Benode Behari Mukherjee and his more than Oriental Splendor (Introduction Text)

Whatever happened to the Bengal School? There is an extensive literature devoted to the development and apex of Orientalist art movement, which began around the turn of the last century and stretched into the 1920s, but very little significant analysis of how the movement “petered out” and why. But peter out it did-according to the leading art scholars whose work focuses on the movement. As Tapati Guha-Thakurta writes: “As formulae replaced formulae, what began as a ‘movement,’ a creative urge towards change and a new identity, folded inwards into a ‘school’, stagnation even as it reached its peak of success.”1 By the time Rabindranath Tagore officially established the arts department at Santiniketan in 1921, the movement was arguably already losing steam.

While Santiniketan became one of the finest art colleges in India, it never was able to perpetuate the dynamism of Orientalism’s grand vision. The art historical canon tells the story of a subsequent dissipation of not only the Bengal school’s energies, but also their primary members. One exception is the artist Benode Behari Mukherjee, who not only studied as a young student under Nandalal Bose at Santi niketan, but also spent his final days teaching at the institution. He was not, however, unaware of the school’s aura of veneration-even from his earliest days. As he rather poetically put it:

Rabindranath tolerated many things for many reasons. He did not weed out by force the things he did not want, or was unable to. So one can see how his interest in Visva-Bharati decreased with time. And weeds that had taken root in the shadow of disinterest grew up to be giant trees after his death.2

Mukherjee is a paramount figure through which to trace the legacy of the Bengal school through the hazy period of it’s alleged decline in the mid 20th century. He was born in 1904, one year before Abanindranath completed his infamous Swadeshi image Bharat Mata. As a student at Santiniketan, Mukherjee had close contact with Abanindranath Tagore, Rabindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose, and would have had an intimate understanding of the ideology behind Orientalist art. Unlike many of his peers, however, his life could be seen as a series of returns to Santiniketan. Though he travelled widely, as we will see, he never ultimately shifted his allegiance. Hence, Mukherjee’s life provides a perfect bridge from the period when the Bengal school was at its zenith in the artist’s youth to the mid-century when national and international focus seemed to shift away from Bengal and south towards the Bombay Progressives.

Mukherjee was a significant and well-respected artist in his own right despite the nation’s wandering interest in the movement that produced him. Appearing in this issue of TAKE alongside this essay is a piece written by Mukherjee’s friend and colleague K. G. Subramanyan in 1969 on the occasion of a retrospective of Mukherjee’s work organised by the International Cultural Center and held at the Rabindra Bhavan in Delhi. It begins: Benode Behari Mukherjee stands a little apart from most of his contemporaries on the Indian scene. When other Indian artists are torn between the conflicting attractions of the East and the West he is, gracefully, an artist without a dilemma. Although he grew up together with the artists of the so-called Bengal school his work is astonishingly devoid of their unctuous sentimentalism. When most Indian landscape painters painted the Indian scene in the broad generalities of European academic and neo-impressionist modes he painted it in an intimate calligraphic idiom reminiscent of the Far East but modified to suit its textural luxuriance and variety. When most Indian artists were involved exclusively with easel or miniature painting he explored the dimensions of screen, scroll, and mural; when they tended to be professional purists out of contact with their environment he emphasised the continuities of Indian art through its various hierarchies. So, he does not fall easily into the usual classifications Indian art critics are fond of.3

Mukherjee was also an avid writer. He lost what was left of his faltering eyesight after a botched operation in 1957, but rather than wither in inactivity he began to pen prolifically about his thoughts on art and life to the great benefit of later art scholars. Wasting no time, he completed four essays the same year that his blindness occurred. This essay will draw on two of those works. The first, Chitrakar, offers a biographical narrative of the artist’s life and work, while the other, Silpa Jignasa, explicates the artist’s more theoretical musings on the nature of art on a horizon of shifting cultural contexts. Both essays were translated by Subramanyan in the late seventies, and published in the well-known Bengali literary journal Ekhon. Following Mukherjee’s sudden death, these essays, along with two others also translated by Subramanyan, were collected in a book Chitrakar and published in 1979.

