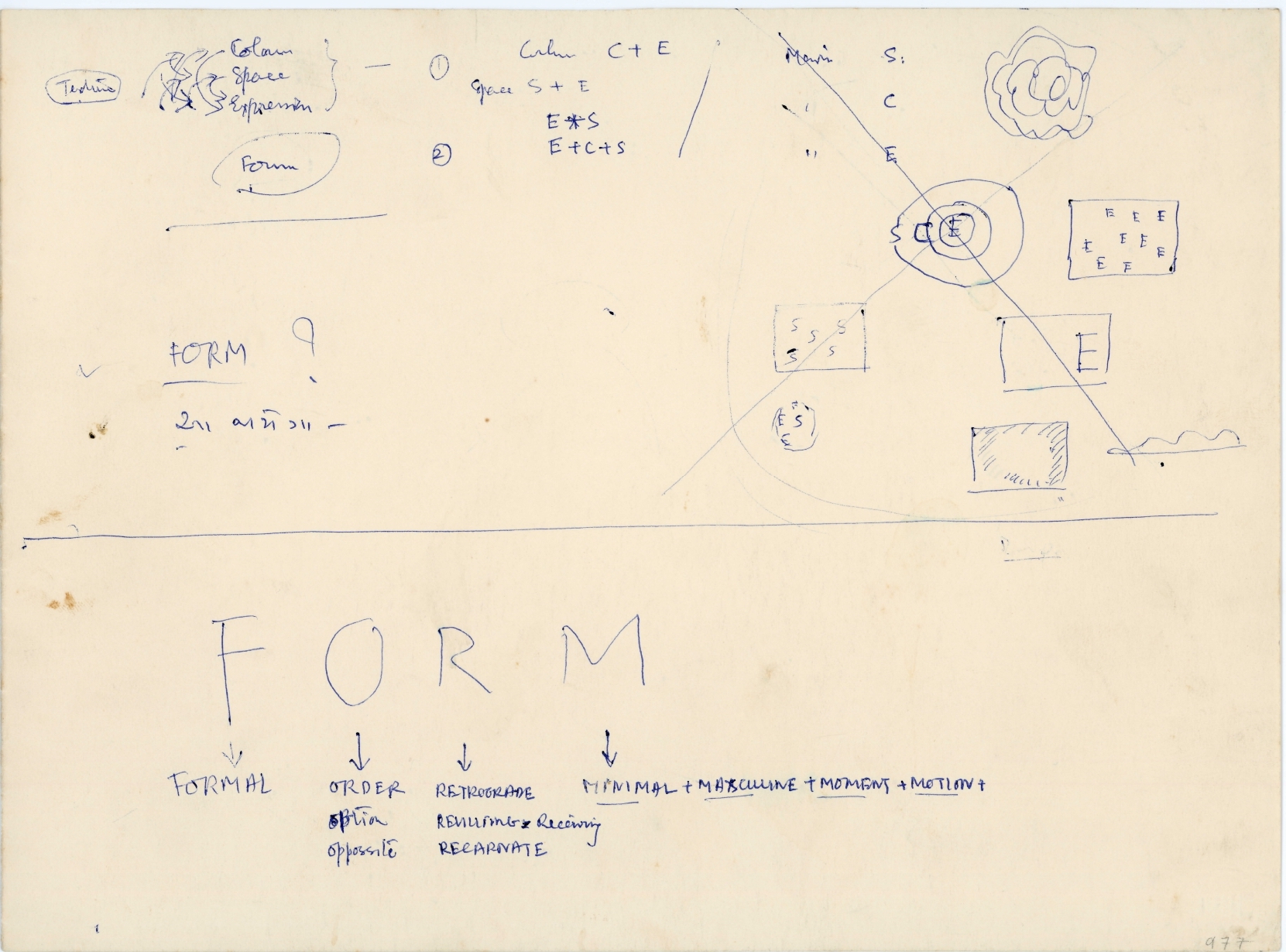

Note found in Nasreen Mohamedi’s Baroda studio, Image Courtesy: Sikander & Hydari family archives.

At the Faculty of Fine Arts, MSU Baroda, where she began teaching in 1972, Mohamedi’s pursuit of purity and unity led to an exclusively monochromatic palette, and greater exactitude, with ever-shifting planes, receding perspectives and elevated forms. Materials from her studio reveal explorations of Arabic typography, her inclusion in a cover of Bhupen Khakhar and Gulammohamed Sheikh’s socially-engaged, art publication, ‘Vrishchik,’ and camaraderie with friends, colleagues and students such as Jeram Patel and Jyoti Bhatt, among others.

Mohamedi’s intricate, highly-formalist works invite intimate engagements, whether or not we know her biography or background. Through this sensitively-curated exhibition, Vaish raises crucial questions about how we might approach her practice and its cultural and art historical context, once we do.

Nasreen Mohamedi: The Vastness, Again and Again, curated by Puja Vaish, Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, 31 January – 28 May, 2023.

#NasreenMohamedi:SingularityandSociability #NasreenMohamedi, #PujaVaish, #JehangirNicholsonArtFoundation, #artreview #takeonart #takewriting #takecurator #artcurator #artwriting #artcritics #artpublications #curatorialwriting #artcriticism #arthistories #artdiscousre #artcollaboration #artcreatives #artcommunities #arthistory #criticaldiscourse