Moving away from a conventional formalistic or stylistic review of artworks featuring in the exhibition I resort to a careful study of the ideological, conceptual and aesthetic dimensions presented in the solo exhibition of Waswo X. Waswo and R. Vijay titled ‘Like a Leaf in Autumn’. Such careful readings based on individual works from this solo exhibition are available in the public domain. I depart from this method to open up the possibilities that are presented in this exhibition but not limit myself to that event. I feel that a detailed analysis of Waswo and Vijay’s exhibition would be incomplete without considering the figures of the curator, connoisseur, critic, collaborator, and most importantly the ‘Evil O.’—the passionate antagonist of post-colonial theory—coalescing in Waswo X. Waswo. Through this figure, Waswo has presented an overarching critique of postcolonialism and specifically its theoretical foundations rooted in Edward Said’s iconic Orientalism that continues in this exhibition. I sincerely understand that, at the core of Waswo’s artworks, ideology, politics, and concerns there is an attempt to dislodge the operative binaries that govern the theoretical premises set by postcolonialism and Marxism. Nevertheless, instead of moving beyond these binaries to overcome the political legacy of colonialism Waswo also resort to these binaries and homogenisation. This aspiration to move beyond the fraught binaries is laid out in the writings of Mahmood Mamdani and I sincerely feel that Waswo could hugely benefit from a critical engagement with postcolonialism. Mamdani argues that both Marxism and nationalism have failed to maintain an analytical distance from colonialism and could not historicize race and ethnicity as political identities reproduced by colonial institutions. I would add the category of political conservative thinkers to this list who also failed to detach fascism from liberalism and failed to see how liberal ideas were instrumental in the propagation of colonialism and imperialism. To analyse the rise of aggressive nationalism and fascism in the contemporary context is not a task one should separate from the intersected legacies of fascism and colonialism, that appear across the media, ‘within the historical inclusions and exclusions of art and culture, and in a nation state’s so-called traditions as well as its denial of basic human rights.’

This is where I also feel that these intense interventions from Waswo’s side could be instrumental in exploring the unresolved politics of colonialism, affecting a range of subjectivities involving both postcolonialism and the politics of asylum. Waswo’s works cover themes such as intimacy, affect, and embodiment and interrogate the paradoxes of both colonialism and postcolonialism. I have divided this review into different sections to accommodate these concerns in their work to address the complexities which are presented.

Race, Racism, and Whiteness

Waswo does not pretend to be ‘colour blind,’ a coinage used by Gloria Wekker to criticise the indifference to racism in the white world. Citing an example of this posture, white innocence, she notices how the structurally and personally privileged would say, ‘We do not do race, we do not see colour. Woah! I didn’t even see that you are black’ as a compliment but would not accept the inherent racism in European societies. Unlike this, Waswo acknowledges the toxic fiction of race and examines the whiteness in his work and life. His works especially the photographs and miniature paintings present the possibility to analyse the historical and political relationship between colonialism and nationalism. By undertaking this task, one will understand that this relationship is a fraught double bind as argued by Albert Memmi in The Colonizer and the Colonized:

In the face of Nationalism an undeniable uneasiness exists in the European left. … Being on the left means not only accepting and assisting the national liberation of the peoples but also includes political democracy and freedom, economic democracy and justice, rejection of racist xenophobia and universality, material and spiritual progress. Because such aspirations mean all those things, every true leftist must support the national aspirations of people.

Recent scholarship has made significant interventions to critically interrogate the binaries and argues that they exist in contradictory relations to each other. They move to expand the notion of the political arc (colonialism-nationalism-fascism) by arguing that political history now appears more like a fold and ‘recognises no binaries or absolutes, and even though ideas are distinct, these distinctions are continuous and without discrete ruptures’ (Nick Aikens, Jyoti Mistry, Corina Oprea, 2019). For them, the metaphor of fold presents flexibility that does not recognise any binaries and absolutes. They show how nationalism is a term that is appropriated by both the left and the right. The fact remains that European colonialism has established itself through the oppression of others and it continues its refusal to be recognised as such. It is a problematic situation and only through these continuous critical interrogations one could unravel the contours of this reality especially when economic expansion and exploitation is a continuing one. This exploitation is also carried out by the erstwhile victims and now by the neo-colonisers from Asia. For that, they resort to the various modalities, racial brackets/categories and technologies, which were invented as part of the colonial expansion. This is where I feel the necessity of art practices, institutions and expressions articulating these connections from their respective geopolitical positions.

