“We don’t end at our edges” Ravikumar Kashi’s poetically titled solo at the Museum of Art and Photography in Bengaluru explored notions of porosity, ephemerality and how language could be both form and content. In this immersive exhibition, visitors were invited to engage with sculptural artworks resembling woven nets or webs of crochet and lace only to discover that they were fashioned out of paper.

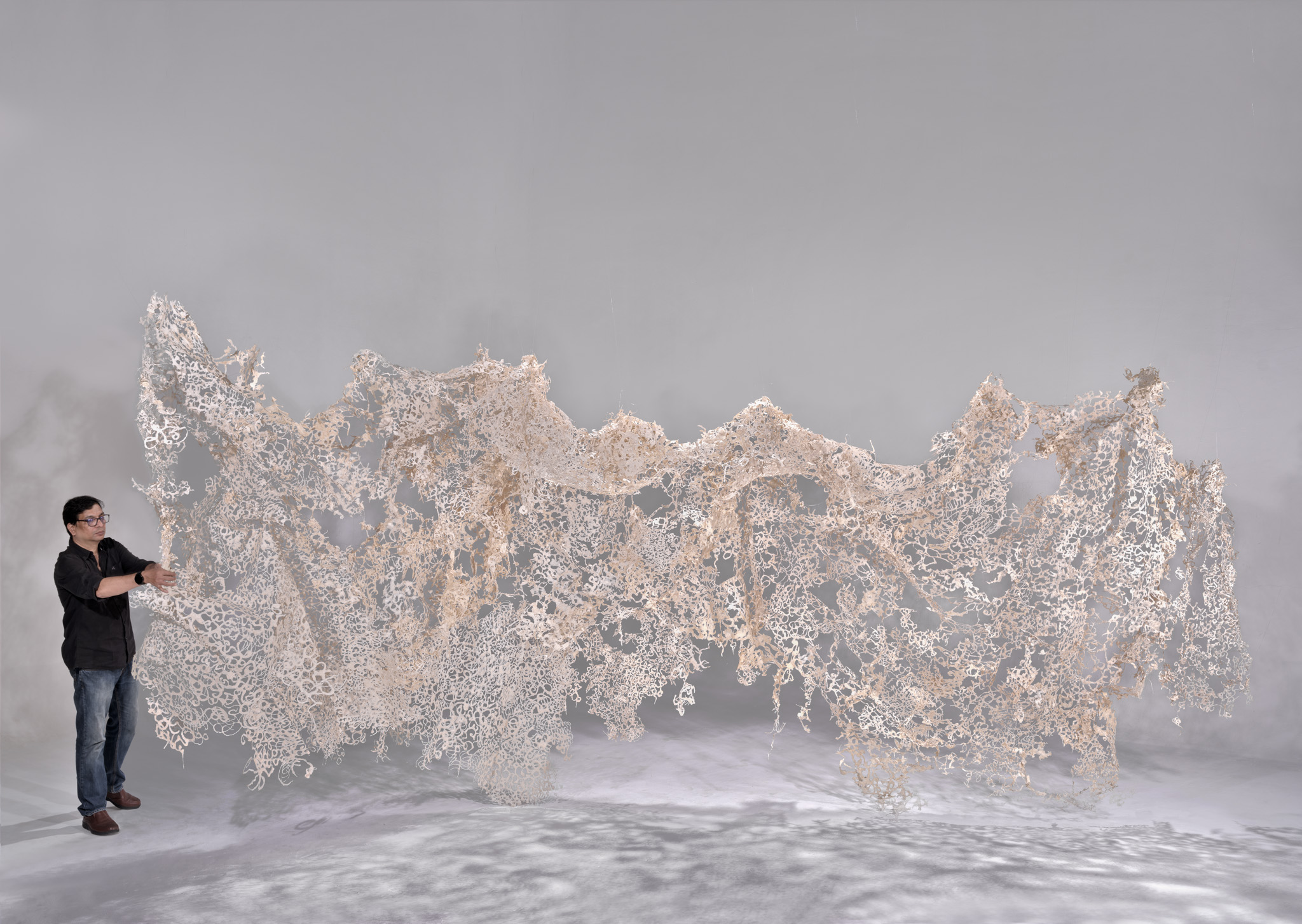

The showstopper was undoubtedly the large-scale Liminal Membrane held up incredibly in space. Visitors could revel in the play of light and shadows created by the squiggles of paper, while pondering on the material and the ephemeral, the real and the intangible. The shadow play created by the Daphne fibre pulp was reminiscent of the light that filters through foliage.

