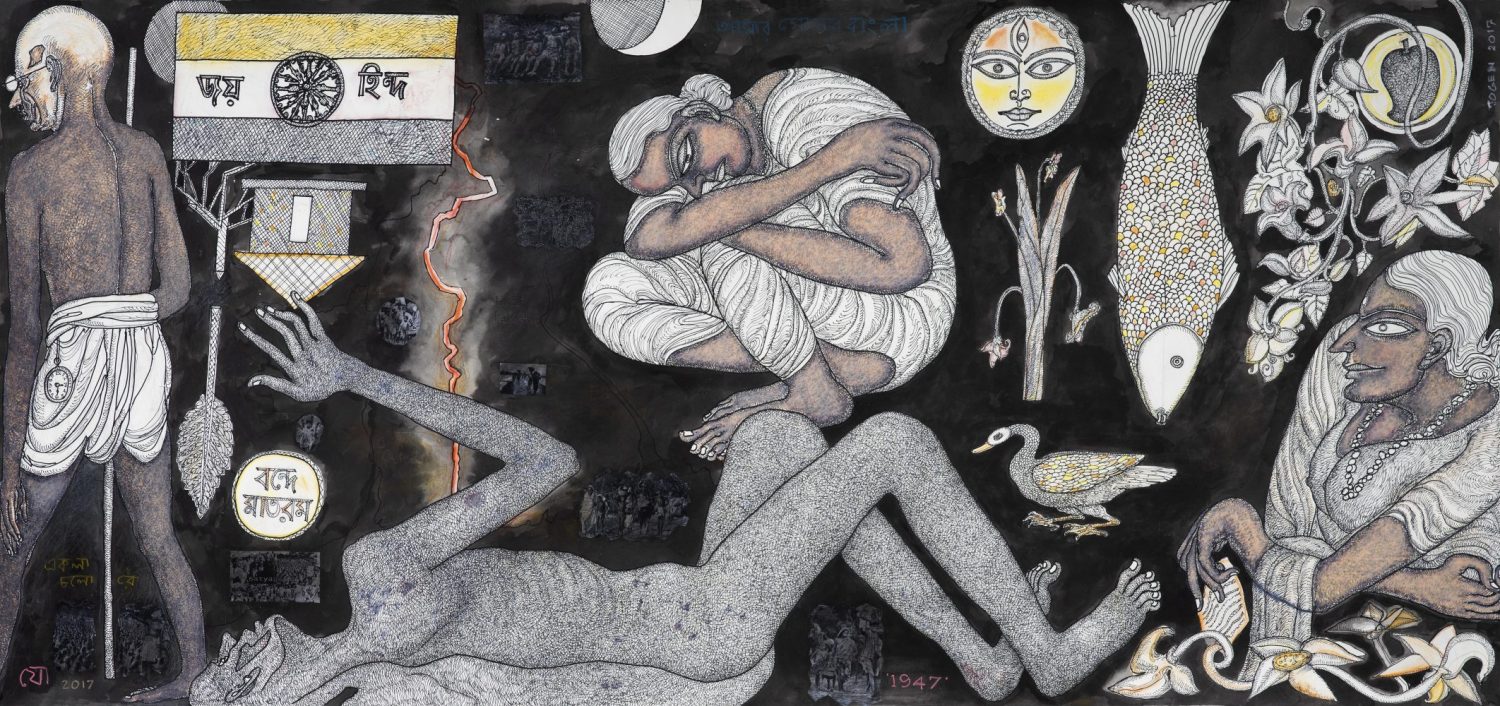

A few years back, Jogen Chowdhury completed a large work on paper called Partition 1947. Perhaps for the first time, Jogen titled a work with a straight allusion to the theme of 1947 Partition, a theme that has haunted him throughout. Yet, until this work, one cannot find a single known work by him that carries such a direct reference to this subject, right from the title. Strangely, while his other works with similar concerns are left to remain at the level of evocation and expression with indirect references to the theme, this particular painting in question leaves nothing to our evocative imagination. With the deliberate appropriation of topical and textual references, including photographic images from the historical archive Partition 1947 (painted in 2017) happens to be an exceptional work in his oeuvre. The agony and torment evoked so far through his intensely expressionist idiom insinuated with an organic inescapability, now get substantiated, as it were, by documentary evidences. Having said this, this outstanding work at the same time evades the banality of over-referentiality and turns the painting into an allegory of the Bengal Partition of 1947, replete with mediated and representational details pertaining to the pain and anguish encountered by the displaced refugees in an unprecedented scale.