While observing works such as A Day on the Farm, In Search of Mystic Mandir, Observationist in a Stolen Garden, The Reader, and The Scholar, I could only think of James Baldwin’s experiences as a black man in an all-white village shared in the essay called Stranger in the Village. It presented an opportunity for me to contrast both experiences of Baldwin in a Swiss village and Waswo’s long stay in the rural hamlet of Udaipur. Being there in the village of Leukerbad as a black man at the heights of racism was not only a dangerous task but a depressing one too. Baldwin remarks, ‘The children shout Neger! Neger! as I walk along the streets.’ He compares his experience with that of an earlier white man who would have landed in an African village to state the difference between his visit and the white man’s visit. Baldwin says,

But there is a great difference between being the first white man to be seen by Africans and being the first black man to be seen by Whites. The white man takes the astonishment as a tribute, for he arrives to conquer and to convert the natives, whose inferiority in relation to himself is not even to be questioned; whereas I, without a thought of conquest, find myself among a people whose culture controls me, has even, in a sense created me, people who have cost me more in anguish and rage than they will ever know.

Unlike Baldwin’s white man Waswo’s protagonist is not a conqueror. He is a refugee. Modelled on Waswo, he realises his privileges and differences, also cherishes the hospitality he enjoys and laments the difficulties he had faced to establish a career, political expression and free expression of desires. Moreover, he is a sensitive partaker and a critical observer of the history, culture and politics of his host nation. Waswo’s works, writings, collaboration with R. Vijay, engagement with young curators/writers/artists, and curatorial interventions in the South Asian miniature tradition opens up the possibilities to move beyond the binaries such as coloniser and colonised, oriental and occidental. Rather his practice offers a direction to engage beyond these binaries and explore the diversity of relations, some more clearly antagonistic than others. These binaries do not consider the development of different layering as Linda Tuhiwai Smith writes, ‘Unlocking one set of relations most often requires unlocking and unsettling the different constituent parts of other relations.’ Such a radical demand already exists within the decolonising strand, it does so by carefully analysing how people in both European and non-European countries were brought and governed under imperial system, patterns of migration and displacement, and most importantly how imperialism dehumanised not only the non-Europeans but also the white subjects. Toni Morrison in an interview with Paul Gilroy talks about what slavery in the US did to the white psyche:

Slavery broke the world in half, it broke it in every way. It broke Europe. It made them into something else, it made them slave masters, it made them crazy. You can’t do that for hundreds of years and it not take a toll. They had to dehumanize, not just the slaves but themselves. They had to reconstruct everything in order to make the system appear true.

Therefore, while foregrounding the anxieties of oscillating between the refugee and yet to arrive coloniser, Waswo can extend this discussion to show how race and whiteness are implanted so deeply in our cultural archives. Like Gloria Wekker proposes, ‘We need to become aware of and then dismantle our cultural archives, especially the benevolent, superior images of white people and the toxic, inferior, images of people of colour which are cemented there.’ Waswo and Vijay’s project has the potential to reclaim the miniature tradition, especially to liberate it from the confines of South Asian cultural history and infuse it with a renewed cosmopolitanism. Contemporary South Asian miniatures redeemed itself from the nationalist trappings and the artists have used it effectively to create political allegories, recast political representations, and explore questions of identity, gender, domesticity, political violence, and interiority. The ironic and playful potential of these miniatures could be further enhanced through Waswo’s sharp witticism and conceptual rigour.

