The Kalighat patachitra (painting) of the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries developed as ritual-devotional souvenirs, depicting social issues and quotidian life in the areas adjoining the temple of goddess Kali in Kolkata’s Kalighat on the bank of the Adi Ganga — the older channel of the Ganges. The genre of Kalighat painting stands at the ambivalent zone between the art forms of the decaying court and an older mercantile patronage, coalescing the folk arts of Bengal and visual practices ushered in by the East India Company. Kalighat painting, as researchers have shown (Jain 1999), was articulated along the urban contingencies of the colonial era rather than being a peripheral art practice.

Various artisanal practices and modes of craftsmanship, encapsulating new devotional moorings and quotidian experiences, are found entrenched in Kalighat painting. This genre of painting is generally considered to be holding a position between the Indian miniature style of painting and the European system of shading and tonal variations as the source of its artistic techniques. But the Kalighat painting testifies a more polemical nature of reception for its choice of themes and compositions, which had responded to the broader experience of urban theatre, cheap prints that the Europeans brought, photo studios, lithograph presses and the contemporary vernacular textual culture in print and oral performances in Kolkata. Painting techniques, tonalities and brush strokes also absorbed the materialities and sensibilities of urban craftmanship, ranging from carpentry and metal work to printing. These are again other polyvalent zones and cannot be broken down into the traditional-indigenous and the colonial-modern binary. Obscured in nationalist historiography, Kalighat patachitra was later rescued as a popular urban art practice, countering modern middle class artistic tastes to redefine the colonial Bengali public sphere. Simultaneously, the rural expressions of patachitra were relegated to the domain of the folk.

