The name of the project includes the term ‘lab,’ emphasising the experimental processes and unforeseen results it anchors. It not only creates a space to practise and produce art but also opens up a space for interaction, dialogue, experimentation, and collaboration. The interdisciplinary nature of the curated programme aims to blur the boundaries between different disciplines in an effort to underscore the idea that the process is the practice. The artwork is not the final culmination of results achieved during laboratory experiments but remains porous enough to continually add meaning. The incubation of ideas is underlined over the final shape and form of the artwork, where the artists’ responses to the city set the framework for the artwork.

“The conventional, clinical, sanitised lab that conducts ‘research on’ subjects is reconfigured as an alchemical space that carries out ‘research with’ the city and its citizens. Hence, the project positions contemporary artistic research as an important methodology to map the city by navigating its creative and cerebral topography. The rational clustering of the city that claims to represent it is always rooted in omissions and absences; it only highlights infrastructural layouts, zones, and geographical coordinates. KKCL attempts to map the various aspects of the city by positioning bodies’ responses to spatial patterning, tracing the body’s experience of urban daily life and the urban voyager’s negotiations with the layers of history, memory, and mutating contemporary built spaces,” says Premjish Achari. The residency hosts eight fellows: Atul Bhalla, Leef Werk (an artist collective), Parvez, Radhika Agarwala, Shalina Vichitra, Sibdas Sengupta, Sumatra Sengupta, and Vasudha Thozhur. Each fellow has undertaken research that aims to create a parallel between archival knowledge and contemporary cultural practices.

Radhika Agarwala’s research on human behaviour and the biotic elements of the city further supports the concept of the lab. By examining the timeline of structures in the city, she observes an overwhelming growth of algae on dilapidated buildings in her work ‘Travelling Through Time I’. The free-form nature of algae allows it to spread and move as desired, breaking free from the constraints of concrete. Agarwala, drawing on her experience in her home city Kolkata, parallels this growth with the city itself: both organic and inorganic elements thrive at their own pace. This comparison extends to the people who, like Kolkata, live, migrate, and assimilate at different junctures of human history. Agarwala states, “For me, Kolkata has always appeared as a living museum, with inorganic and organic material walking, breathing, and co-existing together—ancient architecture weaving with dancing banyan roots and ecosystems growing within fragmented concrete.” Through a live sculpture—a tree in a controlled yet suitable environment—Agarwala represents a continuous process of growth. It also serves as a repository for the colonial past of the city, depicted through the moss that has grown on colonial structures, bearing witness to its history. The concept of live sculpture also diversifies the scope of how we view the biotic and abiotic elements of the city, anchoring how Kolkata appears to embody a living museum.

Diversifying art practice and the scope of research, the Swiss-based artist collective Leef Werk, run by Neils Coppens and Roman Luterbacher, has developed a public art project, ‘Publics Content Bureau’. Inspired by the concept of Adda—an informal setting for fluid conversations on political news, social changes, and cultural settings, a highly popular site on the streets of Kolkata—they built a makeshift panel that was installed in different corners of the city at various times during their residency. Pedestrians were invited to have conversations about everyday life in Kolkata. Key words from these conversations were written on the black panel, eventually lending a visual language to the artwork. The horizontal black panel, ‘17.11.2023 – 26.11.2023’ , with words written in Bengali, Hindi, and English, calls for the concerns of the city’s citizens. Interestingly, as a collective from the Global North, the interactive art exercise became a learning tool for understanding economic inequality and social disparity. The artwork deflates the idea of global citizenship when the Eastern side of the globe remains in the clutches of poverty.

