“We can interpret the economic process as alchemy if it is possible to arrive at money without having earned it through corresponding effort: if the economy is a top hat, so to speak, which yields a previously nonexistent rabbit: in other words, if a genuine value creation is possible which is not bound by any limits and is, therefore, in this sense, sorcery or magic.”

—Hans Christoph Binswanger, Money and Magic: A Critique of the Modern Economy in the Light of Goethe’s Faust

The speculative science fiction Money and Magic: A Critique of the Modern Economy in the Light of Goethe’s Faust, written by German Hans Christoph Binswanger, traces the unspoken significance of monetary value in Goethe’s Enlightenment-era literary work Faust. The tangible circulation of the paper money that cajoles Faust to sign a doomed deal with the devil determines the survival of the modern economy. The power intrinsically tied to money follows the pattern of ebb and flow, only to make Faust realise the enticing magnetism of money. Drawing from literature, Binswanger knits the web of the hegemony of ownership, economic exploitation, and ecological crisis. The concerns to which Binswanger pulls our attention find familiar ground in the field of art and aesthetics—trod by art makers, curators, collectors and enterprisers. Economic gains as and when control the event of art making, the promise of magic finds itself irresistible to the number game. When such debates meet discomforting silence they advertently indicate the matter of importance. To override this, the fifth edition of Delhi Contemporary Art Week (DCAW) 2022—held at the sprawling Bikaner House, New Delhi—pushes the discussions around art and economy with a spectrum of young contemporary artists.

The exhibitions by the seven participating galleries—Blueprint 12, Exhibit 320, Gallery Espace, Latitude 28, Nature Morte, Shrine Empire and Vadehra Art Gallery—harnessed the exponential rise of interest in the art market when the shadow of the global pandemic began to recede. The bouts of isolation and abandonment, the corollary of COVID-19, bestowed a sense of self-introspection. The turn to art as a way of reflection also raised curiosity about art investment, even when there was a critical break in the tactical experience of the art. While the production of art, to an extent, survived the overpowering constraints exercised in the last two years, the need to make it accessible far and wide gained momentum with gallerists and collectors alike.

DCAW 2022 also has a special exhibition ‘Legal Alien’ curated by Meera Menezes. It is a walkthrough of legal networks instrumental in creating a sense of alienation. The web in which human life is caught largely weaves threads around self-realisation (the subject of classic philosophy discussion) and alienation (the topic of interest to Marxist intellectuals). If the former indicates the best of human potential to meet the purpose of human life, then the latter hints at social and psychological misfits. Alienation as a phenomenon of modern liberal society has cemented itself into human life with little scope for debilitation in the post-truth era. Perceptibly, the dawn of the pandemic removed the lid from the many layers of estrangement that were known yet rendered invisible in the life of a hustler. The piercing effect of alienation put into force with the tools of political bureaucracy is borne by the people navigating the routes of migration anchored and the landscape of exploitation. Legal supremacy, political unrest, climate change and urban development find visual articulation in ‘Legal Alien’.