Beyond the significance of Mukherjee’s biography and individual import as an artist, I was compelled to select him as the object of my essay because his life and oeuvre represent the extension of one of the Bengal school’s most distinctive attributes: the impulse to look east for inspiration. Much has been made about the “revivalist” tendency of the Bengal school. Indeed, the fact that early giants of the movement such as Abanindranath and Havell laid so much emphasis on the “re-discovery” of India’s ancient past was to have far-reaching consequences for the trajectory of Indian art in the century to come. However, the Bengal school’s exchange of both artists and ideas with Japan was unprecedented. It was this legacy that most clearly influenced the development of Mukherjee’s personal style as his work clearly evinces a rigorous commitment to East Asian ink painting techniques. Moreover, he spent a significant period of his life studying and teaching both in Nepal and Japan.

Mukherjee first visited Tokyo in 1937 when he was thirty four years old and already part of the teaching staff at Santiniketan. As he wrote: “I had gone there to make personal contacts with Japanese artists and understand the inner spirit of Japanese art.”4 The description of his travels that follow is rich with sensual details and personal anecdotes. It is clear that the focus of his travels were the individual artist mentors he befriended, such as his “guide” Hango with whom he corresponded until 1950. As Mukherjee recalls, Hango not only brought him to exhibitions around the city and introduced him to respected artists, but also took pains to expose him to some of the darker and more opaque aspects of Japanese society, such as the plight of urban poverty exacerbated by the national prohibition of public panhandling. Mukherjee took care to flesh out the political realities of the time, not least of which was the imminent onset of World War II. The art, practice, and ideology he encountered in Japan were by no means removed from this greater cultural context. In fact, ink painting was increasingly burdened by the overtones of Japanese nationalism and isolated from foreign artistic influence.

Mukherjee was not particularly interested in this hermetic nationalist ideal. In fact, he is very clear that politics, Indian or Japanese, held little interest for him at all. He describes how he grew up at the time of the Swadeshi movement and took part in many of its rituals—such as the smoking of bidis and the wearing of homespun, but “I could not relate myself with any of these too closely, nor do any paintings based on them.” Instead, he tended to be interested in more intimate and everyday subjects such as nature and the local landscapes. This set him apart from many of his peers who tended to take up Indian myths that were suited towards contemporary allegory.

Many of the Japanese artists he encountered were disdainful of the Chinese tradition and invested in a “pure” form of national expression that did not borrow from mainland styles. Predictably, Mukherjee was drawn to the less dogmatic artists who were not so wary of such hybridity. It is clear from his writing that it was, in fact, the mixing of styles and influences that excited him most. He wrote:

The Japanese artists (of that time) were influenced greatly by the Impressionists. They had also absorbed well the lessons of Matisse. A large number of Paris-returned Japanese were also trying to review and analyse their country’s traditions. Surrealism had just then raised its head in Tokyo; it had not yet been fully grasped by the Japanese artists.5

Mukherjee was not satisfied merely to travel widely and study the painting techniques of Far East. Rather, he followed closely in the footsteps of his Bengal school forbearers with a significant attempt to theorise the development of Indian art in the broader context of both Asia and the world at large. The bulk of these aesthetic musings can be found in the long essay Silpa Jignasa, which presents Mukherjee’s wide-ranging meditations on everything from sexuality to computers. What interests me in this essay, however, are specifically the artist’s views on the essential characteristics of Eastern Art. Mukherjee writes:

All Eastern traditions follow the path of subjective experience; conversely, from the time of the Renaissance, European artists follow the path of objective vision. They have discovered the world of forms in colour and light. Let me elucidate this with examples.

Some Bengali scholars asked a patua6 to draw a motor car to find out how observant he was. The patua asked for time-to grasp the subject by contemplation. Then, he made a drawing of the motorcar leaving out many details, though not the headlights, the steering wheel and the mudguard. The learned scholars noticed that the details left out were such as could not be ‘transformed’ in the work.’ The image the patua made was that of a dynamic vehicle which resembled the motorcar but was not its exact copy.

If the same request was made to a trained modern artist, he would have, too, liked to have a good look at the thing but in this looking he would not have left out any detail. Broadly, this is the difference between the Eastern and the Western viewpoints.7

As the rest of his essay helps to clarify, Mukherjee defines the artistic traditions of the East as somehow capturing the rhythm or feeling of a subject as opposed to Western artistic traditions that since the Renaissance have striven for a more objective, physical likeness. Hence, the patua paints only the details necessary to suggest the character of the car while the “modern” (we may presume academic) painter makes a point to reproduce each detail in a scientific manner.