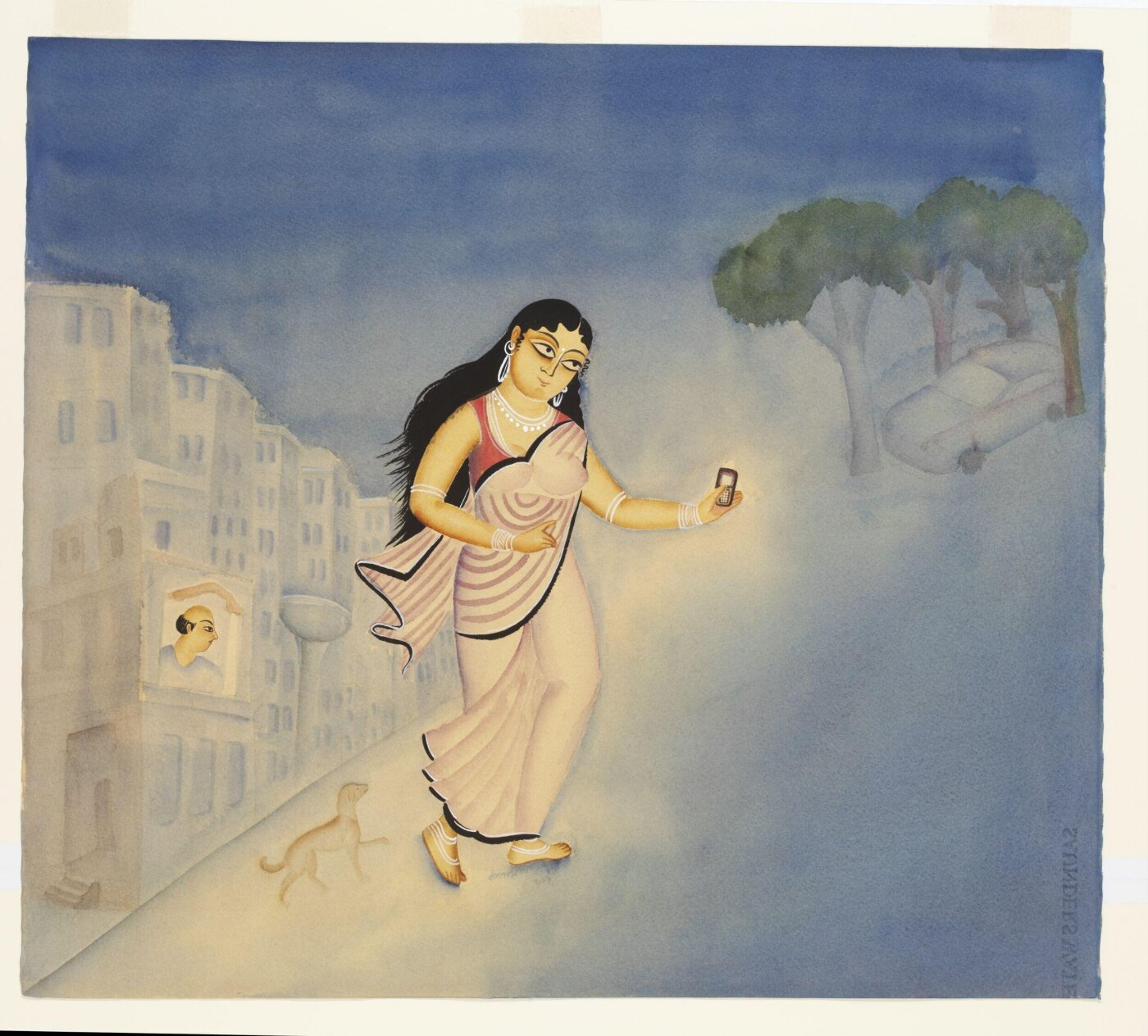

Kalam Patua, Abhisarika, watercolour on paper, 2009, Birbhum, Image Courtesy: V&A Museum.

Kalam Patua is considered to be a phenomenon to understand the response of a traditional folk visual artist (the patua or the maker of the pata) to the non-academic and popular art practices of urban Kolkata, the Kalighat patachitra. Hailing from the Murshidabad district of Bengal, Kalam Patua is said to have reinvented Kalighat painting to create his own visual narratives and stabilise his rhetoric, style and technique. Patua started as an apprentice in his family of idol-makers in Murshidabad, and learnt patachitra painting which was the hereditary practice of his extended family spread in the two districts of Murshidabad and Birbhum.

Interestingly, Patua, as a young man, had not heard of Jamini Roy (1887-1972), the painter who forged a new definition of modern Indian art by bringing together the aesthetics of the patachitras of Bengal (folk) and the Kalighat patachitras (urban popular art) to depict the quotidian life, mythological tales and Christian iconography, blending the patterns of home-sewn Bengal quilts (kantha) and Byzantine tile works. Very early into his career, Patua started showing unique compositional and stylistic innovations in his folk pata repertoire. Growing unpleasantness among the community of the patuas across the two districts he was connected with compelled Patua to break away from the ties of traditional artistic fraternity and come to Kolkata to embark on his search for new themes, styles and techniques. He visited the museums and libraries to study Kalighat painting to prepare himself. Now, Patua stands as the most vibrant figure to blend the Kalighat style and its expansive capacity to articulate pivotal moments of contemporary social life.

