Navigating through the gallery space of the Kolkata Centre for Creativity (KCC), Kolkata, was overwhelming for visitors as around 100 odd artworks of Gobardhan Ash (1907-1996) emerged slowly as visceral experiences around them. The Gobardhan Ash Retrospective Exhibition (1929-1969), archived and documented by Princeps, curated by Brijeswari Kumari Gohil and Harsharan Baksh and housed by the KCC, displayed Ash’s artworks that came out of the most creative four decades of the artist’s life. The artworks were supported by a well-organised timeline (across an entire wall) to help the viewer understand Ash’s growth as an art practitioner as he journeyed across forms, locales and institutions. A recluse, Ash’s creative life required a mapping like this to place the viewer in the vibrant years when Ash was learning, sketching, painting, collaborating with other artists, heading departments, trying hard to respond to the social situations around him, being showcased and honoured with awards and recognitions. Such a timeline helps the viewer place the vast display of Ash’s artworks in multiple mediums,

tonal variations, textures and thematic explorations as his evolution as an artist. Ash lived as a responsive artist through the tumultuous times in the history of the nation, from its late colonial era to its young post- independence dreams and disillusionments. A timeline with biographical details provides a context to engage with the life and times of the artist, his sensibilities and ideologies. In this retrospective show, one can stand in front of an artist, fulfilled in his solitude, traversing the path of artistic enlightenment as a lone seeker, while his visions on art remained politically grounded. His ideological and artistic quests brought him close to the artistic fraternity of his times. He also grew as part of artists’ collectives. Ash played a pivotal role in the foundation of the Young Artists’ Union (1931) and the Art Rebel Centre (ARC, 1933) in Kolkata where painters with similar artistic sensibilities and social concerns assembled. All of them agreed on one aspect —they wanted to distinguish the modernistic tenets and sensibilities of the Indian visual arts from that of their western counterparts.

As a modernist coming out of a Kolkata-centric (then Calcutta) circle, Ash makes it beguilingly tough to define his art. Ash came into his own by moving away from the prevalent institutions and styles. It started with his refusal to align himself with the British form of academic art and pedagogical training. He didn’t shy away from expressing his unease regarding these while studying at the Government College of Art in the 1930s. He did not carry forward the legacy of the Bengal School of Art that drew its stylistic devices and emotive play of themes in a revivalist nationalistic imagination. His artistic modernism was different from his contemporaries belonging to the Santiniketan school as well. Stylistic polyvalences made him unique as a modernist maestro of forms while his art remained embedded in a politically vested socialist realism. Yet, his politics did not arraign his oeuvre along a defined political path which artists like Chittaprosad, a member of the Communist Party, intended. Ash’s art, like the art of many of his Calcutta contemporaries, was situated in the quintessential attributes of the 1940s and the 50s, without nostalgia for the past or romanticism for the future. The immediate locale was his concern in the fractured times when the modernist visual artists, like their literary counterparts, were struggling to find individual voices and styles to respond to specific historical moments.

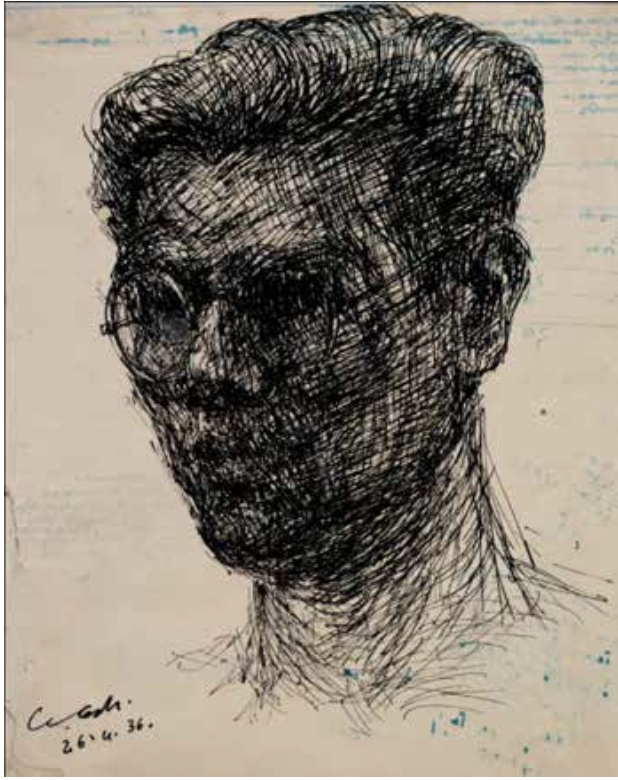

Ash mastered many mediums and innovated many forms as we see his sketches in pencil, pen and ink, paintings of landscapes and human figures in water colour, gouache and oil paint using paper, board and wood as his surfaces. From the young age of 27 to the ripe old age of 89, he continued to produce self- portraits. The viewer is encountered with an array of Ash’s faces as they start traversing the display space at the KCC, as an intimate chronicle of Ash’s exploration of himself as a person, a visual artist, and a mortal being who adds the years of his lived experiences to his physical self. The medium of pen and ink enlivens a threatening tactility between the subject and the self, connected through keen observations that don’t miss a hint of brutality. Darkness thickens below the eyebrows with the masterly laying of the crosshatched line. Darkness disperses as the lines disappear from the forehead or nose or cheeks, as if with the glow of light emanating from within. As Ash ages, the artistic styles change with his facial muscles sagging, his hair receding, his lips and eyes wearing the heaviness of experience. His lines started varying on the paper. From being intensely dense, they start flowing more freely to finally take on the form of a caricature, teetering on the verge of self-mockery.