Mukherjee goes to great lengths to demonstrate this distinction with numerous examples drawn from his knowledge of Indian, European, East Asian, and even American art. We can see that this argument has much in common with earlier discussions that similarly essentialise an East/West dichotomy. In particular, I’m thinking of the writing of Havell, Abanindranath, Sister Nivedita, Okakura, and Coomaraswamy (among others) who all claimed that Bhava, or feeling, was the unifying characteristic that set Indian and Asian art apart from the art of the West. While Subramanyan never uses the word bhava or even “feeling” in his translation of Silpa Jignasa, there is a definite similarly between Mukherjee’s notion of Asian’s non-analytical approach to art and the older generation’s emphasis on bhava.

However, there is one very significant step in Mukherjee’s argument that sets him apart from the early Orientalist cannon. He does not ground this special Asian artistic sensibility in spirituality or religion. I argue that it is this fundamental difference that allows his unique interpretation of the Orientalist legacy to meet with success in the midcentury.

Each of the proponents of the Oriental art movement was clear that it was specifically the spiritual impulse that unified Eastern art and gave it power. Okakura’s book The Ideals of the East, from 1904, famously begins:

Asia is one. The Himalayas divide, only to accentuate, two mighty civilisations, the Chinese with its communism of Confucius, and the Indian with its individualism of the Vedas. But not even the snowy barriers can interrupt for one moment that broad expanse of love from the Ultimate and the Universal, which is the common thought-inheritance of every Asiatic race, enabling them to produce all the great religions of the world, and distinguishing them from those maritime peoples of the Mediterranean and the Baltic, who love to dwell on the particular, and to search out the means, not the end, of life.8

This sentiment is echoed not only by Abanindranath and Havell, but also with varying agendas and inflections, in the writing of the Anglo-Irish Swami Vivekananda disciple Sister Nivedita, and the renowned Ceylonese art theorist Ananda Coomaraswamy.

Yet Mukherjee makes in clear throughout his essay that he does not trace the uniqueness of Asian art to spirituality. He goes to great lengths to describe the secular artistic traditions of the east, remarking as if against his forbearers:

We have a small and admittedly very partial answer to the much larger question “What happened to the Bengal school?” Mukherjee is undoubtedly one of the primary inheritors of the movement to co-exist in the public eye with the ascendance of the Bombay “Moderns” following independence. Although much of his analysis of art history and theory derives from the perspectives of his forbearers, he has distanced himself from their dogmatic insistence on spirituality as the unifying characteristic of Asian art. This was, perhaps, a result of the changing attitude of the times. Let us remember how significant the general socio-political emphasis on strength through secularism would have been at the time of Independence. Moreover, as Karin Zitzewitz has argued, the Bombay “Moderns” were indeed unified by their radical secularism.9 However, Mukherjee did not look towards Western avant-garde practice as they did. Rather, his primary commitment was to the East. As Subramanyan’s essay makes clear, Mukherjee was celebrated as a sort of renegade pioneer, carrying on many of the central tenets of the Bengal school into a staunchly secular post-colonial environment.

I would like to close with a return to the present. It has been half a century since Mukherjee worked and wrote, and his place in the art historical canon has been secured. What is more interesting is how very prescient his unusual positioning in the art world appears today. The Far East is the new global avant-garde. Okakura was right that Asian unification would be the gateway to our shared aesthetic future, though he should have thought more in terms of biennales than Buddhist texts. Today’s Chinese contemporary super-stars are the most radical of secularists, going beyond the disinterested idealism of the Parisian or Bombay vanguard to actually celebrate capitalism and the disintegration of spirituality. It is perhaps not entirely wrong to suggest that some of the idealism of the original Orientalists is at work in this most anti-idealist of art practices, and that Mukherjee’s source of secular inspiration in the East was a significant if small step in this fraught and tangled lineage.

References

- T. Guha Takurta, The Making of a New‘Indian’ Art: Artists, aesthetics, and nationalism in Bengal, c. 1850-1920, pp. 314.

- B. Mukherjee, Chitrakar, pp. 42

- Subramayan, Benode Behari Mukherjee, pp. 73.

- B. Mukherjee, Chitrakar, pp. 36.

- B. Mukherjee, Chitrakar, pp. 36.

- Patua is the name for a particular group of folk artists in Bengal who paint narrative scrolls.

