Walking down the staircase into the underground exhibition space of Gallery Espace, New Delhi one finds oneself venturing into a world where pneumatophores emerge from the saline, sedimented soil of mangroves; where traces of a lost Nawabi menagerie activate the viewers’ perception of belonging and becoming; where an intricate hand embroidered image of the Palace of Porcelain merges into the background of soft muslin in a similar manner in which thriving ink drawings of wetland birds camouflages into the ground of jute rope and rice paper pulp. The world of Sengupta’s most recent set of prints, textiles, paper pulp works and animation envelop viewers in its folds and evokes multisensory responses. Permeabale as the pneumatophores of the Sunderbans, the project has steadily and gradually developed over the last two years. The “river of unrest”—as the river Ganges manifests in this project, plays a crucial role in Sengupta’s deeply committed research based practice; her field trips along the river finds expression into her archival studies and hands on practice in the city of Calcutta or the present-day Kolkata, nurtured by the river.

In many ways, Sengupta’s project is situated between “a river of unrest” and “a delta of dreams.” It is the silent space that occupies the void between evidences, oral narratives, sensory experiences, memory and creative reconstructions. Calcutta and its colonial history have been addressed in her art projects the last two decades offering an unique perspective to assess and apprecitate the city’s entanglement of past and the present. In this recent project, Matiaburj (in which mati indicates clay/mud, and burj implies tower) in south west of Calcutta by the river remains a key site where authoritarian and local histories juxtapose, where fiction-like facts makes way for Sengupta’s ambitious creative reimaginations. With a mindful selection of historically informed materials, that include inherited and constructed textiles, jute fibre, paper pulp and graphic prints, archival history is brought in a dialogue with sensorial experiences.

Arguably the key contribution of this project is its emphasis on the cultural and political histories of lands that are largely uninhabited by humans, such as the dense mangrove forest of southern Bengal. The muddy river banks of this region, especially in the Sunderbans, deceive the traces of its cultural and political pasts in ways they conceal predator reptiles and visiting birds. The simultaneity of concealing and revealing, in the Mangroves and in Sengupta’s works, facilitates meditation upon an essential characetristic of art. A comparison or rather a correlation between the outer “world of phenomena” and “the inner world of sense,” in Hegelian thoughts, translates into the process in which art assumes a mode of appearance that can be termed as deception.[i] Far from concluding this as a simplistic relationship between “appearence” and “essence,” art can be perceived as the paradoxical unity of the material and the transcendental.[ii] This dialectical component manifests in Sengupta’s material process and intellectual commitment.

