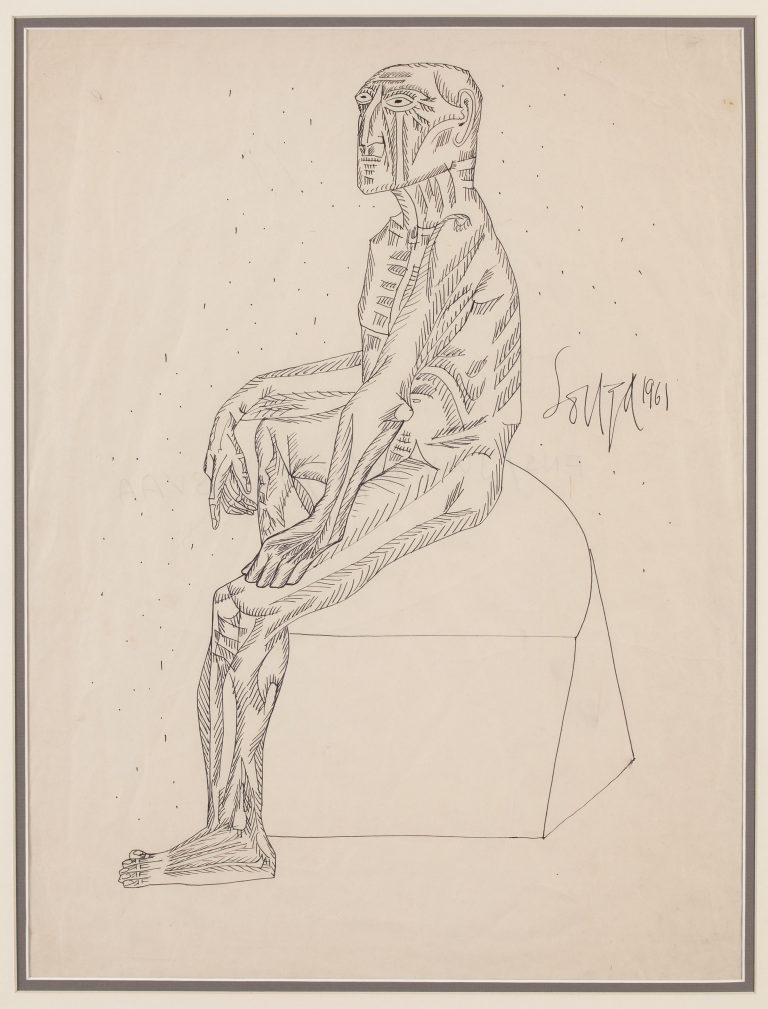

Vivan Sundaram’s retrospective at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art was a testament to the unique variety of his oeuvre. Curated by Roobina Karode, the exhibition titled ‘Step Inside and You are No Longer a Stranger’ contained a dozen stylistic departures and arrivals. Each room in the museum’s maze of galleries, offered a new formal encounter: amusing pop juvenilia; vivid, semi-abstract canvases; brooding charcoal landscapes; gorgeous, large-scale oils dominated by strong figures; a sombre room of beds created with shoe soles and rusty metal frames; a riverscape made of thick, handmade paper stained with engine oil; an immersive light-and-sound piece inside a giant boat-shaped container; an ominous video tracking across studio sculptures and detritus; and many more.

Mastery of one medium being an extraordinary challenge, proficiency in so many feels almost unfair. There ought to have been hints of awkwardness somewhere, but the display contained no signs of hesitation and uncertainty. Even the self-deprecatingly titled Bad Drawings For Dost, composed as a homage to Bhupen Khakhar, were startlingly delicate replicas of Khakhar’s drawings remade through cutting, folding and stitching translucent tracing paper. Having followed Sundaram’s output since the mid-1980s, these drawings, like most of the other pieces in the show, were second encounters for me. To view artworks after a gap of 10, 20 or 30 years, sets up a dialogue between new and remembered responses. I was apprehensive that paintings like Ten Foot Beam and Big Shanti, which had been my introduction to contemporary Indian art in junior college, and have remained as precious memories, would appear feeble in relation to all I’d viewed in the intervening years. Happily, they retained all their beauty and power, and the nostalgia I felt in their presence was unmixed with the sense of loss that is nostalgia’s frequent companion.