- B. Mukherjee, Silpa Jignasa, pp. 151-152.

- K. Okakura, The Ideals of the East, pp. 1.

- K. Zitzewitz, The Aesthetics of Secularism: Modern Art and Visual Culture in India.

K.G. Subramayan: Catalogue of Benode Mukherjee’s Retrospective

Rabindra Bhavan, New Delhi, 1969

Benode Behari Mukherjee stands a little apart from most of his contemporaries on the Indian scene. When other Indian artists are torn between the conflicting attractions of the East and West he is, gracefully, an artist without a dilemma.

Although he grew up together with the artists of the so-called Bengal school his work is astonishingly devoid of unctuous sentimentalism. When most Indian landscape painters painted the Indian scene in the broad generalities of European academic and neo-impressionist modes he painted it in an intimate calligraphic idiom reminiscent of the Far East but modified to suit its textural luxuriance and variety. When most Indian artists were involved exclusively with easel or miniature painting when explored the dimensions of screen, scroll and mural; when they tended to be professional purists out of contact with their environment he emphasised the continuities of Indian art through its hierarchies. So, he does not fall easily into the usual classifications Indian art critics are fond of.

What makes him an artist without a dilemma is probably the fact that instead of depending entirely on the conventional vocabularies of the East or the West, he started his work with a terminological search. Strangely enough, this can perhaps be attributed to his early interest in Far Eastern calligraphic painting Although linear calligraphy was not unusual in various forms of Indian art, from the hieratic to the folk, calligraphic painting of the Far Eastern type which involved a terminological equivalence of the tool mark and the visual image was something new altogether. The basic ingredients of such of work, if it had to be authentic and original, had to be evolved afresh in each new situation; which is another way of saying-to paint the gaudy ‘palas’ and ‘simul’ and the delicate ‘landlotus,’ in the sun-drenched landscape of the Bengal countryside, the conventions used to paint the pine, the bamboo and the peony against the misty mountain landscapes of China and Japan are hardly adequate-their terms have to be sought anew.

So Benodebabu embarked on such a search, beginning at the beginning. At the start he sought image equivalents to local flora and fauna—flower and leaf, bush and tree, man and animal, the basic alphabets of the organic scene. Then he sought the means to unfold with these the Bengal landscape, the flat and austere landscape of Birbhum in particular. He sought to play the bareness of its fields against the richness of its copses; he put character into its turf and its trees and made them individual. The lush ‘jamun’ tree stood demure in its cloak of leaf beside shapely leaf; the bare ‘siris’ listlessly shook its seedpods against a tattered summer sky; the scraggy date-palm gesticulated in its loneliness – all like characters in a mime, quiet but unforgettable, caught together in a very specific emotional web. His landscapes are for this reason some of the most original in modern India and some of the most moving; they are sad, lyrical, and poignant by turns, without any attempt at violent drama. On the other hand, they have very little colour, work within a closed range of tonalities and are sometimes diaphanously non-material.

From single landscapes bristling with calligraphic niceties Benodebabu went into screen and scroll painting. These had new dimensions to them they unfolded slowly from area to area of interest in a strange time-space relationship, affording to the onlooker great possibilities of visual perambulation. In these the descriptive vocabulary of Benodebabu’s calligraphic style increased in range and acuity; he had appropriate visual devices answering to every kind of formal and spatial nuance. He could now lead one’s eye with unerring ease from detail to detail, now to linger on a bush, now to scamper on a grass bank, now to belly crawl on uneven ground, surprising it, regaling it, drawing it into near-physical participation.

