“Our sense of space results from our ability to move. Our sense of time, meanwhile, is due to being biological individuals undergoing distinct and changes states. Time is thus nothing other than the flow of change.”

Flights, Olga Tokarczuk

“…from the safety provided by the circulating references that cascade through a great number of transformations and translations, modifying and constraining the speech acts of many humans over which no one has any durable control.”

Pandora’s Hope: Essays on The Reality of Science Studies, Bruno Latour

The flow of change measured on a quantifiable scale of progress serves as the affirmative score of success. The inevitable circuit of progress created by the liberal forces plays into structural class domination, and turns a deaf ear to the social, political, and economic conditional events of everyday circumstances. The point to access the edifice of synchronised history presupposes the achievements gained via a chain of hierarchy rather than the pattern of equal distribution. The break in the historicity of time suspends the dominion of assumptions as a means to remove the patina of homogeneity from the power struggles. Here, the questions around the existence of life seem only to reinscribe the notion of survival of the fittest. The fourth episode of the 3-year-long project Does the Blue Sky Lie: Testimonies of Air’s Toxicities is a staged hearing titled In the matter Re: Rights of Nature. Conceived by Khoj International Artists’ Association and Zuleikha Chaudhari, in collaboration with lawyer Harish Mehla, the hearing leads an inquiry into the suspended histories of agrarian communities and the environment from the naturalist and socio-economic standpoints. Presented in the format of a case before the National Green Tribunal (NGT), the premise of the fictional case is two-fold: the petitioners (Khoj, Chaudhari and Maya Anandan – a minor) charge the Union of India through the Ministry of Environment, the respective state stakeholders and a fictitious farmers’ union to impose prohibition and penalties for stubble burning; and to assimilate a ‘Rights to Nature’ within Article 21 ‘Right to Life’ of the Constitution of India.