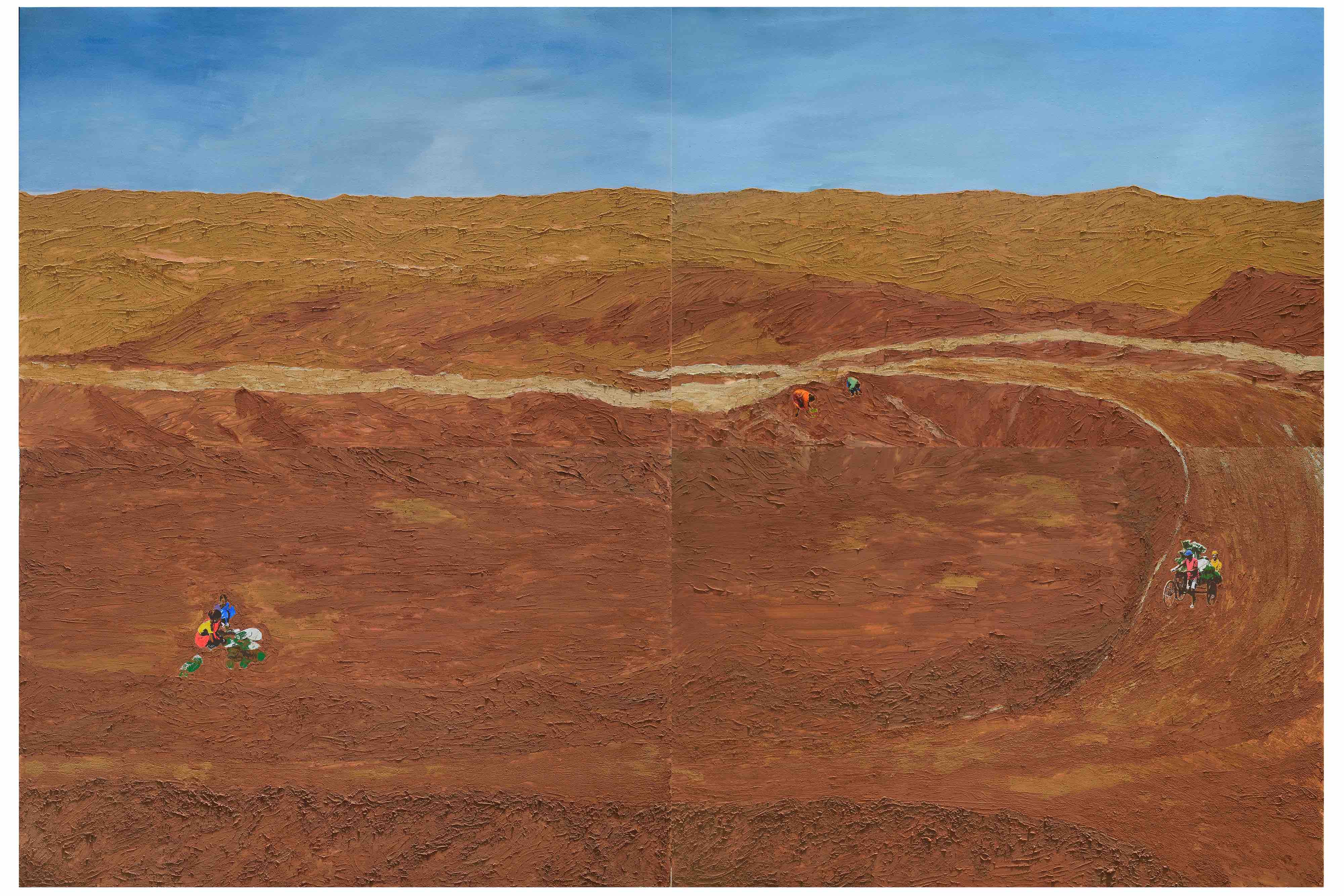

The solitude figure standing in the middle of a lush green backdrop in the photo series Where the Flowers Still Grow by Bharat Sikka (represented by Nature Morte) opens the spiralled turmoil of alienation experienced by the people of Kashmir—one of the highly militarised zones on the global map. The perpetual sense of alienation, being homeless in a home, dominates these photographs. The use of soil by Sangita Maity (represented by Shrine Empire), to prepare serigraphy on the surface of Industrial Acquisition IV, sourced from the region rich in minerals, Chota Nagpur (sharing state borders with Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal), leaves a textured look and feel. The grainy surface transmutes into a metaphor for the uneven journey undertaken by the people who experience dispossession and dislocation—a corollary of urban development. The extraction of minerals from the land to meet the needs of economic profits has disproportionately anchored uprooting from the home and led to a sharp dive into the abyss of alienation.