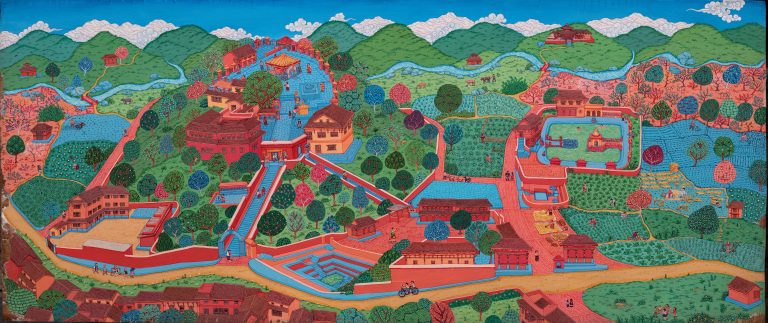

So, when Benodebabu started painting his murals he hand, already with him a very sophisticated arsenal of visual devices, A miraculous facility to populate an overall time-image with appropriate visual incidents and bring it alive with symbolic overtones makes his murals unique in the whole gamut of modern Indian painting. His first major mural on the ceiling of a dormitory in Kala Bhavana (Santiniketan) pieces up various views of Birbhum village life into related saga stretched out in time; people work, relax; play or ply their trades through the livelong day; the landscape undergoes metamorphoses from season to season, with trees flowering, bearing fruit, or standing naked to the skies. With a contraposition of various visual episodes and landscape details in tantalising perspectives he contrives to show the passage of time and its cyclic reversal. It is done in a restricted palette of reds, yellows, greens and whites against a background of russet and ochre, but the whole surface of the mural coruscates with visual surprises and a dynamic calligraphy of line.

In the course of the next ten years Benodebabu did two other major murals. One, in the attic of Cheenabhavana (Santiniketan), is an amusing visual chronicle of a day’s activity on the campus, poetic, humorous, using devices of visual hide and seek as in Japanese screen painting. The other, in Hindi Bhavana (also in Santiniketan) based on the lives of medieval Indian saints, is larger and more ambitious and can be said to be his magnum opus, as it exceeds the others in size, conceptual subtlety, range, and depth. It contrives the image of the growth of the Indian religious tradition through time by ranging the figurative life-dramas of the various saints as if they were successive stages in a growing river-from small beginnings in the mountain fastnesses the tradition swells and meanders through the plains, becoming more varied and populous, growing larger and deeper and more expansive before throwing itself finally on the ocean of mankind in the Indian villages. The descriptive incidents get smothered in a great sense of flux; the personalities lose identity in the stupendous human pageant; it is the portrait of a whole society in movement, an ageless and immemorial society, with an exasperating variety of culture and custom, in which there were no dividing lines between religion and life.

The murals usher Benodebabu into a new stage of work. Adept at dramatic assemblages of landscape and figure subjects, he shows even a greater sense of drama in his subsequent painting, done in Nepal, Mussoorie, and Patna; figures interpenetrate trees and architecture, in groups in processions, in work and play; the calligraphic elements get welded together in tight but ambivalent images; the linear structure is summary, and the colour washer are used with great economy and precision.

There is great variety and range in Benodababu’s calligraphic work. His early work has the crispness, economy and inevitability of Far Eastern calligraphy, redesigned to tackle Indian subject matter-to elaborate the meticulous foliage of an ‘amloki’ tree, to indicate the elastic strength and spikiness of the Indian date palm, or to show the lean pig and the midget goat against the dry ridgy Bengal countryside. Slowly his landscapes gain in colour and textural variation; be brings a calligraphic precision to the laying of colour as to the statement of form, building with these a compact tapestry as in the backgrounds of certain medieval Indian painting. His dormitory mural can be said to be the culmination of this phase of his work. From here his calligraphy becomes more transparent and subtle, deceptively ingenuous and simple, almost scribble-like (as one can see in his mural in Hindi Bhavana), but seen closely it has an uncanny precision of tone and edge. After 1950 his calligraphic work becomes broader and more adventurous, permeated by a realistic structural audacity almost like some kinds of folk painting.

The last phase of his work marks the time his eyesight began to fail. Benodebabu’s eyesight was always poor by normal standards, but he had overcome this by his gift of vivid visualisation and unerring spatial sense. His poor eyesight was, therefore, more an asset to him than a disadvantage; it brought an intimate and almost visceral quality to his painting. But early in the fifties his eyesight started deteriorating further and after an operation in 1956 he lost completely the use of his eyes.

Such a calamity would have been disastrous to a lesser artist. But with Benodebabu it was different. Recluse as he had always been, he did not rue his blindness or lay off his work; he came to quick terms with the new situation. Today he continues to be as active as ever; he draws, writes, makes lithographs and etchings and, with the help of an assistant, constructs paper and textile collages. He assesses space by touch and digital measure and his vast visual memory and controlled graphic sense help to give these works great authenticity and depth. He is aware that when he works with an intermediary as in his paper cuts, there could be a margin of variation from what he indicates to what materialises, but if one recognises that throughout his whole working life he has planned things in a way that allows for such a margin of difference, one can understand his assurance and the specific individuality of these works. Besides these he has done some delightful was sculpture.

