Art is a solitary pedestrian who walks alone amongst the multitude, continually assimilating various experiences, unclassifiable, and uncatalogued.

— Rabindranath Tagore

What constitutes the art of Bengal? The entire premise for this issue of TAKE Bengal hinges on that one question, and while there clearly is art from Bengal, it is the possessive preposition that raises premises and hackles. For nearly four centuries the Portuguese, Dutch, French and, finally, the British, all touched the shores of Bengal, each leaving an imprint not only on the history, politics and economics but also on the art, architecture, fashion and cuisine that have shaped this fertile east Indian riverine state.

Bengal is deeply subject to her colonial moorings and reflects the hybrid nature of her inheritance, the most enduring and ineffaceable influence is that of the British who enjoyed a monopoly over undivided Bengal for close to three centuries from the early 1700s onwards when Bengal Presidency and the metropolis of Calcutta became the seat of the British Raj in India. According to Partha Mitter, the intellectual movement known as the Bengal Renaissance represented a hybrid intellectual enterprise underpinned by a dialogic relationship between the colonial language, English and the modernised vernacular, Bengali. In this pioneering phase of Indian modernism, in Bengal the interactions between the global and local were played out in the urban space of colonial culture, hosted intelligentsia who acted as a surrogate for the nation.

Why Calcutta? During the nineteenth century with the increase in foreign trade, India became a dumping ground and port cities like Calcutta, Bombay and Madras along with Murshidabad, Patna and Banaras emerged along the shore of Ganges. Calcutta grew to be a metropolis from a small factory and strategic fort (Fort William, where my parents spent some wonderful years in the 2000s). From its humble origins in the three villages of Kalikata, Sutanati and Gobindapur, it emerged into a city of palaces and patrons, on the banks of the Hooghly, fashioned on the Thames in London. The setting up of Serampore Mission Press in 1800 became an important milestone in the linguistic development during the colonial rule. It caused the transition of the audience from the status of the listener to that of the reader. By 1850s, Calcutta was split into two distinct areas—the White Town centred around Chowringhee, and the Black Town that extended northwards along the river Hooghly comprising the Indian hub. Between the White Town and the Black Town, there emerged a Grey Town; where the quintessential Bengali babu, and the Bhadralok emerged. The School of Industrial Art was established in 1854 and later renamed as Government School of Art, Calcutta in 1864, aimed at inculcating the values of Western academism, discussed at length by Argha Kamal Ganguly in the issue. Every European artist passing through India came to Calcutta and earned a lucrative living through portraiture but remained oblivious to the indigenous art practices that existed in the region.

In early twentieth century, E.B. Havell, who was the superintendent of the school from 1896 to 1906, campaigned to redefine Indian art education and emphasise the native styles. ‘The destruction of Indian art which is going on under the British rule is a loss to civilisation and to humanity, which could and should be avoided’, he mentioned in a 1901 lecture.

A few years down the line in propounding an art department in a university in the Bengal countryside, Rabindranath Tagore prescribed an adherence to nature as one of its intents and Kala Bhavana was set up on this supposition and this is the distinctive voice and place it occupies. TAKE Bengal celebrates the momentous centenary year of Santiniketan.

The quartet — founding principal of the art school, Nandalal Bose (student of Abanindranath Tagore); it’s alumni and faculty, the stubborn genius, Ramkinkar Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee who worked through visual memory most of his life; the poet-playwright who morphed into an artist later in his life, Rabindranath Tagore — changed the way we look at Indian art forever.

Iconic works from the oeuvre of Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, Ramkinkar Baij, Benode Behari Mukherjee and Rabindranath Tagore have been illustrated in R. Siva Kumar’s essay. He, along with Samit Das, who talks about the politics of polarization, sets the tone for the issue.

This issue of TAKE on Art tries to re-explore the history and the contemporary situations in Bengal in order to regenerate an alternate form of history-writing. Situating the narrative within the framework of a number of iconic images that define art in Bengal, spanning across different historical periods, the idea is to delineate a history in parts to create a whole through a visual narrative.