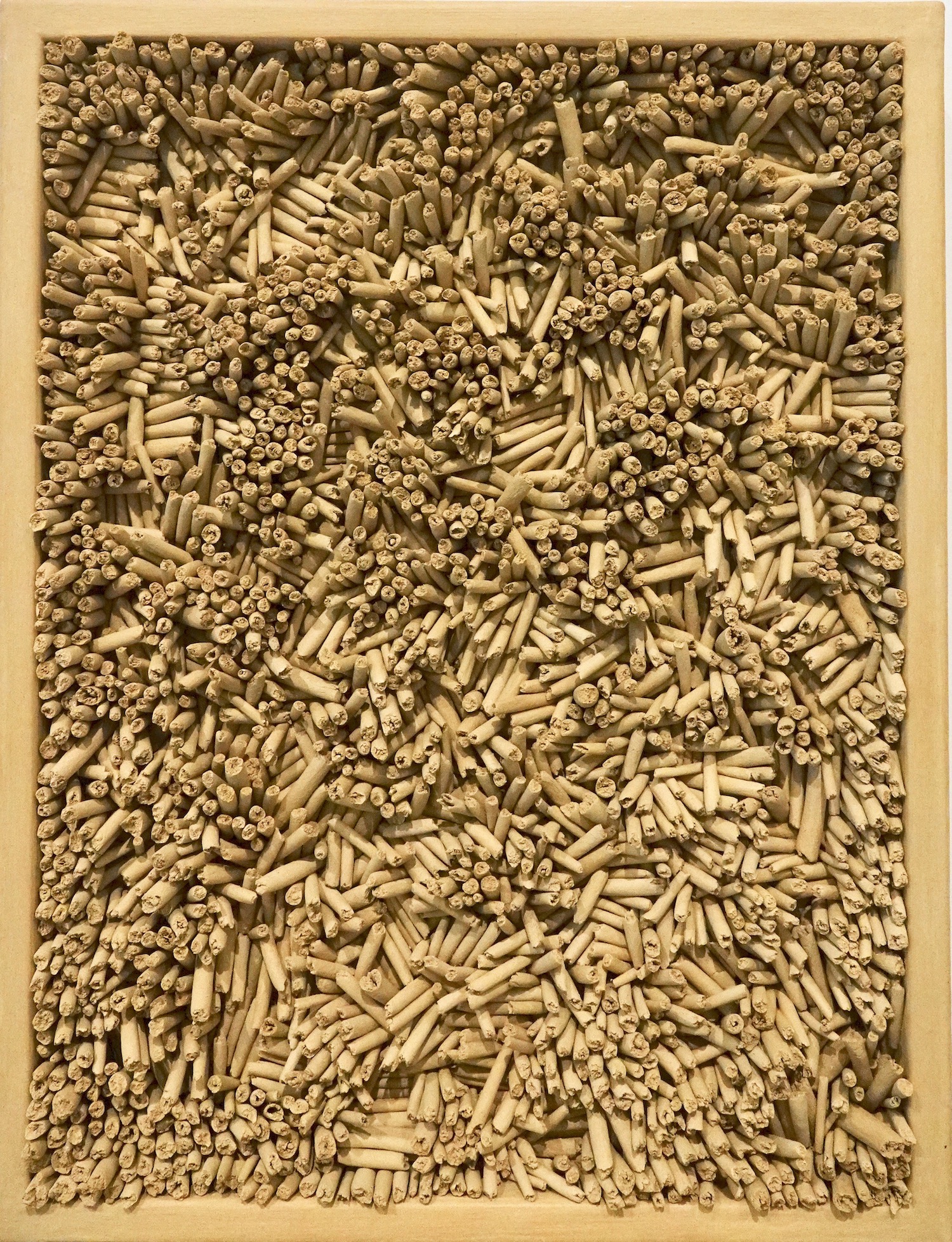

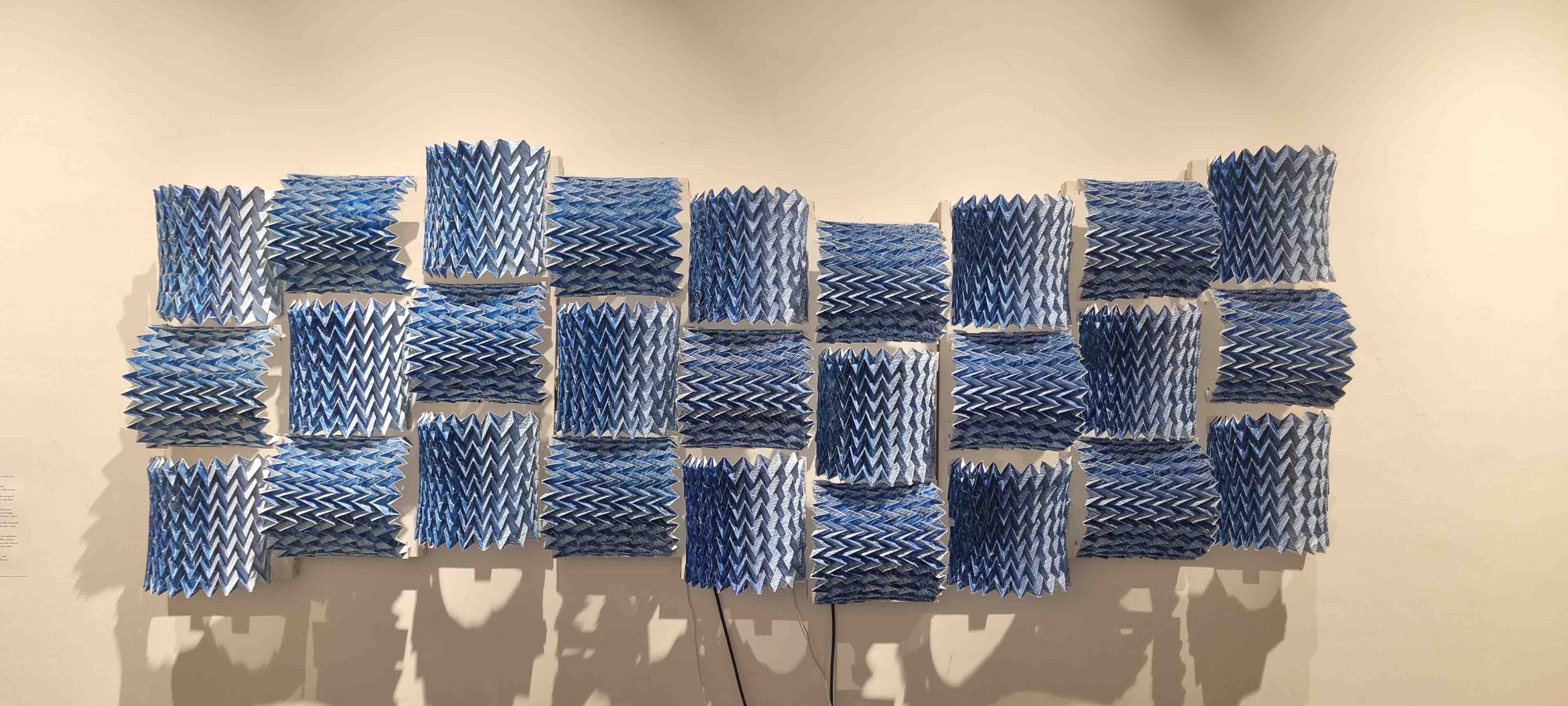

The Centre for Contemporary Art Building, Bikaner House, is a minute’s walk from the Old Building and offers a visual feast. The galleries ensure there is an art to admire and learn from for every person who steps into the double-storey heritage building. Exhibit 320’s artist Gunjan Kumar with her series of sculptural installations The Weight of Time encapsulates the passage of time. The cluster of miniature-sized shreds carved out of bentonite clay or multani mitti prompts a journey down the memory lane. The historicity of the multani mitti, found in abundance in the Indian subcontinent, rightly meets the importance of material and process that Kumar holds in her art practice. For the viewers, the kinetic sculpture An Ocean in a Drop by Aditi Anuj (represented by Blueprint 12) is a breath of fresh air to the series of artworks. When kinetic art is still at a nascent stage in the Indian art scene, it is largely practised by trained artists within the parameters of the infrastructural support and facilities available at the disposal of the institutions. Against such a backdrop, An Ocean in a Drop serves as a window to the many possibilities open to contemporary artists.

Sachin George Sebastian with a sculptural installation Untitled from the Duality Series, as a part of Vadehra Art Gallery’s curation Remember The Skin Whose Earth You Are, encircles the complicated coexistence of urban life and ecology. The materiality of the paper stands as the point of analogy for the fragility of life when overpowered by the order of cityscapes. Gallery Espace dedicates space to ecological concerns with the botanical installations on the lower floor of the buildings. The human-size sculptural installation Cymbidium Tigrinum by Valay Gada opens the inner and outer sections of the flower to acquaint the viewers with the beauty bequeathed to nature, but withered under the spell of human excess. The layers of the acrylic paint lend a texture to the traditional paintings that are now swapped out for the play of computer-generated images in the work Let’s Go West by Aditya Pande, represented by Nature Morte. In the age of post-internet art, digital painting showcased the delicacy of the environment with the aid of digital photographs to talk about the shift in sense perception from the viscosity of paint to the resolution of pixels.

