I can no longer hear. The whispering autumn leaves.

Everything touches me. Nothing. Touches.

I am no longer as beautiful as I used to be, he says with a twinkle that went back to the sixties and sparked memories in my head of this once and ever beautiful woman-man. Chapal Rani. The reigning queen in those days of our youth. A woman we-of-the-theatre grew up adoring. The adoration of the Chapal Rani. In the days of a purer Jatra—the travelling theatre of Bengal—when men played women. Wounding the hearts of an enthralled audience in performances that lasted an entire night. Sheer stamina. Coupled with a monumental style of acting with every gesture exaggerated to live music and declamatory dialogue. Voices that boomed and thundered and whispered and cried tears that would overflow and flood the hearts of a riveted audience of men, women, and children.

My mind goes back and forth. As I talk to this legend. Chapal Bhaduri. Now in his twilight years and no longer ‘needed’ by what I call an increasingly ‘soapy-fied’ Jatra, where female stars of the Bengali screen now play the women’s roles. Women who play women. So no place for men who played women.

‘Besides’, he repeats, smiling and on cue. The twinkling eyes mocking his own echo, ‘I am no longer as beautiful a woman as I used to be’.

We begin our conversation.

At that time, men playing women was common. There was a large market for it. Someone asked me, will you act as a woman?

I laughed … What! I’m a man! How can I play a woman!

And what about all the stuff a woman has! How will I manage!

He said, Oh, that’s okay, we’ll dress you up to look like one. To become one! If you’re willing you’ll have a job in the Eastern Railways office within fifteen days.

So I said, all right, I’ll do it.

My first role. I played Marjina. In Alibaba. And within fifteen days I got the job in the railways. But on the condition that I would agree to perform in plays for all their different departments. Dressed as a woman.

They dressed me in women’s trousers, with a bright red Irani shirt on top, a waistcoat over a brassiere stuffed with torn cloth. Knitted my hair into two plaits. I knew nothing about dressing myself then … a huge red rose right here … a pair of peacock feathers tied to my wrists, small heeled shoes and bells on my feet. They did it all. Ah, what a pretty young thing I was!

Marjina’s first entrance was with a song. The curtain had already gone up, the music had begun … I was frozen and paralysed. I’d take one step forward, one step back. At that point, this is quite a funny incident … Seeing me dressed like that, some boys mistook me for a girl. Now generally, if there’s a beautiful girl present, the boys tend to crowd around her, if they’re young. They were all gathered around me. One of them pushed me forward: arrey, bhai! Go on! Enter!

This is how it all began!

I’ve performed in so many kinds of places. People come up to me, greet me, Hey Chapal! How’re you? Chapal da! I love eating paan … I think I’ve already told you about this … Once one of my fans went off to fetch me one. In the meanwhile, someone else brought me a paan … ‘What! I go to get you a paan and you take one from someone else!’ I said, What can I do? He gave it to me. ‘Dhut! Saala!’ … Sorry … ‘Damn it!’ And he threw away the paan and stormed off in a temper. What does something like this mean? I ask you! It can happen between a girl and a boy. But between the same … how is it possible?

It was fun, I enjoyed all this.

Strange

how the air

no longer is

able to whisper

the stories

of our growing up[i]

Acting is part of our family tradition. My mother, the late Prova Devi, was a very well known actress. Theatre, cinema, radio, gramophone recordings, she did them all. Observing her, imitating, memorizing her dialogues from records, all this was part of my childhood. I would take a cloth and twist it round and round to form a bun. And I’d take a second cloth and drape it over my shoulders, and start singing. My uncles and older brothers would shout at me. What’s this nonsense! Always up to indecent stuff! We’ll give you a good hiding!

Let me tell you another story. Just beyond Chitpur is the red light district. I said, sure. I have no prejudices. I’ll go, if I need to study a character … fine. After all, I’m just going to study another person, follow her actions …

So I went. And met that lady. She said, Fine! Go ahead. After all you’re Jatra actors. I dressed exactly like her for the shows. No sindoor in the parting of her neatly tied hair. A pair of diamond earrings, a nose stud, a slender necklace … A pair of bangles, yellow blouse, black bordered sari … very much the madam of the brothel. How she uses the local toughs, or if a girl holds back money … ‘No, no. I didn’t have a client last night.’ ‘No? But I was told that you did. And that he stayed all night.’ ‘No, that’s not true.’ ‘Is that so? Jhumman!’ ‘She says there was no one in her room last night.’ ‘Just check it out, will you?’ ‘Take her to her room. Bolt it from inside.’ ‘No, no, no. Please no!’ Jhumman, the local tough, would torture the girl … Maybe whip her or beat her with a chain. ‘Go on, tell me, who was with you last night?’ ‘Here, take the money.’ ‘How much did you make?’ ‘400 rupees.’ ‘Keep 100 for yourself. Hand over 300.’

This is how I studied for my roles, and that’s what made me successful.