We have aimed to make this a collaborative, experimental and experiential undertaking therefore we invited experts from the field to choose an artwork that is symbolic of the art of Bengal (not restricting to the present-day geographical boundaries of the region) and discovered some brilliant works selected by Premjish Achari (Abanindranath Tagore), Anshuman Dasgupta (Ramkinkar Baij), Sanjoy Kumar Mallik (Abanindranath Tagore), Madhuvanti Ghosh (Nandalal Bose), Debraj Goswami (Rabindranath Tagore), Sona Dutta (Jamini Roy), Diana Campbell Betancourt (Murtaja Baseer), Deepanjana Klein (Bikash Bhattacharya and Ganesh Pyne), Nishad Avari (Nikhil Biswas), and Indrapramit Roy (Somnath Hore). Each one has chosen an iconic work, each image accompanied by short descriptive captions that create a visual backdrop to convey the larger history. Orijit Sen and Sarnath Banerjee, have contributed humorous takes on Bengali culture through graphic strips. Columnist and author Shobhaa De through her conversation with Dilip De narrates the development of patronage through his vast collection of art from Bengal. Kunal Ray puts together the family tales of Chittrovanu Mazumdar’s family, especially about his aunt Shanu Lahiri and father Nirode Mazumdar. The issue also carries brilliant essays on Meera Mukherjee by Adip Dutta, Mrinalini Mukherjee by Emilia Terracciano, Jayashree Chakravarty by Roobina Karode, Ganesh Haloi and Paritosh Sen by Manasij Majumdar. Nandini Ghosh in her essay shares rare visuals of works by women artists from early Bengal which are hardly documented and hence, excluded from the popular narrative. In the process, we strived (and scrambled) to explore various archives to fill in the missing dots, for contributions even long past their submissions and deadlines.

With the art in Bengal having made significant contributions to India’s art history—socially, culturally, economically and politically—the tradition of knowledge production in Bengal that has its roots in the various schools of thought, continues to produce more research and dialogue around these aspects to this day. Yet, the large amount of research only reaches a limited and interested audience. History books, journals, and papers are complete with extensively researched material, but what is the community that reads it and who are the receivers?

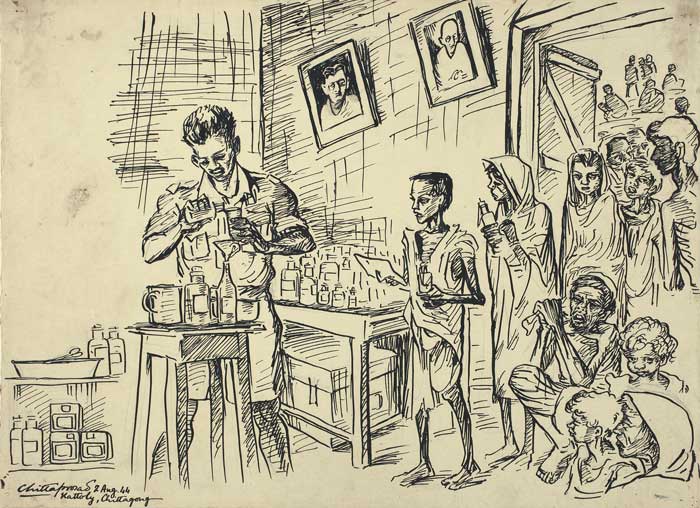

As we went through the archives, we faced the problem of selection and it became a task to form a narrative around the art in Bengal in one single issue. Some omissions that will be carried forward have been Chittoprasad, Zainul Abedin, Nemai Ghosh, K G Subramanyan; a section on Bengali artists practicing outside the region including Sakti Burman, Mithu Sen, Paresh Maity, amongst many others. In an attempt to capture the glimpses of the vast oeuvre of art and culture, and cover the artists that have been missed, we decided to bring out two consecutive volumes; the first focusing substantially on visual arts and photography (we carry a stunning photo essay by my friend Ronny Sen and the iconic Raghu Rai) while the second will include brilliant contributions on cinema, literature and more. India saw its second and very successful participation in the Venice Biennale reviewed by Annalisa Mansukhani and featured in Sitara Chowfla’s interview with art patron Tarana Sawhney. Contributions by Oindrilla Maity, Paroma Maity, Kunal Ray, Dilpreet Bhullar, amongst others add the much needed insight to our contemporary reviews section.

My sincerest gratitude to Ina Di (Ina Puri), who has been a supporter of the magazine since we launched our first issue TAKE Black, for guest editing several sections of the magazine.Special thanks to Prof R. Siva Kumar for his valuable inputs and contribution. I could not have done this without my team Rachita Gupta and Faris Kallayi, thank you so much. Special thanks to Samir Modi who has been a constant supporter and believer in our vision.

Bhavna Kakar

New Delhi