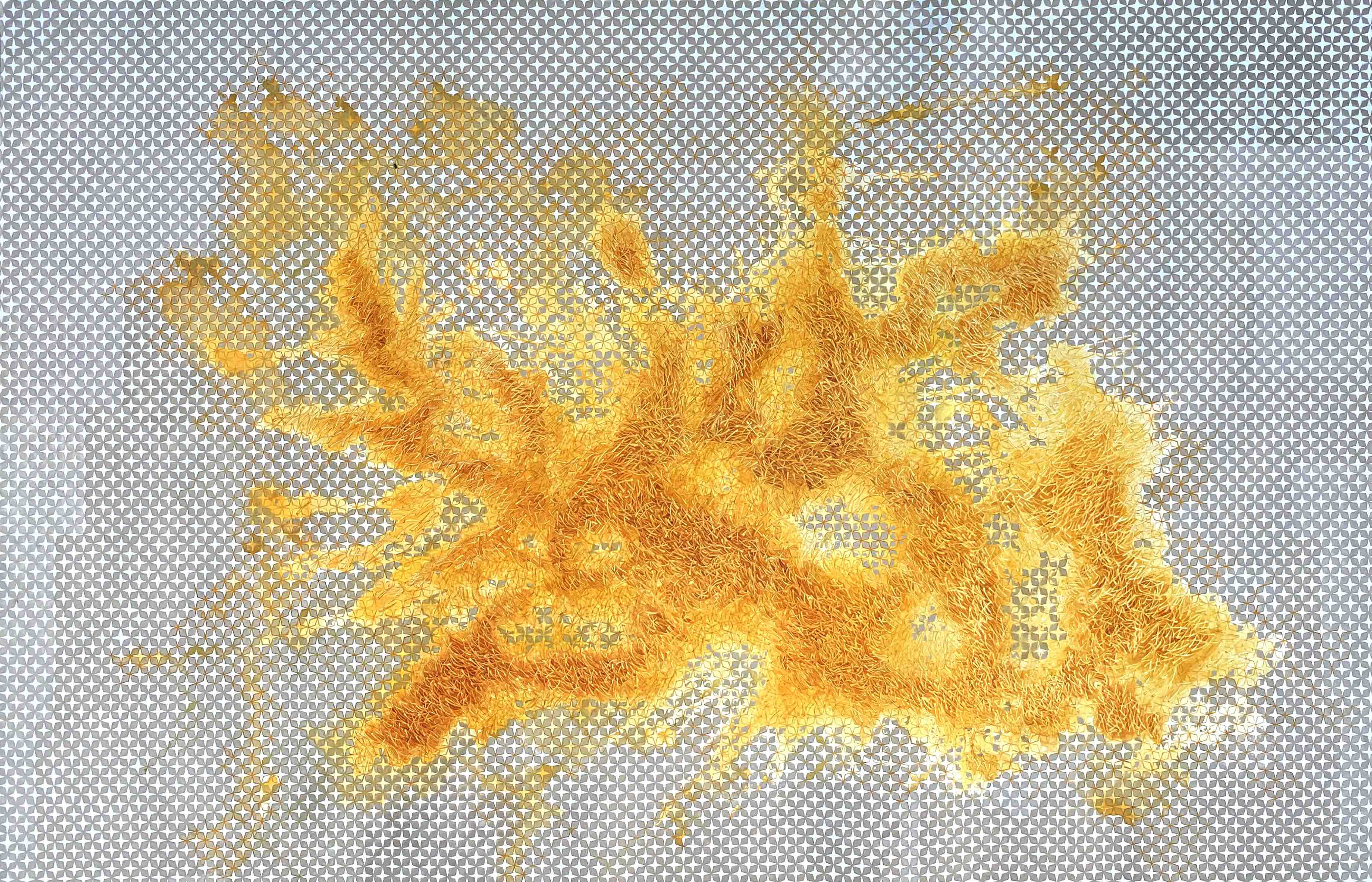

Contemporary art in India at large is an uncontested site which immortalises the lineage between traditional and modern art. The artists Gopa Trivedi and Waswo X Waswo, both represented by the Latitude 28 at DCAW, revisit miniature paintings and studio photography respectively to develop their distinctive visual language. Under the lens of contemporary social tensions, the Indian miniature techniques and ‘jali’ motif are not transplanted as an extension of beauty in the painting Bleeding Saffron by Trivedi but regain political valency as soon as the deep yellow and orange hues saturate them. The popularity of studio photography in India, as the British Empire in the late nineteenth century ushered in, reconfirmed the making of identities—inherited and acquired—in the closed, orchestrated setting of physical space. To complicate the binaries between settler and native, Waswo X Waswo through the act of studio photography conjures a world peppered with satirical humour. The series of hand-painted digital photographs A Visitor to the Court, composed in the courtly city of Udaipur, Rajasthan, is a labour of collaboration mutually shared by miniature painters R. Vijay and Dalpat Jingar, the third-generation photo hand-colouring artist Rajesh Soni, and the painter of golden borders, Shankar Kumawat, only to reimagine the intimacies developed within the contours of the atelier.