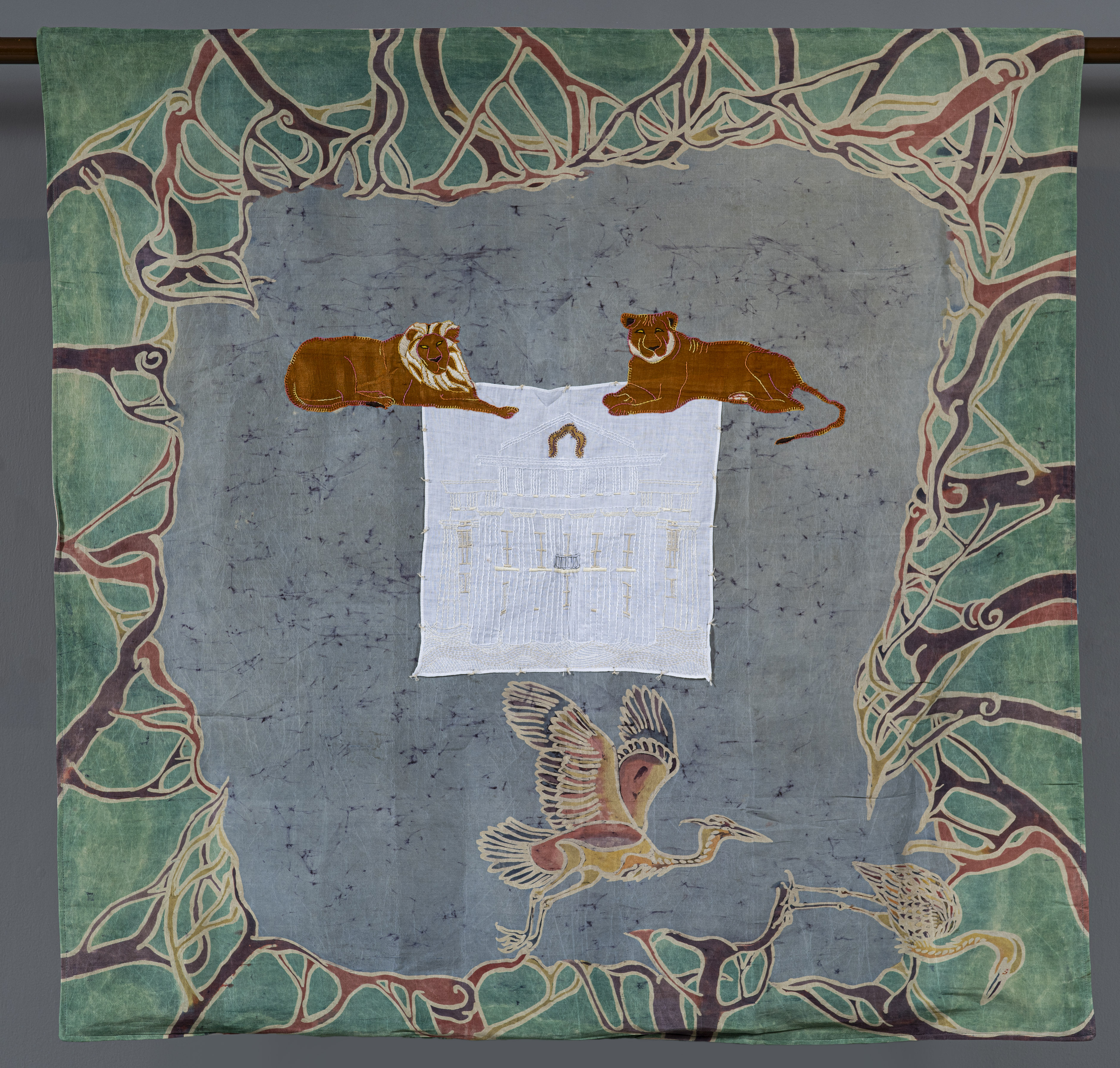

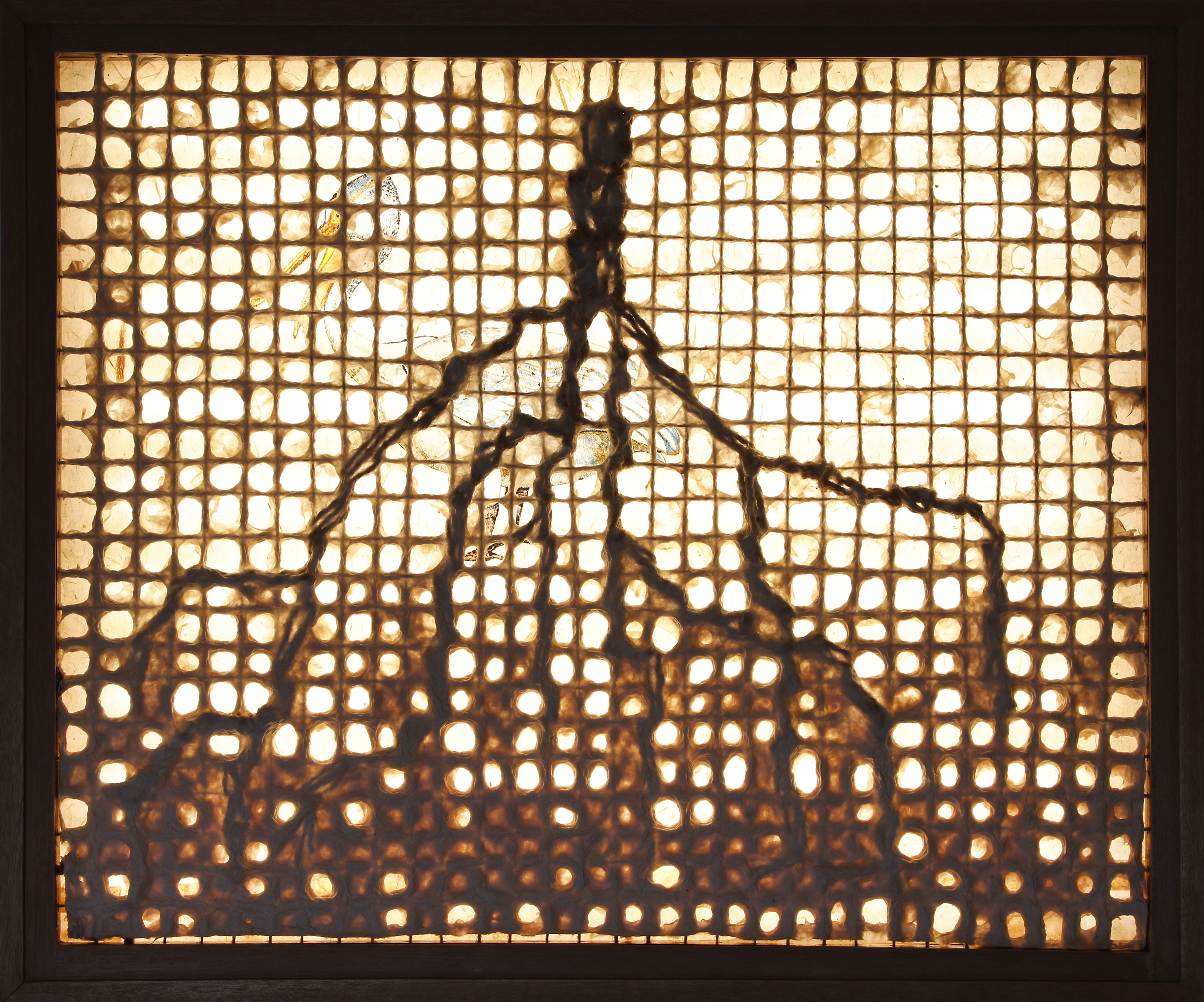

In the process of making Shadows on the estuary – II, a series of jute ropes are intersected in grid pattern within a rectangular wooden frame. Additional pieces of ropes are tied simulating the forms of the pneumataphores. Then, the frame was dipped in a vat of rice paper pulp. The rice pulp, organic as sedimented river clay, hardened over the grid and disrupted the evenness. This frame was then placed above a backlit sensuous ink drawing of a Pelican on rice paper. The sinuous lines on the fibrous rice paper, partially visible through the perforated uneven jali formation of jute rope and lumps of paper pulp, evokes a sense of camouflaging in nature. However, when put in perspective with the larger body of her works, the seemingly deceiving nature appears as a connecting thread between culture and environment. As viewers approach close to Matiya Burj – Tower of Mud II, the central white muslin kerchief reveals a mansion, embroidered in white thread drawing upon historically informed chikankari (a specialised embroidery technique from Awadh, especially Lucknow); otherwise, from distance, the palace convincingly camouflages into the background. Sengupta traces back a curious narrative about the nawab-in-exile Wajid Ali Shah and the journey of his menagerie to Calcutta from Lucknow through the riverine route and the consequent dispersal of animals. The great banyan tree of the Botanical Garden (presently A. J. C. Bose Indian Botanical Garden) across river Ganges from Matia Burj, which evidenced this unforeseen displacement of people, animals and political power, encircles the picture plane. Meandering through historical narratives enables her to reflect upon human interventions in relocating antilopes in the Sunderbans to support the growh of predators. Playfully yet intelligibly, Sengupta turns her archival research, photographic records and field visits into a transformative tale of paradoxes.