Politics of Landscape

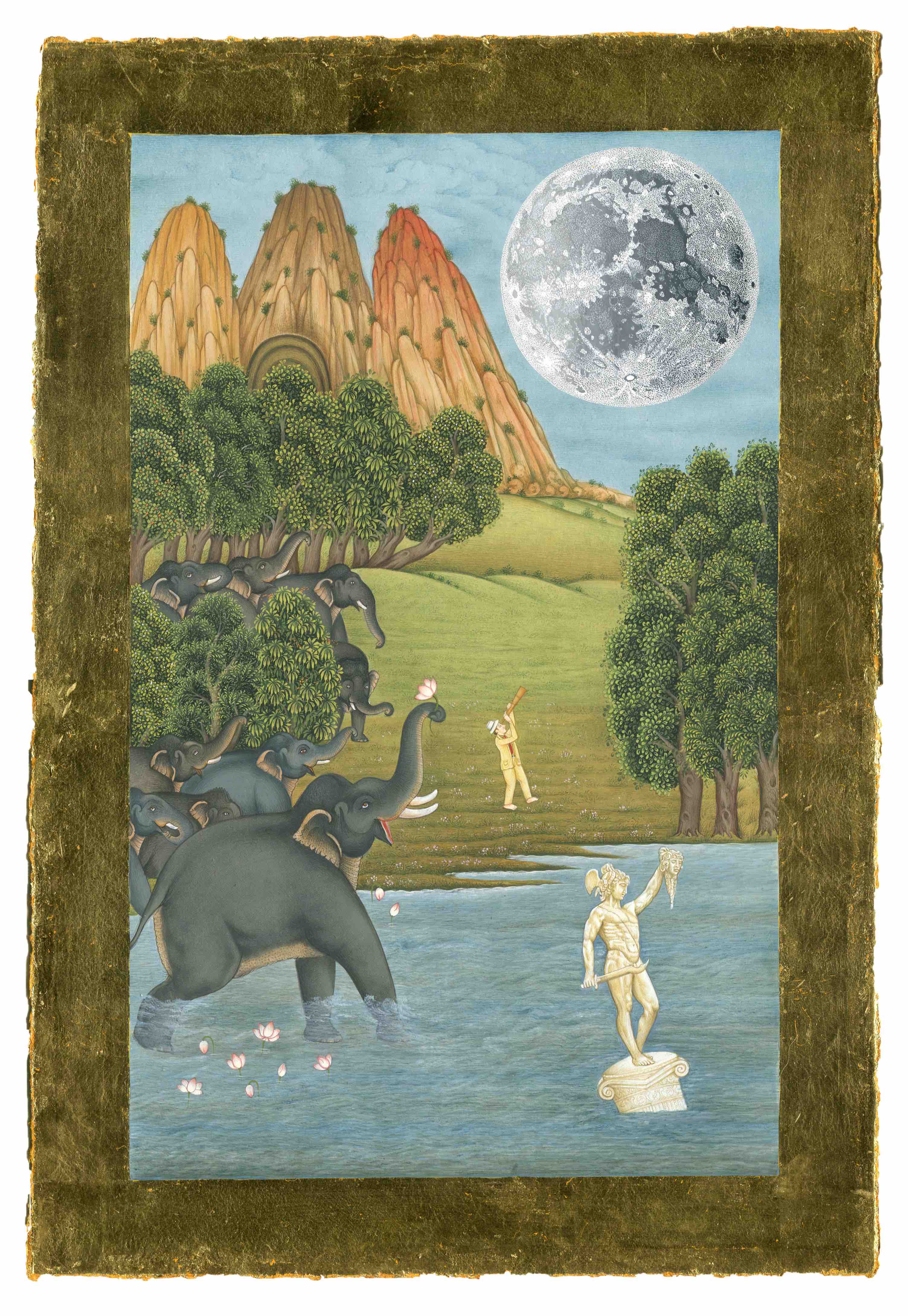

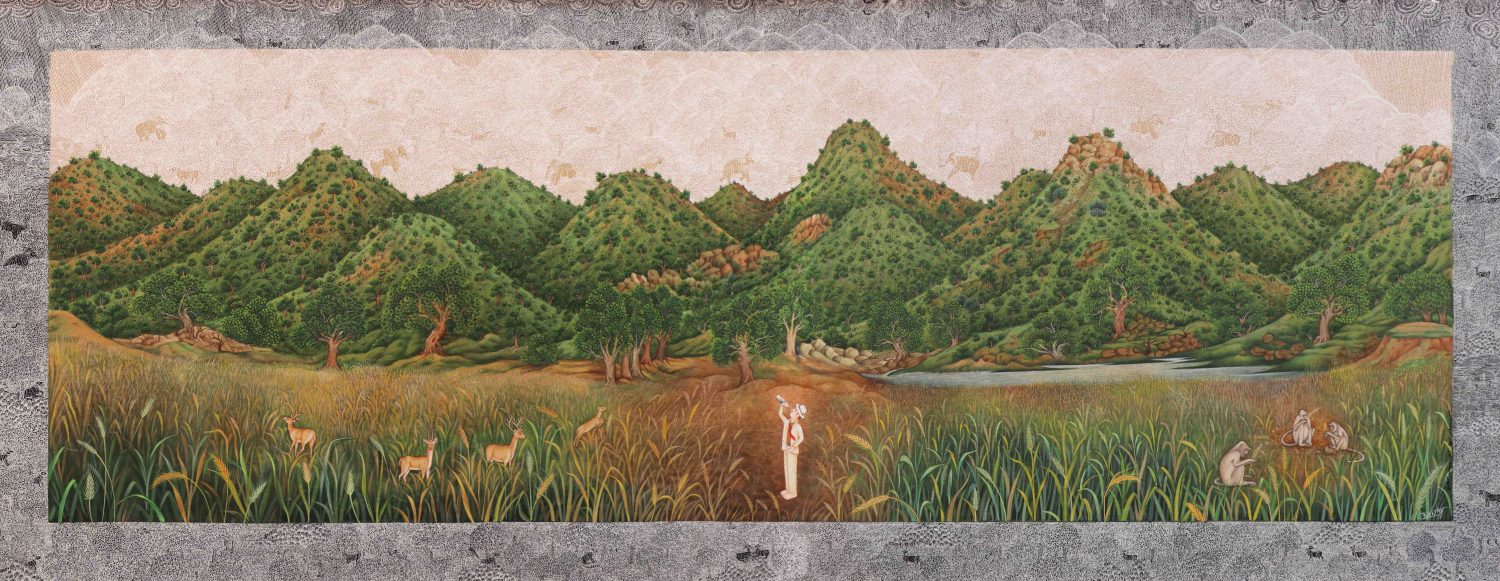

Majority of the paintings in the exhibition feature idyllic landscapes characteristic of miniature painting. A wide range of backgrounds from the South Asian miniature tradition is mobilised as a backdrop for the individual actions to unfold. Despite Waswo and Vijay’s extensive experience and knowledge of the miniature visual motifs, the proliferation of these diverse visual motifs does not extend itself to a conceptual discussion on landscapes, the politics of land, appropriation. The clarity and sharpness with which Waswo used to engage earlier with miniature tradition, and his comic self-referential white presence and the courageous wit to provoke the postcolonial lobby have been diluted in the present series of works. They are beautiful renderings but the landscape is reduced as fragments of citations instead of launching ferocious attacks and passionate reclaiming. The tone of resignation in the exhibition title is especially bothersome for me because of these reasons, especially considering his recent involvement to assemble the range of miniature practices in a recurring exhibition format along with well-researched publications and seminars. The present moment requires Waswo’s passionate and insightful engagement with the practice of miniature more than ever.

