How do you constitute the body through language?

Over this first week in Winterthur, I’ve tried to sort through the questions informing my project, in order to arrive at what, how and why. And to acclimatize. Right now, I have more questions than answers.

How do you constitute the body through language even as it encounters a new environment?

In this week, I have walked around a lot, been to classes, rehearsals, performances and exhibitions, and met my wonderful coaches Selina Beghetto and Julia Wehren, who are helping me network with the Swiss performance scene as I develop my project. As I walk, I wryly recall one of the first lines in my application to the Art Writers’ Award.

Walk to the left.

This runs through my head as my body haltingly reorients to a country which walks and drives on the right side. When I cross the street, should I be looking left-right-left or right-left-right? The first part of a new project is that phase where you confront your existential dread. A sense of orientation always helps.

Cat walking to the right in a city park in Winterthur. Photo by Ranjana Dave.

Cat walking to the right in a city park in Winterthur. Photo by Ranjana Dave.

This past week, I’ve made two visits to the opera house in Zurich, for different reasons. The first time, it was to attend an open class that the opera house offers to anyone wishing to discover dance. The class was mostly taught in German, with some translated explanations for a visiting consultant from Hampshire and I. I watched my hypervigilance dissolve into the familiar chronology of a dance class: a warmup, some movement prompts, some group improvisation, and then goodbyes. My second visit, with Selina, was to watch rehearsals of the ballet The Cellist, by choreographer Cathy Marston. Marston is to be the next director and chief choreographer of the Zurich Ballet. On this afternoon, a week before The Cellist opens on stage, Marston was overseeing rehearsals in two different underground studios, deep in the bowels of the opera house. In one studio, she rehearsed three different casts of lead dancers, arranged across the space based on their hierarchy within the company and the order of performance. The “script” they followed was a video recording of The Cellist, staged elsewhere, which Marston mapped to the bodies of the dancers she worked with, encouraging them to bring in personal nuances based on how they moved and acted on stage. As we exited the studio, I saw a wall covered with feature-length profiles of British cellist Jacqueline du Pre, the protagonist of the piece, and her playing. The group worked between the recording, their own bodies, and their contextual information of the role they were playing. This week, I may go watch a stage rehearsal of the piece, to see how all this information translates into performance.

On Friday, I also watched the premier of Naslah by artist Aly Khamees, who is from Cairo and now lives in Zurich. Over an hour, he shook off the norms and conventions internalized in his own body, strenuously trying to find what lay beyond those structures. The word ‘naslah’ comes from the sharpened spoons that might be used as weapons in Cairo’s prisons. I was struck by that most particular choice of title.

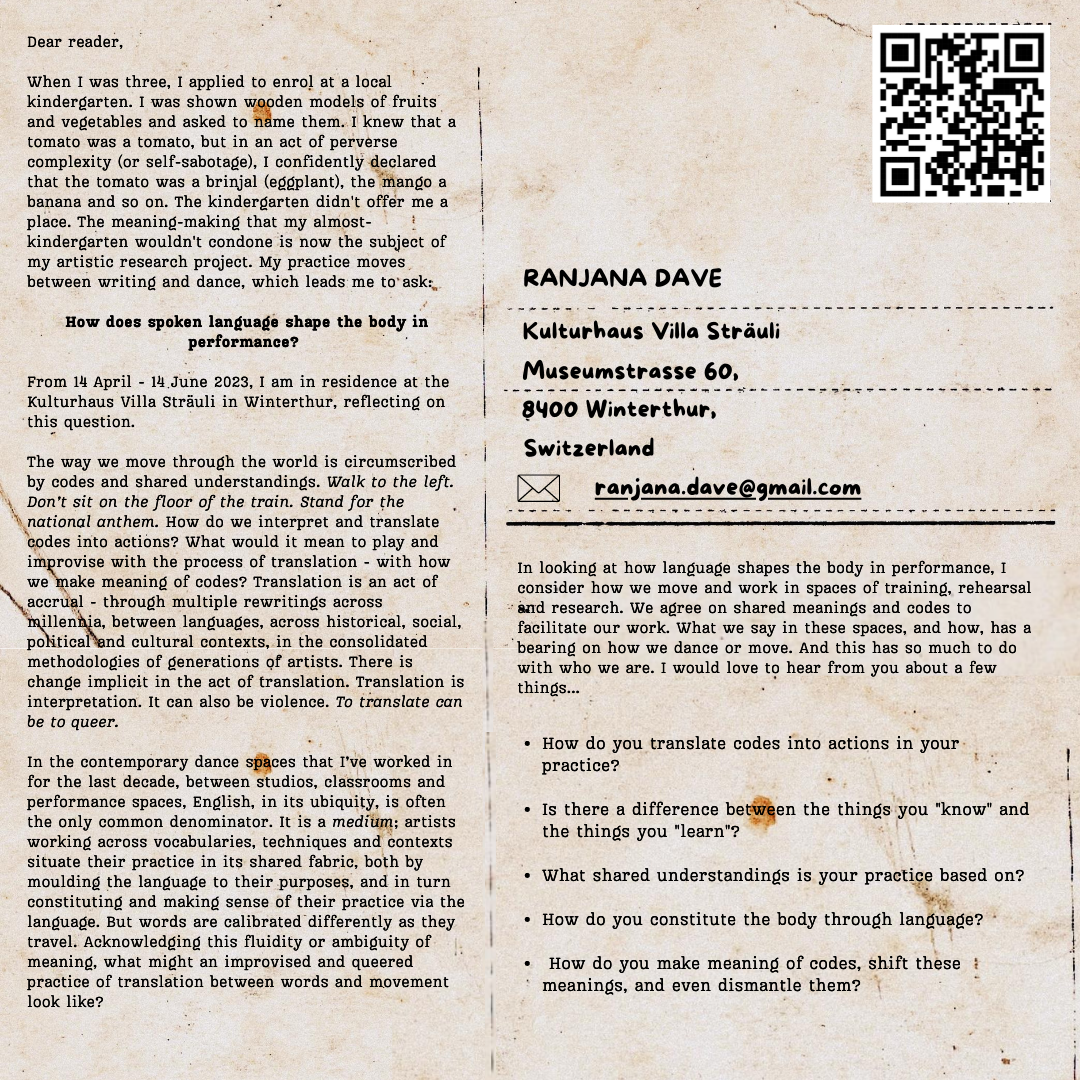

To end, this is a postcard I circulated to my residency network and others I’ve worked with earlier in the Swiss scene, as a way of encapsulating some of my research questions and initiating conversations around them.