Working with paper for nearly three decades, Kashi is known to push the material to its limits, always in the search of new discoveries and possibilities in the realms of texture and tactility. A scholarship in 2001 enabled him to go to the Glasgow School of Art, which had a paper making resource centre. Under the guidance of his teacher, Jacki Parry, he was able to not just explore the materiality of the medium but also bring concepts and ideas to bear. Subsequently, on a trip to Seoul in 2008, he discovered Hanji, a paper made of mulberry bark. This sparked his interest, and he decided to take a trip to Jang Ji Bang, a family-run paper mill with a long handmade paper-making tradition. Here, he learnt both Korean and Japanese techniques. Armed with both eastern and western traditions, he has been experimenting with a variety of plant-based materials and fibres in his work.

It is this experimentation, especially with pulp painting, which has now led to the creation of the large-scale artworks that can be spied in the show. While helping a student at a workshop, Kashi discovered how he could pump pulp through a nozzle onto a plastic sheet, creating forms, which were unhindered by the constraints of a mould and deckle. Once they had dried, he could pluck them off the sheet. Talking about his practice, he elaborates, “You have a rough idea where you are going, it is almost like having a compass, not a map. You keep working and in the process of making you realize the direction and you let things develop. There is a method called making as thinking or thinking hand. You don’t think separately and make separately. Thinking and making is intertwined. That is my process”.

This very hands-on approach, without the use of assistants, is what Kashi believes separates him from several of his peers. “I am creating a counterpoint in my work to some of my contemporaries, in bringing back the visuality and the sensual nature of the material. The other counterpoint, is that when everybody is going digital, I am still working with my hands.”