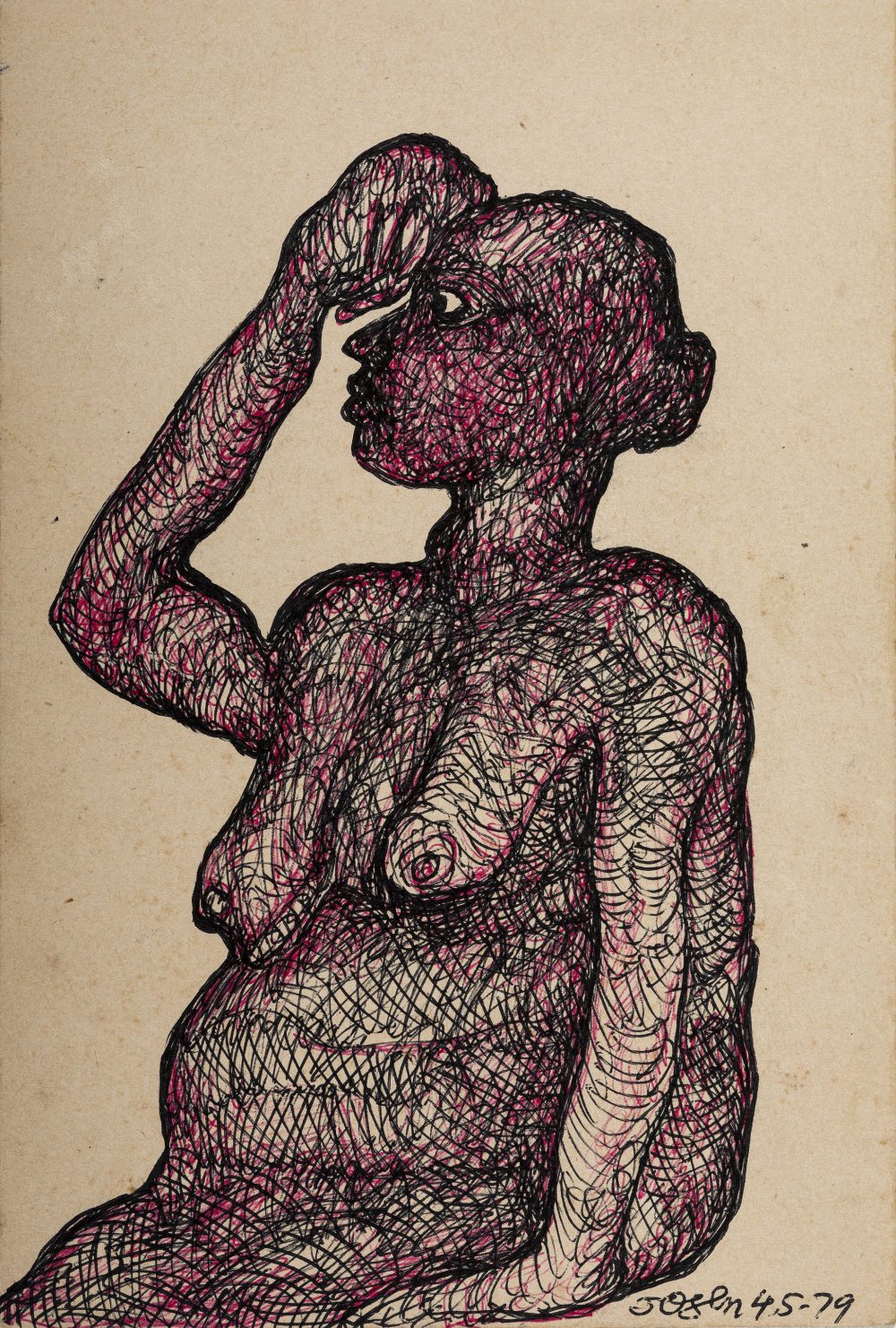

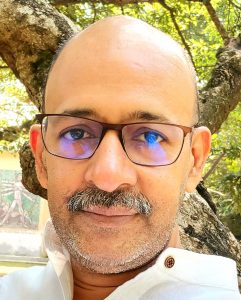

The ordeal of the Partition addressed in this painting is certainly subjective for the artist, as he and his family were deeply afflicted by it. Born in 1939, in an East Bengal village, now in Bangladesh, Jogen Chowdhury right from his childhood experienced a life troubled with the aftermath of Partition, displacement from a comfortable homeland consequently forcing them to relocate from East Bengal (present Bangladesh) to West Bengal and eventually resulting in a difficult upbringing in a Kolkata refugee settlement. The ensuing trauma and the struggle of refugee life that Jogen had experienced first-hand had a major impact on him, as is evident in many of his works, which portray listless, angst-ridden people set against a pitch-black, unspecified background. The despair is unmistakable. Yet, transgressing the personal loss and suffering, Jogen Chowdhury in this painting repositions himself as a critical and historical witness to the unfolding of historic events of 1947 India. As perceived and represented by the artist, the Bengal Partition of 1947 was a long-drawn process leading to several waves of displacements and the accompanying trauma taking deep psychological turns tainted by bloodbaths and grave misery.

The painting plays out the ordeal of the Partition in a common space, shared by prominent signs and symbols of Indian independence achieved by decolonizing the country from the grip of British rule. The artist, in a marked contradiction to the emotion of victory flagged off by the declaration of the independence, juxtaposes the reassuring textual signs reading Jai Hind and Vande Mataram with distressing images of an upturned house and a tree, a squatting woman seemingly in deep misery and the body of a naked male positioned like a fallen warrior and partially cut across by the bottom edge of the painting. As the viewer’s gaze shifts from right to left, the transition reveals itself in the most remarkable and touching way. Opulence turns into destitution, hope to despair, a sunny day to a night of waning moon, until the transition encounters the iconographic moments of independence and paradoxically a fragile border only to be finally struck by the tall image of Mahatma Gandhi on the leftmost side of the painting. Gandhi, is conspicuously seen from the back, in a posture signifying a moment of leaving the space, further suggesting a departure from the history he was so engaged with, as it were. The transition of the artist vis-à-vis his position seems to be from that of a sufferer to that of a survivor to that of a critical witness.