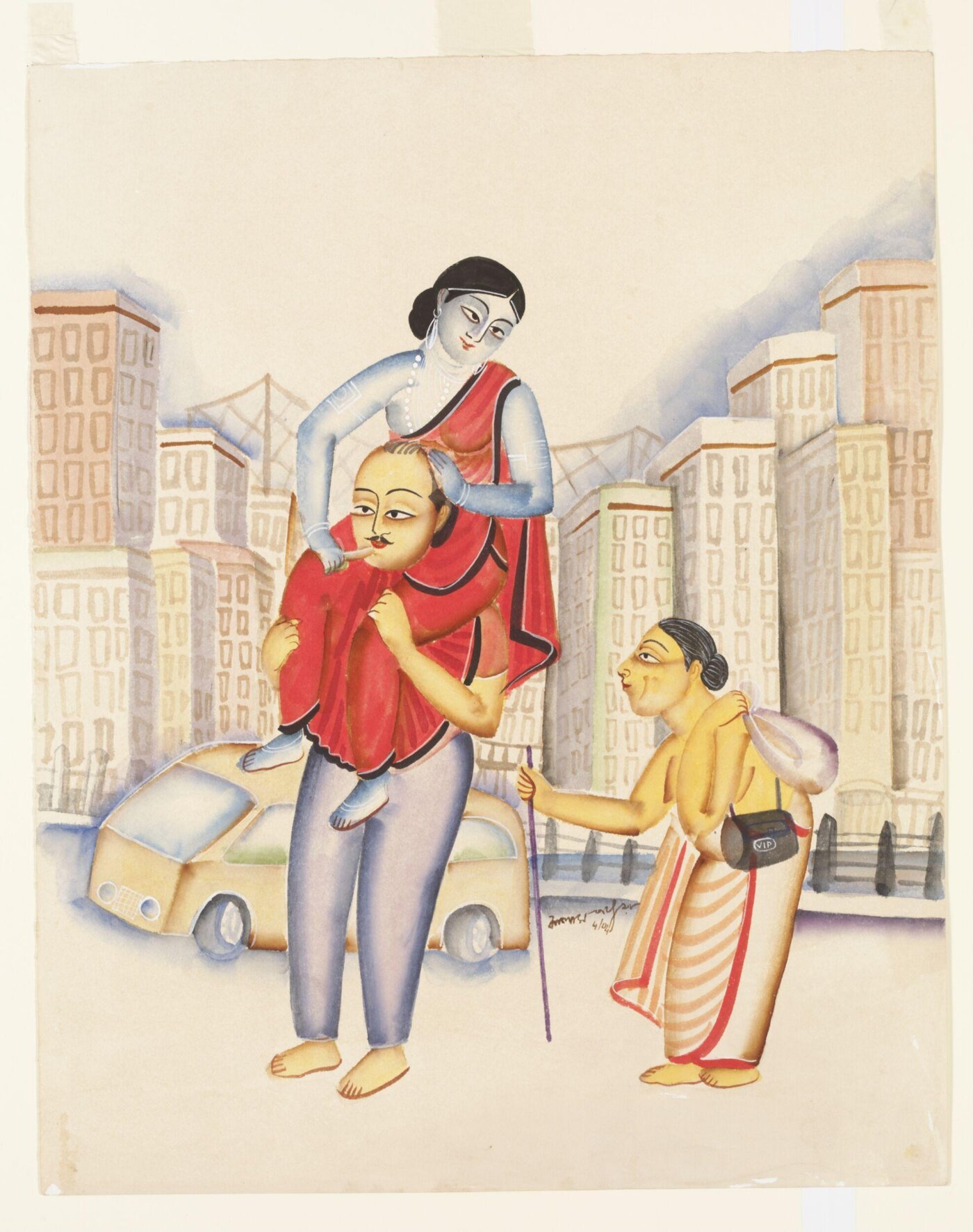

Kalam Patua, Revisiting Kaliyug, watercolour on paper, 2004, Birbhum, Image Courtesy: V&A Museum.

Kalam Patua, Revisiting Kaliyug, watercolour on paper, 2004, Birbhum, Image Courtesy: V&A Museum.