There was this other role I played in Natta Company …

Sonar Bharat—about Jaichand and Prithviraj. Jaichand’s queen, Purnima goes mad … How does one play a mad person? By observing one. Or else you end up babbling, laughing, crying, shrieking. I decided, No. There must be more realism in the role. In any case I tend to try and go beyond what’s on paper. I wasn’t easily satisfied. Which is why I was labelled finicky. I would say, No, Surja Babu I don’t like this. He’d say, what’s the matter? What kind of work is this? In a three-hour play, I only have an hour’s work. You want more? I said, Yes! That’s when Kaikeyi was written.

All right, Maharshi, I give you my word … my word … Until today, I was known as Kaikeyi, the loving one … But no … henceforth I shall be proclaimed a witch, a demon. O cursed night, sleep on. Dawn, do not break.

O Sun, do not rise, may you never wake. At first light, Rama will leave for the forest. All Ayodhya will be wrapped in darkness. May that black day never come.

How shall I play a mad woman? Suddenly one day, on my way to Natta Company, near the Shovabazar crossing, at Hatkhola, close to the post office, I saw a mad woman (poor thing, it was her fate, I feel bad for her) scribbling in the dust, looking up, wiping it away, scribbling again, and so on. And I thought, ah hah! That’s what I’m going to use! Yes that is what I did always. Studying real life situations. Little things that make people what they are. Soaking their mannerisms. Making them my own.

Jatra is no longer what it used to be. At that time people would joke: Jatra is watched by no-good wastrels! Why should we go see something as wild, as frivolous, as Jatra? But now, Jatra no longer has the same feel. Earlier, when I was in the Natta Company … there would be two chairs on two sides, or one chair. The concert party, or musicians, would line up on two sides. A harmonium here, a harmonium there. A huge wind instrument, the tuba, the cornet, without which no Jatra performance sounds right, clarinet, violin, table drums of different kinds, cymbals, bells … and a three cornered instrument played with a stick … which in the theatre they call a ‘triangle’ … and the one who range the bell—he really had an important role. He would hold the gong up in front of his face sideways and strike it hard! We’d feel that sound right here, in our hearts. Then the drums really got going. When the concert reached its climax, right at the top—‘Raja, raja!’ ‘Who calls? Who dares disturb me thus?’

And so the Jatra would begin …

Compared to the other men playing women, my face looked different. This was a boon, and a major reason for my popularity. Makeup—facial makeup. Earlier, Jatra makeup was done differently. You’d apply kohl with a little finger like this, or with a matchstick … make a paste of red vermilion or lac-dye … today you have powder, lipstick, eyebrow pencil. All we had was a matchstick. We didn’t have the kind of false eyelashes, made of hair, which are available now. Then we used a paste of hot wax and soot. Once our makeup was done, with a special brush, a small pointed brush, We’d heat it over a candle flame and apply the paste … This made the eyes seem bigger, and it looked beautiful. In the theatre, there are lights, under which makeup shows up well. In Jatra we used petromax lamps. Very few places had electricity. Now, of course, there is electricity in most places. With the theatre stage, first there’s the stage, then wings, footlights, Then two to four feet of space, then the seats for the audience. There’s no contact with the audience. That’s why the acting style is different. There is a distance from the audience. But in Jatra, we’re cheek by jowl with them. I have to make my way through the crowd. In other words, in Jatra we really mingle with the audience.

But the loneliness doesn’t go away. Despite all the hustle and bustle, the people, the noise, I still feel alone. It’s a part of me. Apart from my parents, the person I loved most was the friend I told you about but he, too … Love is relative, not the same for all I decided that love of god comes before the rest. And that’s what I do, isn’t it? I offer my love to god, sing Ma Sitala’s praises. So be it. I have no regrets. Earlier, I would worry: How will I survive? Earn? But now things are okay, life goes on.

I’m no longer in Jatra because the Jatra no longer has any use for me. Now I perform two or three shows a year at Sitaramdas Onkarnath Thakur’s ashram, where it is against the custom for women to perform. He has written some good plays. There, I do the direction, supervise the stage, mike, lighting arrangements the setting of the mikes, everyone’s makeup, do my own makeup and then play the main part. I really have to slog. But still, being in the midst of my work makes me happy.

And … I’ve been doing the Sitalapala, playing Sitala Ma, since 1995. Particularly when dressing as Sitala Ma, once I don the divine Third Eye, I don’t know why, there is a transformation within me. After that light talk, chatting, fooling around, is no longer possible. I’m scared. She is the goddess of disease, after all. This is my belief.