A proper study of Benodebabu’s work cannot be complete without a study of his drawings and prints. His woodcuts, etchings and lithographs are lively and individual; he was probably the only artist of his time in India, barring Nandalal Bose, who handled these graphic media with originality and distinction. His woodcuts combine an expressionist simplicity with scintillating arrangements in black and white; his etchings have a suppressed calligraphic verve. His drawings are of various kinds; some grope, some probe, some explore, some document, some plan, some improvise, some write compositional shorthand. Together they hold the mirror to an artist of great versatility.

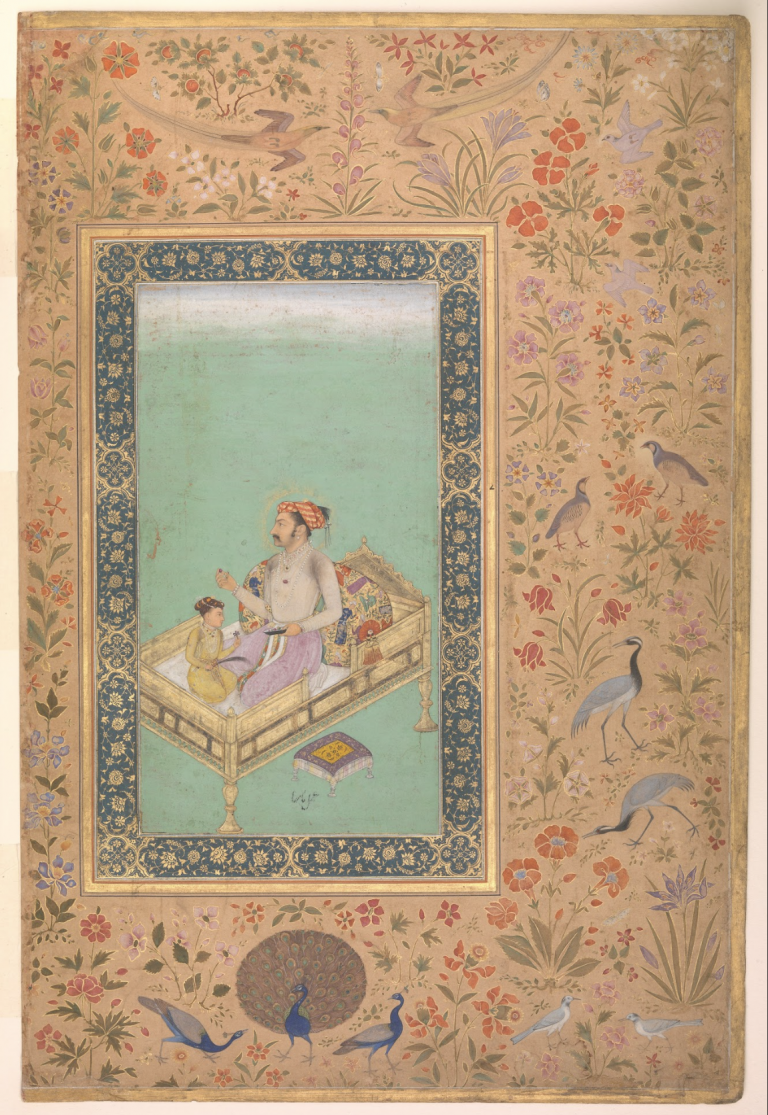

Taken together, Benodebabu’s work has great unity and variety. It is highly original but carries within it various historical undertones not surprising in an artist of his erudition and experience. If one looks for parallels one see a calligraphic quality in his early landscapes close in freshness and precision to the best of China and Japan, while in the same landscapes one can also see a tonal iridescence vaguely reminiscent of impressionist watercolours. In his murals one can see visual devices similar to those of Japanese screen and scroll painting, of Romanesque frescoes of Mughal and Persian drawing, even certain kinds of cubist landscape. In his woodcuts one can see a graphic poignancy similar to that of the German expressionists. In his later work one sees a calligraphic economy and verve rather like that of certain folk painting. But with all this, at the core his work is concentrated and original, an odyssey in the search of a composite image—whether it be in an ink sketch, a collage or a mural – an image appropriate to each dimension, abstract but palpable.