As mentioned previously, the various modalities deployed by the colonial system had surveyed, ordered, renamed, and categorised the land. The attempts to survey and control the land physically was coeval with ordering and visualising it as idyllic landscapes. The picturesque prints and watercolours of Hodges and Daniell claimed to represent an objective view of India contra to the existing native visual repertoire. The land was renamed and landscapes were reconfigured. Colonial expeditions, surveys, and visual representations were replete with references of the ‘virginal’ land (terra nullius) waiting to be discovered, appropriated and controlled. Gurminder K. Bhabmbhra observes that ‘the European nation-state was central to the development of the colonial settlement project (most notably Spain and Portugal, followed by Britain and France), as were the movements of European populations, including people from Scandinavia and Eastern Europe.’ He points towards the long-standing association between the idea of the citizen/subject and their entitlement to land, even if occupied by others, brings twentieth-century fascism and current anti-migrant sentiment into the nexus of activities that must still be understood as colonial—this is particularly so as Europe today claims that it is unable to sustain the presence of others. Colonial settlers were never considered as migrants, rather they normalised and legitimised their migration.

In this context, the mere placement of a self-referential figure engaging in adventures, ruminating, and titillating appear as a passive gesture. The imagery of refugee and colonialist merging together in Waswo’s works can identify, interrogate, deconstruct, and replace hierarchies and operative binaries governing art history, theory, and political representation. In his paintings past and present historical moments interweave unravelling themes of displacement, cultural syncretism, and the search for identity. What stands out and could be further elaborated is the politics of place in the contemporary context where exile, displacement, and borders intersect with each other. The various landscapes mobilised in these paintings present opportunities to dispel the fear of the other and rethink and reformulate an inclusive space of asylum.

The Empire Writes Back: Vijay’s Evil O.

Finally, before concluding this review I would also like to expand my thoughts on the nature of collaboration between Waswo and Vijay. The nature of this collaboration is pragmatic as stated by Waswo and Vijay on various occasions. Waswo conceptualises the overall theme and visualisation of each work, whereas Vijay executes them. The important question for us to ask is how is this collaboration internalised? Is it accepted beyond question both in the art world and also among its agents? Both Waswo and Vijay had shared a great deal about the struggles and oppositions they have faced about the authorial identity of these works. Waswo has also shared how many buyers preferred only his name to be added to the work and wanted to erase the contributions of Vijay. We all know that the internal mechanisms of a commodified art world will always like to harp on the star value of the established artist. Waswo and Vijay have subverted this very idea of stardom and struggled to make the collaboration apparent. Nevertheless, I am more fascinated by the tensions between these two agents as part of the collaborative process. I would like to trace the evidence of this confrontation in the protagonist who appears in the paintings. I believe that any sort of collaboration ideally should not be peaceful and passive rather it should be filled with antagonisms. Therefore, it is also important to move beyond the visible struggles of these two figures and excavate the psychological foundations of this collaboration. What is the nature of ‘identification’ between Waswo and Vijay, i.e., the psychological relationship between two individuals? Imaginations enable a subject to perceive them to another and extend the possibility to position them in other’s place. Why have we not shifted the frame from Vijay’s perspective and examined how is he connected with the protagonist? After all these years of close engagement with Waswo and the character Evil O. has he ever felt like appropriating it? I would like to imagine that it is not Waswo or the self-referential Evil O., who appears in these paintings, rather it is the affirmative presence of Vijay that emerges in front of me. Would it be also possible to conjure that Vijay dismantles the orientalist and writes back to the Empire by recovering or developing an effective identification with the self and place? To conclude, the protagonist Evil O. is more than an image or representation, it is more than a memory or a subject. The protagonist is the unconscious of this collaboration. The body, desire, and pleasure merge with this unconscious. It does not wither away like a leaf in autumn.

Waswo X. Waswo and R.Vijay, ‘Like A Leaf in Autumn’, 11 October–11 November 2019, Gallery Espace, New Delhi.

References

Gurminder K. Bhambra, On European ‘Civilization’: Colonialism, Land, Lebensraum, 2019.

Gloria Wekker,On White Innocence, 2019.

Rex Edmunds and Elizabeth A. Povinelli, A Conversation at Bamayak and Mabaluk, part of the coastal lands of the Emmiyengal people, 2019.

Nick Aikens, Jyoti Mistry, Corina Oprea, Living With Ghosts: Legacies Of Colonialism And Fascism, 2019.

James Baldwin, Stranger in the Village, 1953.