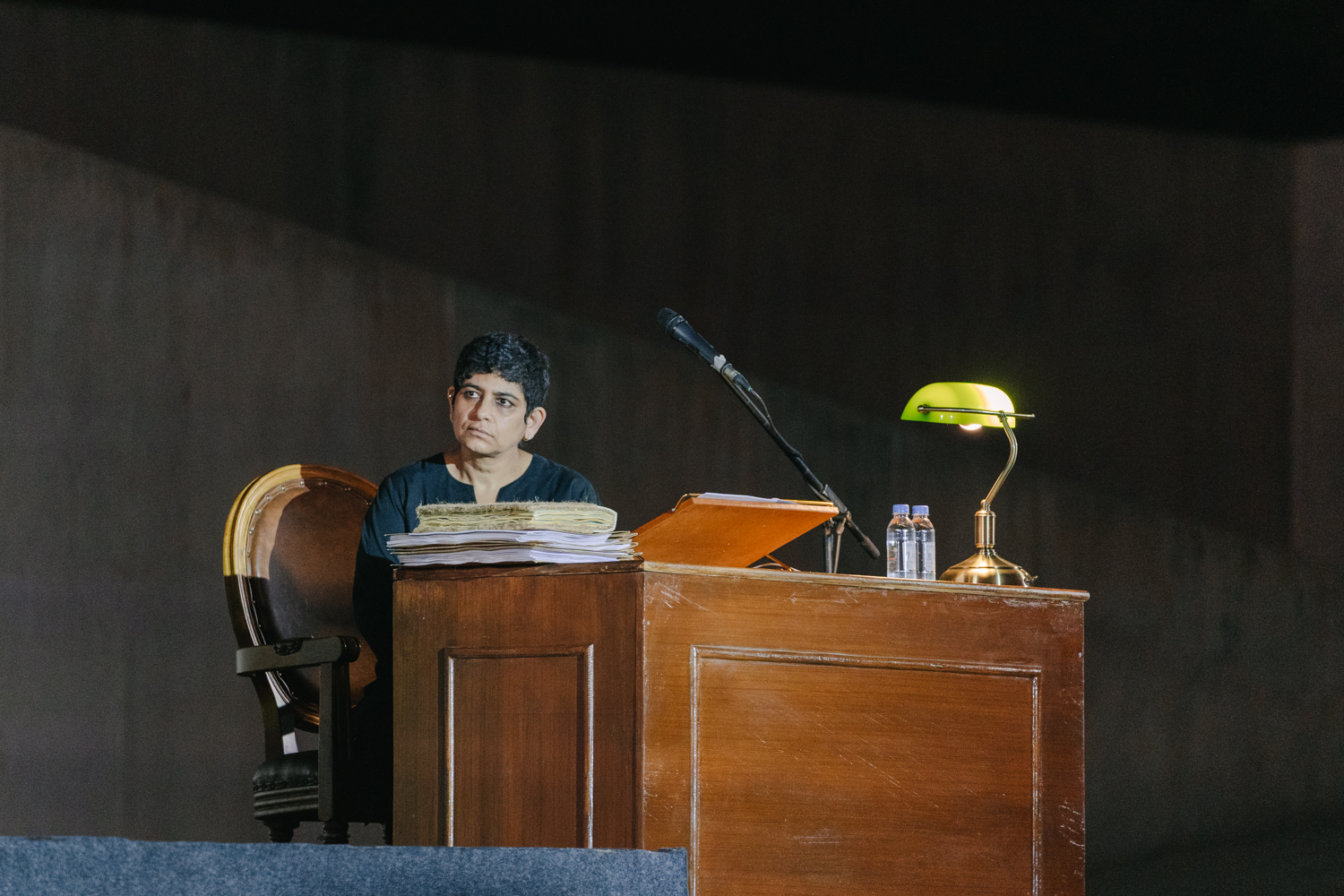

Court Master: Zuleikha Chaudhari. ‘In the matter Re: Rights of Nature’. Photo Credit: Alina Tiphagne / Khoj International Artists Association.

In the face of excruciating ecological imbalance, the advent of the Anthropocene calibrates the imperious power narratives to strip the dignity of humans as citizens, against the declining climate conditions at large. To recognize and oppose the detrimental effect of climate variability, the artist community finds recourse to fiction, a fragment of the broken time (Eze, Emmanuel), to disrupt the congruence of official history. Towards this end, the fictional case – involving three practising lawyers (Harish Mehla, Mannat Anand and Manmohan Lal Sarin), three subject expert witnesses (Manish Shrivastava, Tarini Mehta and Kahan Singh Pannu), three retired judges (Rajive Bhalla, Kamaljit Singh Garewal and K. Kannan) and three artists witnesses (Shweta Bhattad, Thukral & Tagra and Randeep Maddoke) – interrogates the palpable supremacy of man over the ones rendered invisible – marginalised groups and ecology. The collection of testimonies shared by lawyers, artists and experts lends a critical lens through which we – the witness – view the multivariate truths and explore the fluidity of meaning to better articulate diverse experiences.

Artist Witness: Shweta Bhattad. ‘In the matter Re: Rights of Nature’. Photo Credit: Alina Tiphagne / Khoj International Artists Association

From the vantage point of fragmented temporal spaces, Chaudhari – bearing the role of court master and leading the direction and dramaturgy of the staged hearing – opens to the public witnessing a slew of silence in the mainstream data. Known to incessantly dovetail the prominences of performance in the field of law, Chaudhari excavates the duties listed in the Constitution of India under Article 48A: The state shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forest and wildlife of the country; Article 51A: “Protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife and to have compassion for living creatures”; Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court declaration to protect ‘Mother Nature’ as a ‘living being’ in 2022, amongst others. All activated to transpire an “agentive quality of documents” (Trundle and Kaplonski) and expand the scope of the Right to Life listed in Article 21 from human life to the environment and the rest of the species. Additionally, it states, to which counsel representing the Union of India through the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Anand draws our attention to how Article 21 has held that “the right to clean environment is a fundamental right.”