There are so many things … I sometimes wonder, are they unnatural, or are they normal? I was 18 and he was 22 … our friendship lasted for almost thirty years. A deep bond of friendship. This closeness slowly grew into a special meeting of hearts and minds, we couldn’t live without seeing each other … I really loved this, the yearning for him, the pangs of absence. We meant everything to each other. After four years, suddenly, one day he discovered something … He suggested … I hesitated, I wasn’t sure. Will this be right? But he made me agree … We had the kind of relationship a man and a woman normally have, a physical one that’s what we had … though we were both men, he was four years older, my friend …

I remember, a long time ago … I was little, then ever since I was a child this

femininity has been part of me … in my neighbourhood there was a young lad … nicely built … suddenly one day … we were talking, and he grabbed me and gave me a kiss … I really liked it … but I also felt sort of … I felt repelled … He gave off a bad smell … I felt horrible … I shrugged him off … nothing else happened, no other activities developed at the time, nor did I know about them … but something remained suppressed within me.

As for that relationship I had at eighteen … I felt amazingly complete, there was tremendous joy … in fact I got such happiness … later I read in magazines that women feel a similar physical reaction. I felt the same thing, and my friend understood this. I was like a woman in other ways too. Ever since I was eighteen, every month, at the end or the beginning of the month, for a few days I feel very weak, out of sorts, low … and after that I feel tremendously … what shall I say … agitated, and have a heightened awareness of men … and this created no problems for me because my friend was there for me, and he would make it all right …

There were problems at home, difficulties, lack of privacy and space, but a tremendous longing and desire in both of us … so we would go away together whenever I had some time off … we’d stay together for fifteen or sixteen days at a stretch … from the magazines I read it seem this happens quite a lot in the west … This thing between us, we never … we accepted it with joy, we got great fulfilment from it … in fact, we took it as art. He, my friend, would say, in fact … There’s nothing wrong with this. This is art.

Aging light

of winter

that till so recently

stretched

to my doorstep

now unable

to find its way home

in the mist

I mourn the passing of lost shadows[ii]

I gave a lot to my art. What did I get? Nothing. After moving from group to group, in 1974 I had to stop. For five years I had no work … Then Ma Sitala raised me from the darkness, made me strong, and so I’m living, somehow, if you can call this living … it’s so uncertain. A bare 25–30 shows a year. Hardly enough … But still, Mother hasn’t abandoned me, I sing her story; she hasn’t abandoned me, I have no complaints. If I can carry on, somehow, keep smiling …

What more can I say?

[i] This is a poem by Naveen Kishore.

[ii] This is a poem by Naveen Kishore.

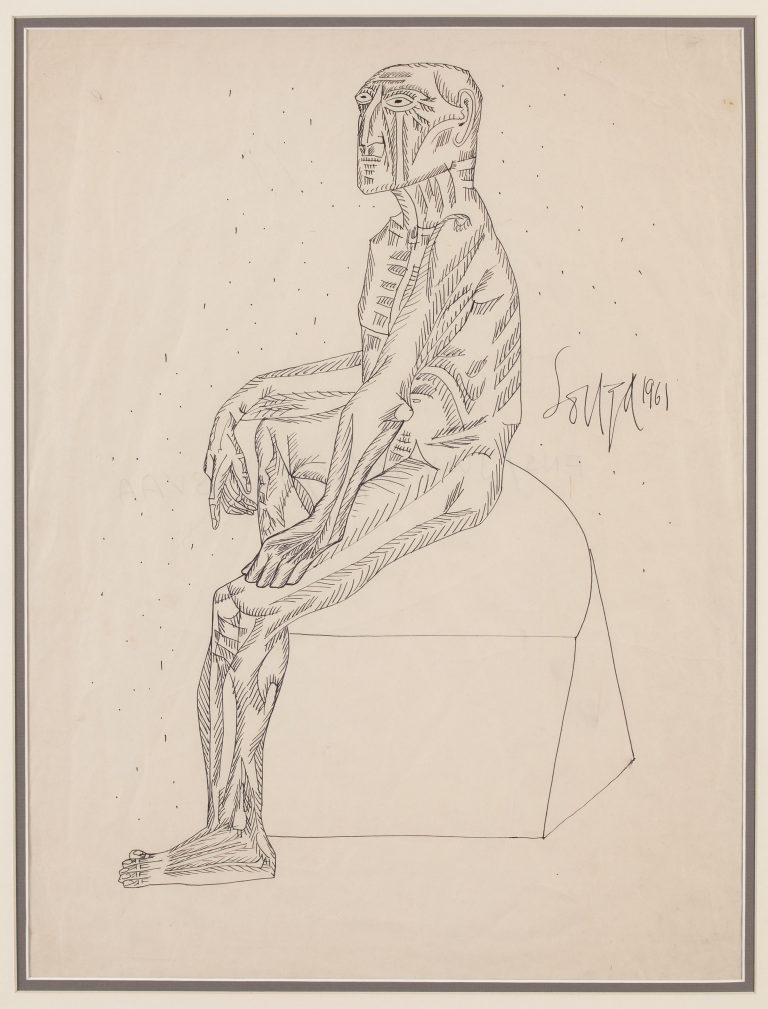

Photo credit and copyright: Naveen Kishore.