The two-day symposium (4–5 September, Ballroom, Bikaner House) What Future Hides Writing Critically In/For a Changing Nation is a continuation of TAKE on Writing Series – a brainchild of Bhavna Kakar to fill the gap of critical writing within the discipline Indian arts. The symposium conceptualised by Premjish Achari serves as a crucial part of the DCAW outreach programme. It features panel discussions and roundtables with art writers, academicians, curators, translators and practitioners to assess and inquire about the diverse forms of critical writing practices in art, fiction and translation. The symposium, organised in collaboration with the JCB Literature Foundation and The Raza Foundation, opened many collaborative possibilities to learn and unlearn from the shifts in critical writing as it is experienced and witnessed in India. Premjish Achari explains in his concept note that “The symposium is designed to find answers collectively to many crucial questions at a critical juncture in the wake of a hostile cultural climate, such as: How do we write critically in/for a changing nation? What are the newer forms of writing and strategies of dissemination used by writers and practitioners? What is the relevance of criticism in this changing cultural and political landscape? How do we create an intersectional approach towards criticality? Do we maintain the correct distance or work with the institutions to engender a praxis of institutional critique?”

Lately, with the rise of vernacular literature, the experiment in “typography and illustration and social media” has come into force, which has directly paved the way for new forms of writing. Correspondingly, the demand for regional texts in translation has garnered interest towards the expansion of the conventional definition of literature. Against the Western notion of print literature, Indian literature has been approached with interdisciplinary understanding rooted in oral, performance and visual studies. On the first day of the symposium, a spectrum of conversation and discussion attempted to blur these binaries between national and regional distinctions. Whether art practice and criticism are two sides of the same coin or otherwise—a tension that has long gripped the discipline of Indian art and aesthetics. The practitioners and critics, engaged in a roundtable discussion on the first day of the symposium, gauged how the two tenets overlap and stand in contrast to each other.

On the second day, the discussion revolved around the birth of new models of dissemination and reception of the writing practice. As the digital platforms reached unprecedented heights, the writing style underwent a significant change. If these platforms facilitate freedom to write and express an opinion, they also hint at the looming threat of censorship. The conversations saw the acts of writing and reading in a “changing nation” as the strategic tools for critiquing the sociopolitical inequality prevalent in the post-truth era. The roundtable discussion around art history and storytelling was a fitting end to the two-day symposium. The art history of the Indian subcontinent has been a site where the politics of exclusion and diversity have regularly come to play. The discipline that brews from the intersection between class, gender and politics demonstrates the necessity to speak truth to power. The discussants of the roundtable underlined how the proliferation of academic scholarship on art history has countered the epistemic violence committed in the hands of colonisers, class hegemony and gender oppressors alike. The symposium catered to the full house for two consecutive days to spearhead the much-needed arguments, debates, propositions, and possibilities around the multifocal discipline of art writing when the nation is constantly in the making.

Extending Binswanger’s play on alliteration in the title of the book by adding the term ‘momentary’ to the series of ‘m’ (money, magic, modern), one could flippantly reflect on the exhibition experience and the purpose of art. The works put on display by the seven galleries participate in the act of putting Indian art on the global map. Delhi, as a city, embodies the plural identity and diverse cultural bearings that anchor promising conditions for a fertile site that nurtures the many meanings of art in the absence of the artist and viewer’s singular hegemony. As a result, the many hierarchies that outline the binary between high art and profane, centre and periphery, dominant and marginal, elite and popular are diluted by artistic practice and viewer perspective. The long-sustained investment in the magic of the arts during the fifth edition of the DCAW has successfully set the histories of circulation in the field of the arts in motion. Towards this end, the DCAW squared away the righteousness of highbrow art to expand the sphere of inclusion—populated by artists, curators, collectors, curiositors, investors, patrons and viewers.

Delhi Contemporary Art Week 2022, Bikaner House, New Delhi, 1-7 September, 2022.