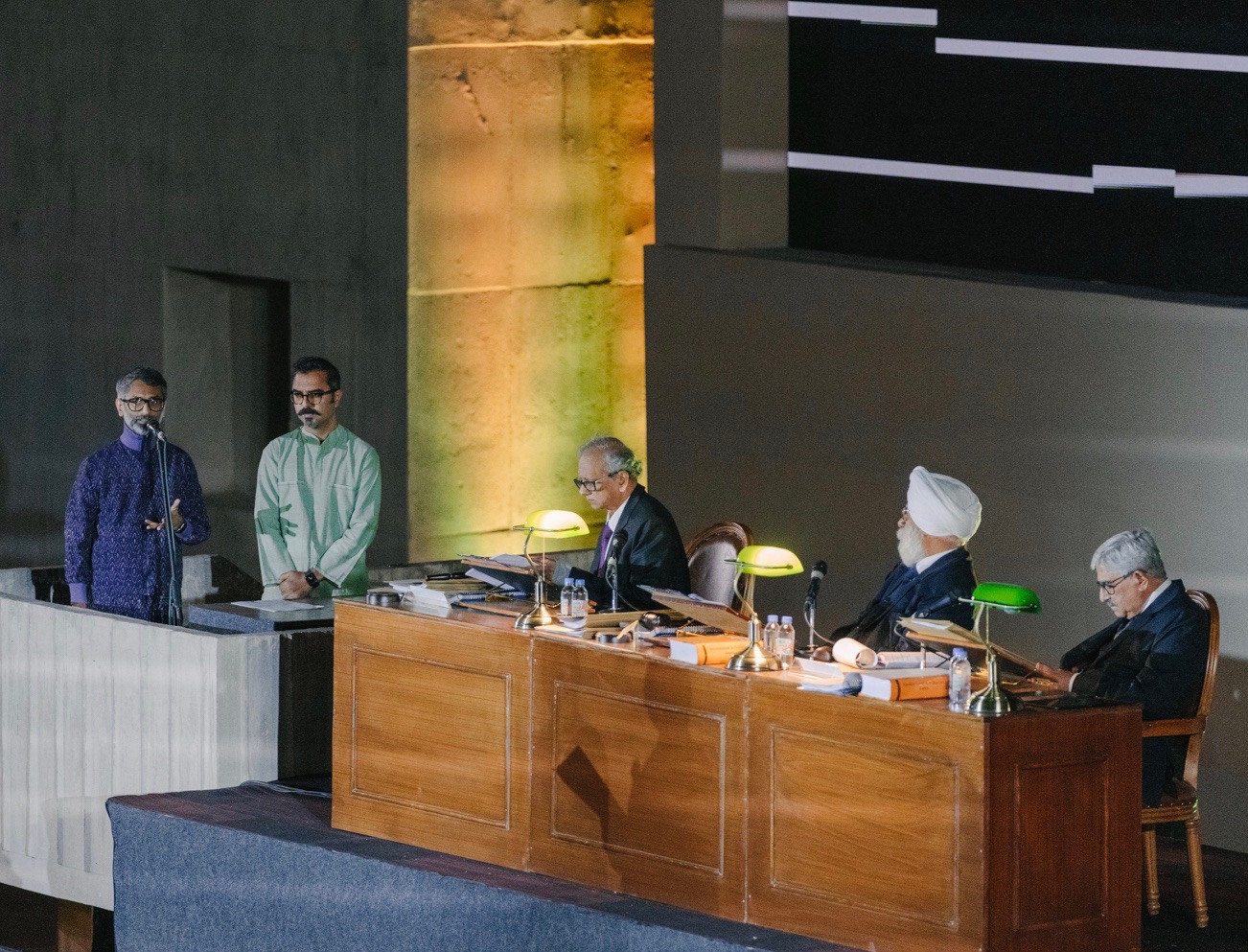

Artist Witness: Thukral & Tagra. ‘In the matter Re: Rights of Nature’. Photo Credit: Alina Tiphagne / Khoj International Artists Association

Latour devised the concept of “circulating reference” which entrenches the materiality of the object with language. It debunks the presence of the chasm between the object and language and suggests a persistent chain-like translation across the two. The manifestation of the historical record into the power of language is determined by an “old settlement” amongst language and world. In other words, it illustrates how to “pack the world into words”, and subsequently to the objects. To a similar effect, the material and materiality of the objects presented by the artists-witnesses are dubbed as the site of knowledge production (Riles). The material and materiality gravitate towards the interdisciplinary perspective to ascertain the accessibility to the muffled voices, otherwise lost in the convoluted noise of liberal narratives. For instance: Shweta Bhattad, founder of the collective space ‘Gram Art Project’, stands in the witness box while wearing an organic apron. The materiality of the apron and Eaten Cotton, a cookbook epitomise the inherited intergenerational knowledge about mixed-cropping to shed a spotlight on socio-economic practices rooted in the coexistence of human and nature devoid of conflict. The traditional methods of farming performed in Paradsinga, Madhya Pradesh, from where Bhattad hails, transmutes to be an alternative site-specific example of a flourishing way of cropping.

Mehla, the counsel representing the petitioner, argues that the salient features of sustainable development remain a step away from their full realisation unless the epoch of Anthropocene is not switched with the Ecocentric approach. Crucial to the declining health of nature is the incessant stubble burning in Punjab and Haryana during October and November. Consequently, poor AQI levels affect every species. Even if the laws to maintain the ecological balance exist, as argued by Anand, the efficiency of their implementation at the grass root level is subject of dispute, says the expert witness Tarini Mehta. The complexity of stubble burning is a reflection of the urban-rural divide in India, according to Lal Sarin, representing the Farmers’ Union, where the economic needs of the former have severed the relationship with the latter. Shrivastava elaborates on the relationship between the economy and environment. He cites the research titled Limits to Growth propounded by the Club of Rome, a group of scientists, who looked for equal distribution of resources within the planetary boundaries. The model of sustainable development demands due engagement with the local community to understand the limits of production and the mindful use of resources.