As part of the Art Rebel Centre collective, together with Abani Sen, Annada Dey and Bhola Chatterjee as his compatriots, Ash was instrumental in organizing an iconic exhibition of 150 submissions along with 50 paintings of the four members of the ARC in 1933.

This exhibition and the others following this, mark the contours of modernism in the Kolkata chapter of visual arts. From this time, Ash started exploring the rural landscape as an itinerant painter and continued to sketch extensively across the districts, which included his trips to Ranchi, Hazaribagh, Mayurbhanj, Murshidabad and a sojourn on a boat along Padma River en route to Dhaka. What he observed and absorbed in thesejourneys, the vast fields mellowed with the glow of the afternoon sun, the shimmering expanse of the rivers, the dense jungles, the rain-soaked barks of the trees, the shadows that gathered and deepened around the villages as dusk fell, all entered his landscapes. But his landscapes, in gouache, water colour or oil paint, never appeared without its poverty-stricken labouring protagonists like Tillers of the Land. He became a flaneur during his stay in Kolkata from 1926 to 1947, like another contemporary of his, the poet Jibanananda Das (1899-1954), and continued to walk along the streets to sketch streets, market places, cowsheds and the Howrah and the Sealdah stations. An instance of this can be found in Fakir, a portrait made of a Muslim mendicant in Park Circus, which was published in Bangasree in 1939.

On sketching, Ash said:

“Sketching is like a world tour. I wander the world through sketches. Travelling on a lifelong pleasant journey in artistic life, the sketch is my best friend and companion. A heartfelt approach, formless, boundless, freely, frankly, and boldly to speak with aesthetic research in an artist’s career for all ages.”

In 1948, he started his avant garde Avatar series where the figures he came across in real life attained semi- abstract semi-mythological forms with impressionistic pointillism (tinges of Prussian blue, yellow ochre, grey, white, green) or solid thick layers of colour (sometimes four layers around a figure). In their primordial formations of facial features and countenance, these figures in Tribhanga, Village Woman, Mother and Son, Moshgul,Hypocrite, Childish, Two Sisters and others in the series show Ash’s individualistic stylization throughout the 1950s. In its organic primitivism, the Avatar series brings back the memory of the pattachitras (scroll painting), but at the same time, signals the multiple capacities of form and the possible meanings beyond the traditional limit by offering scientific arrangement of colour (dots and layers) to depict the characters with individual personality traits. The Avatar series reminds us of what Ash said:

“If we look at nature in the open, we do not see individual objects each with its own colours but rather a bright medley of tints which blend in our eyes, in our minds.”

Gobardhan Ash’s Famine Series visualised the man-made great Bengal Famine (1943) by using a wash of earthly brown tones, blurring the lines and dissolving the famine-stricken figures with the undifferentiated background where nothing exists. His medium of showing the stark misery in rural Bengal paradigmatically differed from the preference for black and white of other artists of famine, namely Zainul Abedin and Chittaprosad.

In 1950, Ash joined the Calcutta Group and later on became a part of the Progressive Artists’ Group and continued to experiment with forms, mediums and subjects (marine creatures, exhibited in 1955, a set of animals — buffalo, horse, lion, street dogs — and a series of human portraits). His portraits included nameless male and female figures (Portrait of a Housewife, exhibited in 1954, New Delhi) and iconic personalities like Ramakrishna and Sarada (1960). Portraiture enabled Ash to cover his basic expenses for living and art material costs. The Calcutta Group, of which he was a part, disbanded in 1953. In 1955, Ash left his position as the Head of the Painting Department that he had taken up at Atul Bose’s request in the Indian Art College, and went back to his solitude to cultivate his art further. He chose his native village, his birthplace Begampur in Hooghly district, as his home and workplace for the rest of his creative life. There, he opened the Fine Art Mission Free Arts School in 1956.

Between 1957 and 1967, Ash crafted the Children Series, a collection featuring sketches and oil paintings of children. These portraits, almost resembling each other, depict infantile innocence. But the viewer also perceives some inexplicable symbolism when they stand in front of a wall featuring multiple faces with plump cheeksandun defined features.This uneasy effect gets heightened with the main image, Commander-in- Chief, where three children appear resembling each other’s innocence. The child in the middle stands with a whip in his hand while the other two look on. Theincongruity of soft flesh and softer expressions and the uninhibited power that they unknowingly handle and inhabit, provides no easy unilinear meaning, and rather exposes the illogic of power itself.

This retrospective that came 94 years after Ash’s first solo exhibition in 1930 (at the Calcutta University Institute) is an important endeavour for archiving and curating Ash’s lifelong work. It is not only a display of Ash’s canvases or panels, but also an interpretive effort to place the growth of an individual artist’s various styles in response to his contemporaries and political- social nuances of the times that he lived through. This retrospective also gives the audience a historicised understanding of Ash’s constant attempt at self- introspection and translation of his inner turmoil in radical forms of art as he engages with the vulnerabilities and deliberations of post-independent India.

Gobardhan Ash Retrospective, Curated by Brijeswari Kumari Gohil and Harsharan Baksh, Kolkata Centre for Creativity Presented by Princeps, Kolkata, March 29 – April 21, 2024.