The riverine networks of Bengal (both West Bengal and Bangladesh) runs as underground tributaries to Sengupta’s exploration of shared culture, cuisine, trauma and partition history in the past. Her most recent project explores river as a motif that flows from archival accounts to dreams. The mud-like surface of Ebb on the estuary – II featuring bold, backlit and negative image of Tiger palm leaves stimulates a visceral experience of the dampness of the river banks; whereas braided and knotted jute fibre springing out of the pulp surface reminds the viewers of the association of economic and trading activites around jute and hay in lower Bengal. In the recent years, the pressing environmental concerns around us are addressed in a variety of visual and audio-visual expressions. Whereas the critical discussions on ecology and environment emphasise carbon footprint and even the production, transportation and display of artworks in exhibition spaces,[iii] the interrelations of so-called nature and built environment remain largely under theorised. It results into an unesy silence between the perceptions of cultural environment and forests/National Parks. To propose a creative reimagination of this gap, the transformative potentials of art making is perhaps crucial. Sengupta’s artistic process, like a river, flows through this gap and presents us with the dreams of more nuanced, innovative correlations between our surroundings and us.

[i] G. W. F. Hegel, “The Range of Aesthetic Defined, and Some Objections against the Philosophy of Art Refuted,” in Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics, trans. Bernard Bosanquet (London and New York: Penguin Books, 1993), 10.

[ii] Walter Benjamin, “Allegory and Trauerspiel,” in The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne (London and New York: Verso, 1977), 160.

[iii] T. J. Demos, “The Politics of Sustainability: Contemporary Art and Ecology, ” in Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet 1969–2009, ed. Francesco Manacorda (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 2009), 19-20.