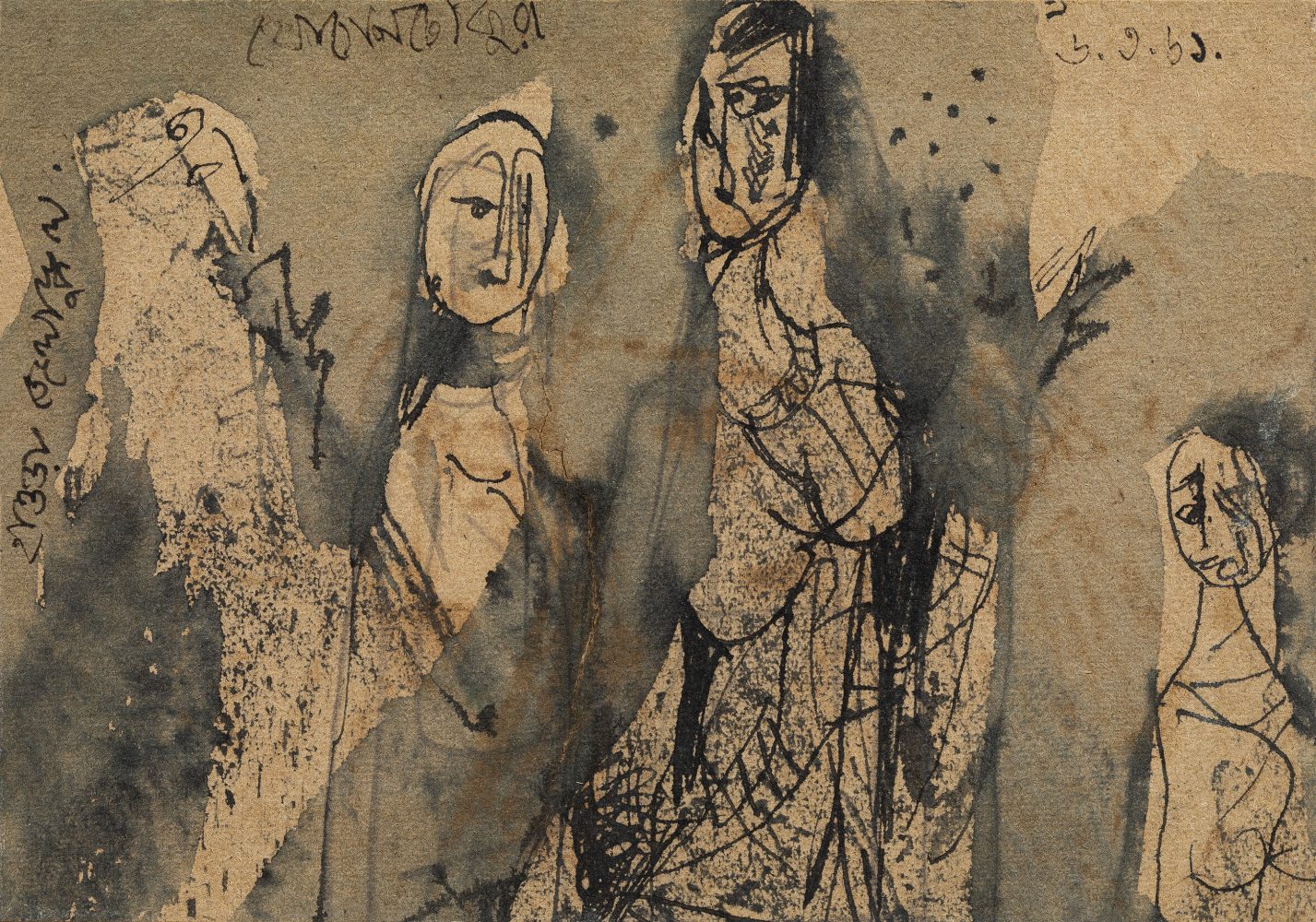

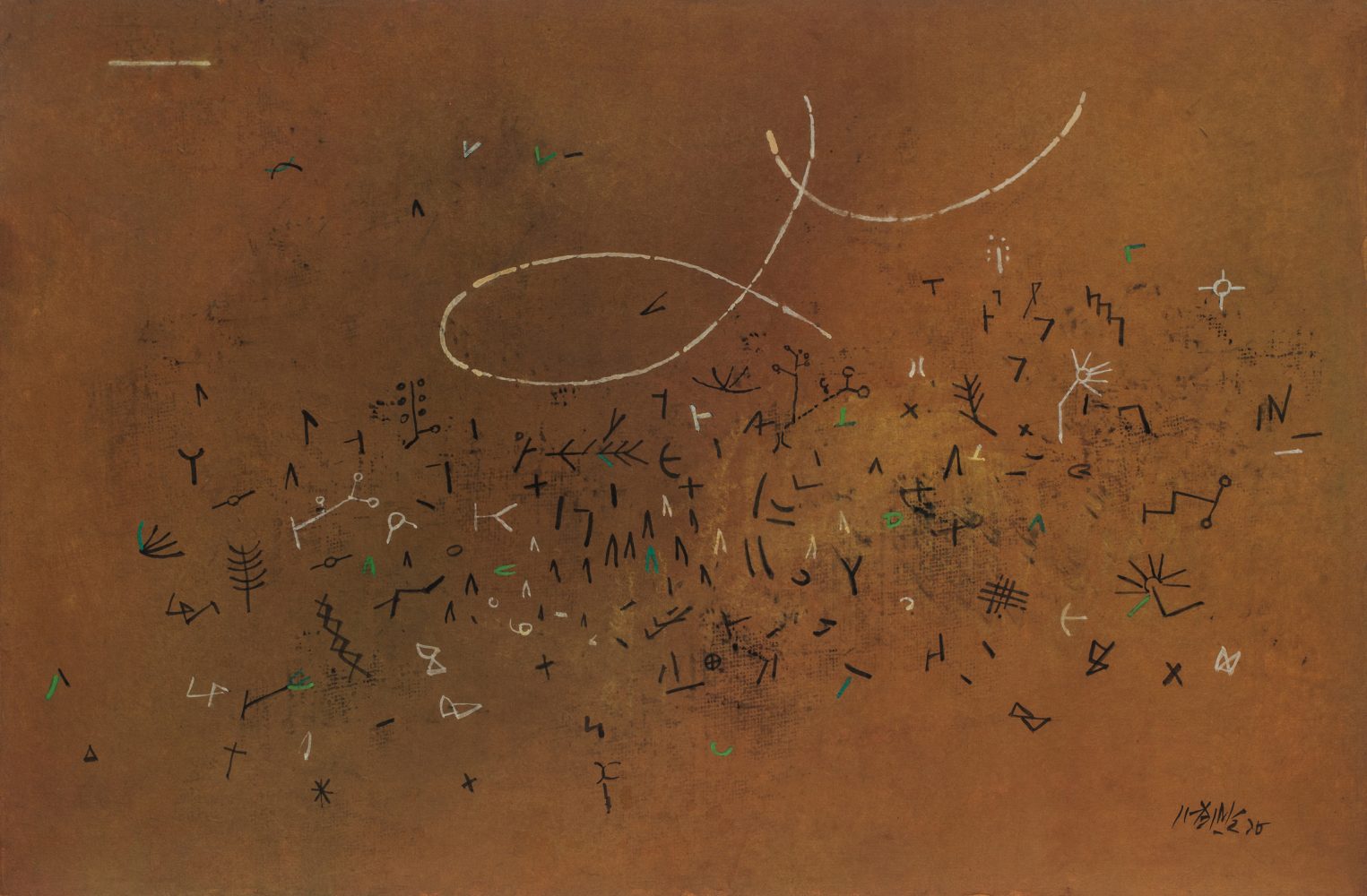

Ganesh Haloi, on the other hand, with his penchant for minimalist expressions and non-figurative forms makes his canvases and papers absorb all that is excess from the extremely distressing memory leaving the deepest marks on the surface constituting a life of their own. Born in 1936 in East Bengal, Haloi too lived the life of an immigrant, experiencing the ill-fated decades of the 1940s and carrying the memories of famine, Partition and communal holocaust. Beyond the narrative and descriptive platitude Ganesh Haloi’s art has evolved through a series of transactions from pure landscape to the innerscapes. Interestingly, the apparent obscure motifs, self-made signs and symbols and gestural strokes in his paintings and drawings are intrinsically connected to his profound sense of loss and isolation, deeply rooted in his memory.

This particular set of paintings has a specific association with the nature of water bodies. His observation of the submerged and floating aquatic plants, their gentle movements and lifecycle has been an enchanting experience that resurrects continually through glowing layers of colours and floating shapes and lines. He also induces a sense of drama, an incessant drama that seems to be an organic part of nature and