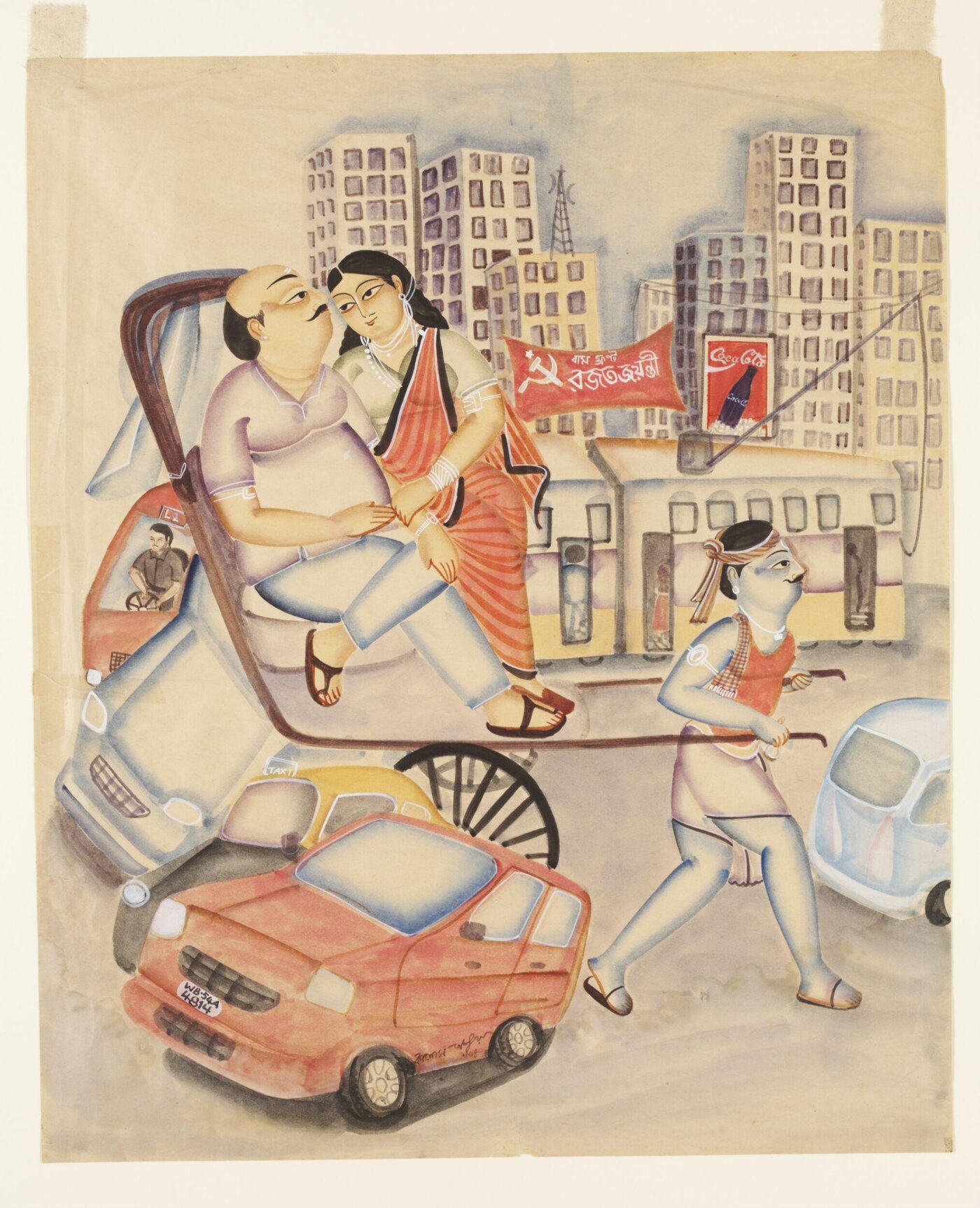

Taking the grotesque stock characters of the babus and bibis (the sensorially indulgent colonial native middle-class subjects) from Kalighat patachitra, Patua started commenting on social lives, practices, and incidents of his own times, almost like a sociologist. His compositions are plump, sometimes crowded, rich in the presence of human bodies and their movements. Not a single element in the tight composition has any less significance than the other. All the elements with multiple emotions create a central theme. His tone is mercilessly satirical towards the middle class, which he portrays as decadent and unyielding. Turning the mythological codes and idioms into outrageous transformations, Patua charges his visual narratives with critical comments on the sham middle class status quo, exchanges entrenched in sexual ploys, flirtations and dishonesty. Using soft pastel shades, toned out at the edges or borders to bring out volume and voluptuousness of the body and drapery, Patua draws black lines with free and bold brush strokes so prominent in Kalighat painting. Solid black, in hair or attire also prevails. Though his efforts look revivalist, Patua actually critically uses the received idioms, colour palette and techniques of Kalighat patachitra as an interpretive medium to tell his own stories.

Recognised across the global art fraternity, Kalam has participated in various art festivals and exhibitions in India and abroad. His artworks are collected by the individuals across the world and included in many major museums of India and abroad, such as the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, and The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the Liverpool Museum, the Museum of Sacred Art, Belgium, among others.

Kalam Patua, Oh Kolkata, watercolour on paper, Birbhum, Image Courtesy: V&A Museum.

Kalam Patua, Oh Kolkata, watercolour on paper, Birbhum, Image Courtesy: V&A Museum.

Kalam relativises the idea of the modern art, stylistically and in terms of visual art as a pedagogic practice. Being a self-taught practitioner, he stands uniquely tall outside the academic framework, redefining energetically the relationship between an artist and the institutions that create and validate generations of artists.

Reference:

- Jyotindra Jain, Kalighat Painting: Images from a Changing World (Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 1999)