Artist Witness: Randeep Maddoke. ‘In the matter Re: Rights of Nature’. Photo Credit: Alina Tiphagne / Khoj International Artists Association

Working closely with the community of farmers in the state of Punjab, the artist-duo Thukral & Tagra have developed a game titled Weeping Farmers to let the players familiarise themselves with terms such as debt, loss and suicide. The game stems from data mapping of the farmers, and shines a light on the soaring number of suicides committed by women. Every forty minutes, a farmer dies in the game. The hyphenated identity of the duo the artists and citizens amplify the experiential response to the dire state of affairs, in the hope that Weeping Farmers could serve as a social repair. A documentary film titled The Landless by Randeep Maddoke encapsulates the intersectional complexity of the situation in which the community of farmers finds itself embroiled. More often than not, an outsider misapprehends the predicament of a farmer as a momentary crisis, and mistakes him to be the owner of the land. The Landless opens the world of a farmer in Punjab – effectively an indentured labourer – who ploughs the field, and sows and reaps the crop for a landowner. The situation is aggravated when the landless farmer belongs to a Dalit community. Caught within the web of caste-based discrimination, this pushes them even more surely into the claws of economic exploitation. Despair forces many to commit suicide. At the onset of the Green Revolution, the exigency to grow paddy crop rice rather than what was native to the land of Punjab exacerbated the living condition of landless farmers, constituting 70 percent are Dalits. During the staged hearing, Maddoke runs a scene from the documentary populated by two landless farmers having tea while talking about the dire effects of pesticides, used for paddy crops, on the reproductive systems of the goats. The vicious circle of production and distribution to maintain the profits of industry refrains from changing the social position of the lowest denominator of society.

Pannu questions the rhetoric of the catchphrase “Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas” which calls for community action for wider developments. But the expert asks what constitutes the whole of the fraternity when the Dalits are ostracised from the centre. The criminalization of the farmers who engage in stubble burning is the failure of the State to admit the limitation of the alternative to the practice. The issue of stubble burning is a cog in the wheel – the wheel put into motion by rich conglomerates such as real estate owners, oil factories, and automobile manufacturer companies – succinctly mentioned by Justice K. Kannan. The criminalization of farmers is misplaced since stubble burning contributes to 17% of air pollution. Under the umbrella of development, the restricted availability of economically viable options for the farmers exponentially increases the monetary value of the corporations. Pannu mentions at the height of the Green Revolution movement that state-run media channels on television promoted the stubble burning. The impasse and embitterment encountered by the farmers is a corollary of the inclination of multivariate fronts to be incognizant of their vulnerability.

The staged hearing in session – ‘In the matter Re: Rights of Nature’. Photo Credit: Alina Tiphagne / Khoj International Artists Association

Removed from the boundaries of the conventional court hearing in the closed room, In the matter Re: Rights of Nature enacted under the magnanimous Open Hand Monument, designed by the architect Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, furthers its symbolic gesture to “the hand to give and the hand to take; peace and prosperity”. The historicity of the performance acutely suggests that harmony and reconciliation cannot be achieved without a panoptic perspective that encompasses the legal texts, material and materiality, as well as political concerns. The linguistic plurality endorsed by the witnesses, as an extension of walking the audience through the diversity of opinions on the matter of subject, accentuates the necessity of collective action from all quarters of life. The improvised wit of the staged hearing rather stems from the acknowledgement of the long struggle for the promised land of justice. Even though the Stockholm Declaration, the first international document to recognize the right to a healthy environment came into force in 1972, the rising statistics of people being forcibly displaced by climate change is alarming. In light of there being no easy fix, the final judgement rules out the option of a permanent stop to stubble burning to protect the environment. Acting upon the need of the hour, the three judges unanimously conclude that the Right to Life is no more limited to the protection of the aura around the ontological phenomenon of human existence. The extent to which Right to Life is extended seems to argue for the sustained dignity of the Rights to Nature as well.

As Chaudhari requests all the witnesses to state their credentials before the court, she addresses the importance of responsibility as citizens to map the indispensability of their evidence in the court hearing. Bertolt Brecht mentioned, “Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it.” The metaphor of a ‘hammer’ fits well in the staged hearing when the audience remained seated to the unfolding of multi-layered narratives spun around the empirical evidence and environmental issues for close to three hours. Making the presence of ceremonial gavel on the court tables unnecessary. The success of In the Matter Re: Rights of Nature lies in the subtlety with which the audience is cajoled to sow the seeds of sensitivity to narrow the Cartesian boundaries of nature and culture.

The staged hearing In the matter Re: Rights of Nature was performed at the Open Hand Monument, Chandigarh on March 5, 2023.

References:

- Eze, Emmanuel Chukwudi. On Reason: Rationality in a World of Cultural Conflict and Racism. London: Duke University Press, 2008.

- Latour, Bruno. The Making of Law: An Ethnography of the Conseil d’Etat, trans. Marina Brilman and Alain Pottage. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009.

- Riles, Annelise. Documents: Artifacts of Modern Knowledge. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

- Tokarczuk, Olga. Flights. New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2018.