If those large canvases have aged well, so has Sundaram’s body of work as a whole three-fourth of the paintings made in London in the late 1960s, recently rediscovered and restored, contain so much movement and energy that they almost leapt out from the museum walls. However, with each room employing different materials and creating a different mood, I was left questioning what, if anything connected one phase in the artist’s journey with the next, apart from his name. To pose this question is not to ignore underlying themes that persist from his early maturity to his latest creations, such as his concern of memory and history. The Auschwitz death camp, the killing of Safdar Hashmi, the Gulf War of 1991, and the 1946 Bombay sailors’ mutiny are among the historical events that have found echoes and reflections in his work, alongside the depictions of his grandfather Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, his maternal aunt Amrita Sher-Gil, and close friends and associates. Nevertheless, each new stage in Sundaram’s journey rarely seems predictable, even in retrospect; it does not convey the impression of necessity perceived in the development of most major artists. Nothing I knew about the artist’s previous endeavours would have helped identify him as the co-conceiver, along with Ashish Rajadhyaksha, of Meanings of Failed Action: Insurrection 1946, a sound installation paired with an archive of documents about the Royal Indian Naval Mutiny and its fallout. Unlike the peers with whom he exhibited in the seminal show Place For People – Jogen Chowdhury, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Bhupen Khakhar, Nalini Malani, and Sudhir Patwardhan – and indeed unlike any renowned artist I can think of, Sundaram has never developed what can crudely be termed a signature style.

The most interesting comparison in this respect is with Malani who, along with Sundaram, pioneered Indian art’s shift away from traditional painting and sculpture into installation and media art in the early 1990s. Having established a characteristic style of painting over the course of three decades, she retained a sense of continuity while exploring new terrain by incorporating her signature figuration into the spectacular shadow plays that became her best-received artworks in the current century. Although Sundaram has received several accolades in India and abroad, it would be fair to say that he has yet to achieve the same degree of acclaim as Khakhar and Malani. Given how prolific, ambitious and influential he has been, I can’t help wondering if some of the gaps between him and those peers can be explained by the absence of immediately identifiable attributes across a significant range of his creations.

Taking the issue further, it is possible that long periods of delving into the same compositional patterns, while carrying the risk of formulaic repetitiousness, also open up accretive, cumulative effects in which new iterations build upon previous ones in a manner not available to an artist like Sundaram, whose style is distinguished by ruptures and jumps. If this is true, signature style might involve something deeper than accessibility or market friendliness.

To return to the artist’s retrospective from broad speculation about his significance and potential legacy, the display constantly switched between figure and implied figure. We could use, as examples, a portrait of Karl Marx created in the early 1970s, and a large canvas of a broken window painted a few years after, the title of which was borrowed for the exhibition as a whole. The smashed glass revealed the remnants of human action, and implied human presence of a specific kind. Where figures were present in the works on view, they were friends, family members, heroes, martyrs, and labourers, viewed with sympathy. Implied figures, known through their effects on their surroundings, were usually associated with violence and rapacity. Taken together, these depictions of individuals and implied individuals, examined the most urgent concerns of our era, like nuclear war, environmental degradation, displacement, migration, and the surveillance state, while also speaking with eloquence of camaraderie, solidarity, loneliness, intimacy, and compassion.

‘Vivan Sundaram A Retrospective: Fifty Years Step Inside And You Are No longer A Stranger’, curated by Roobina Karode, 9 February – 20 July 2018, Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi.

All images courtesy: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art.