independent of any human intervention. Life goes on in the aquatic lands, in vast and limitless terrains, in unfathomable spaces and the artist is a quiet participant. But when the land or the water bodies or portions of nature begin to disappear, Haloi reacts deeply with an inevitable pain. He begins to feel and even see everything despite their undeniable and starkly painful absence. In fact, absence affects him as deeply as the presence; it also kindles him to envision, to imagine the vanished space. The underlying pathos in relation to this sense of loss can be alluded to his own experience of departing and migrating in the wake of 1947 Partition, leaving behind the loved and lived land. The pain is personal as much as it is historical. Oscillating between the palpable and the intangible, between the felt and the visualised, between the memory and the present, his works strike a remarkable chord of ambiguity that sets us off to rethink the notions of memory, loss and predicament woven into the essentially non-narrative idiom of Ganesh Haloi’s works. Partition and its aftermath, migrating and resettling, loss and rebuilding are the significant and indelible memories that, for Haloi, emerge from one central idea of departure. Departure, for Haloi, not only embodies pain and loss, it evokes a sense of continuity and the ‘endlessness’ of time. During a conversation with the author (2018) Haloi says with conviction that memories haunt indeed, but they also expand the sense of time allowing the artist to map his lost terrains. The territories referred to in his art have physical associations as much as they tend to evoke the land beyond the boundaries, beyond the politically imposed limits.

Both Haloi and Chowdhury are known for their consistent engagement with their extraordinary visual language and personal style. Despite the distinctions marked by their individualism, they confront memories by embracing them, extrapolating them from the plethora of images, almost in the same pace, slow and intense. Both of them keep the visual ideas processing from the source of memories allowing them to assume newer dimensions and impressions and arrive on the pictorial surfaces through the brush and pen not as mere vestiges of nostalgia but as vivacious forms activated with refreshed energy. These astounding images may be quiet, sad, haunting, lyrical or all at once. They emerge from the past and grow into the present.

Poised at two ends of the same spectrum Ganesh Haloi and Jogen Chowdhury tend to negotiate memory in remarkably individual ways, where a sense of optimism and renewal of life glow as radiantly as the underlying passages of pain and pathos.