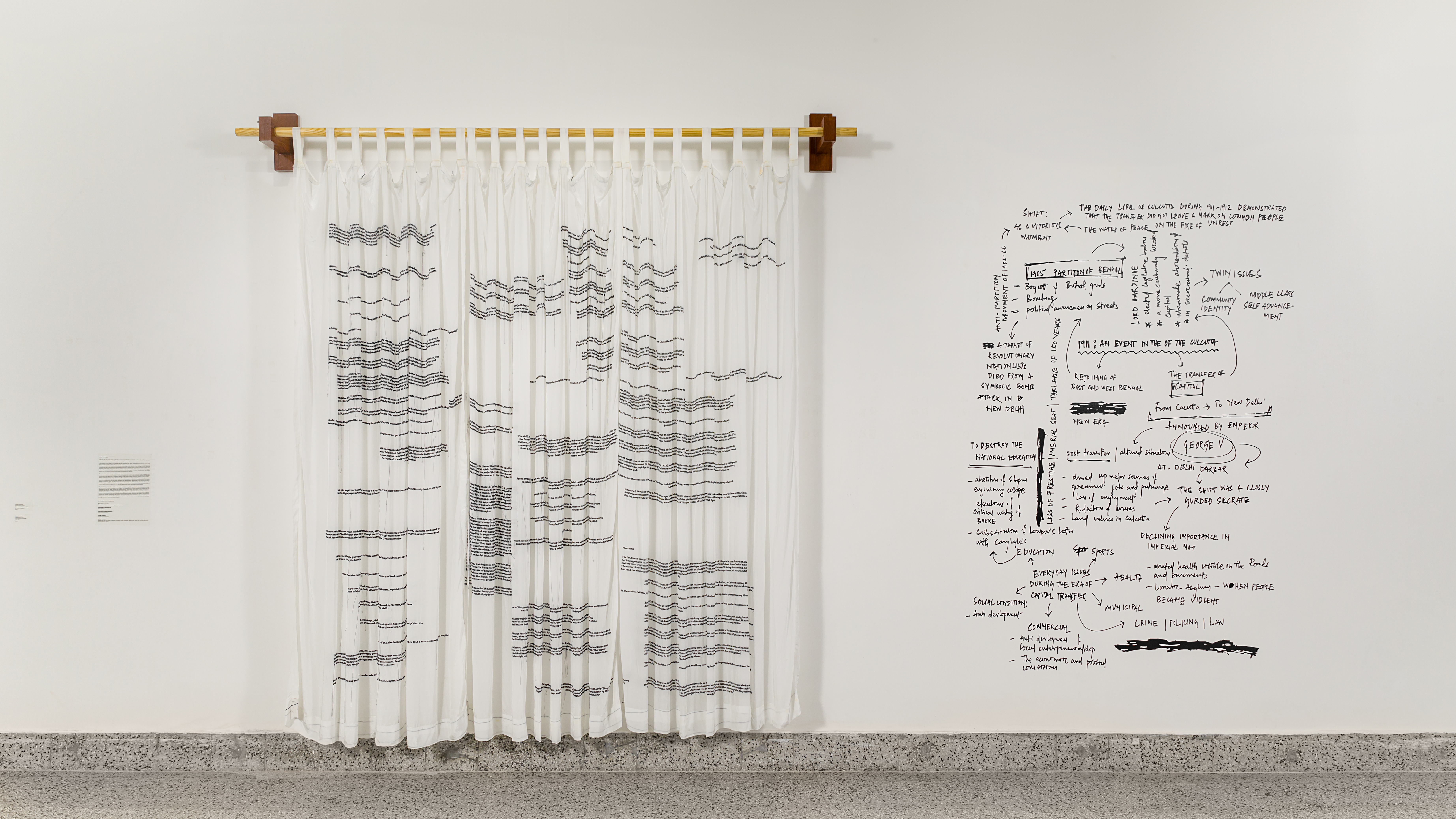

Sibdas Sengupta through his textile work, ‘Translucency of 1911’ creates an archive from the government records, official statements of rulers and governing authorities tracing the event of shifting of the capital of colonial India. The shift of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi in 1911 has been marginalised, bearing direct repercussions on the daily lives of people in Calcutta. Sibdas says, “The events of 1911 and the shift of the capital almost act as an invisible space, almost like a hidden history, which has disappeared from the historical and social consciousness of the city.” Sengupta, treats these archives as ‘found objects’ in order to maintain the ordeal of the historic event that had a significant impact on the lives of people in Kolkata. The lacuna within the history for the event of 1911 is visually translated through the suspension of textile work. The play of shadow and light, along with the textural finesse of the fabric, becomes a metaphor for documenting the event in tangible form as he allows the visitors to touch and feel the fabric.

Researching preconceived ideas and working toward an outcome are characteristics of a laboratory. While pursuing an idea, the result is anticipated and may not lead to the desired outcome. Therefore, the result of Parvez’s video art, ‘A Portrait’ became a reflection of experiments and experiences during his time in the city. Parvez, whose research is based on food practices around the city, focuses on the culinary culture of the region, specifically associated with the daily wagers. Over the course of his research, he develops a self-critique of documenting the labour class, approaching them with a camera, which has been termed a tool of power. On his visit to the flower market, the omnipresence of heads carrying loads leads to a critical reflection on how food and labour have been perceived within the prism of the “bhadralok” or upper class—a certain class of people who have access to food and romanticise local cuisine, while neglecting the labour class’s struggles for food due to their economic conditions.

Kolkata City Lab differs from traditional academia as it does not restrict itself to documentation but instead goes beyond, producing accessible art for the general masses. The project does not confine itself to a controlled and isolated environment but opens up to the people, traditions, art, architecture, and food practices. Premjish Achari approaches the project as a playground for artists to explore the diversity of the city through visual arts. The outcome of the project is not predefined but rather inclined toward the impromptu results of artistic research, discourse, and approach.