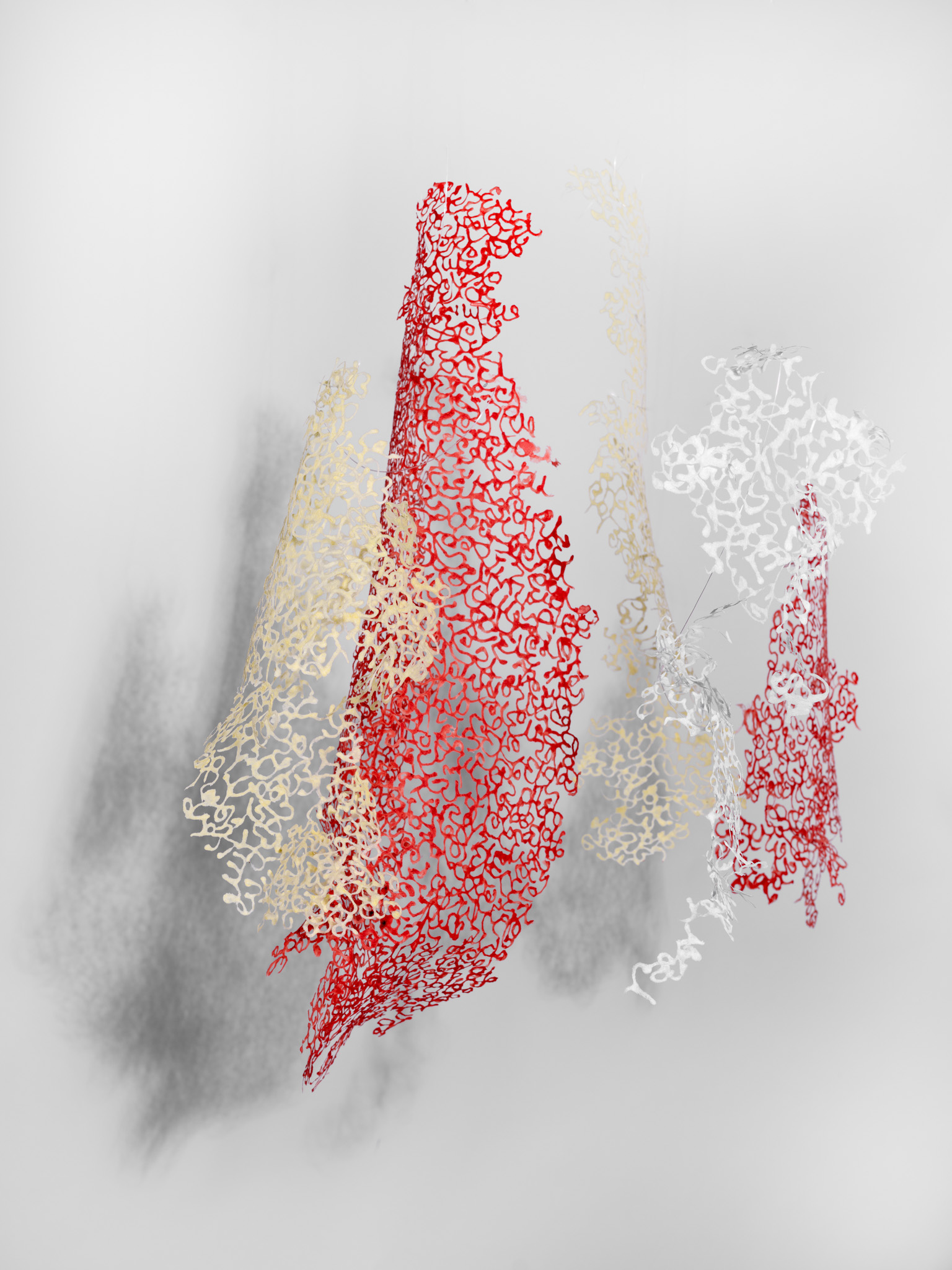

Mix of pigmented cotton rag, Hanji, Daphne fiber pulp, H48” x W24” x D16”, 2024

Kashi draws parallels between skin and paper throughout the show, pointing to the porosity and fragility of both. This wasespecially evident in the skin-coloured work number 18,created out of a mixture of pigmented cotton rag, Hanji and Daphne fibre pulp. Just as the skin is a porous membrane through which bodily secretions and even emotions are transmitted, so too paper can breathe, absorbing and releasing ait and moisture.

Cotton rag fiber pulp, H96” x W60”, 2024

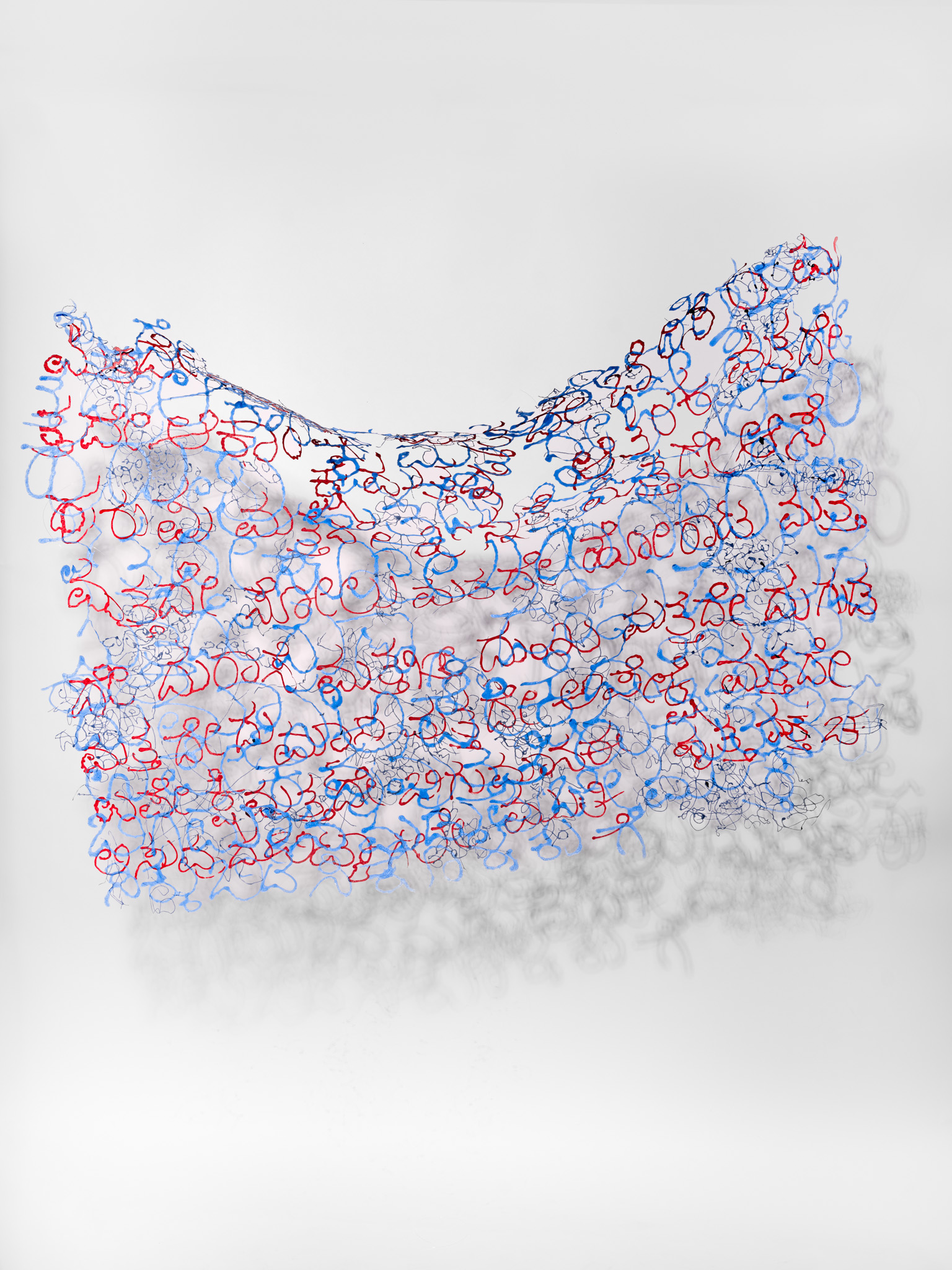

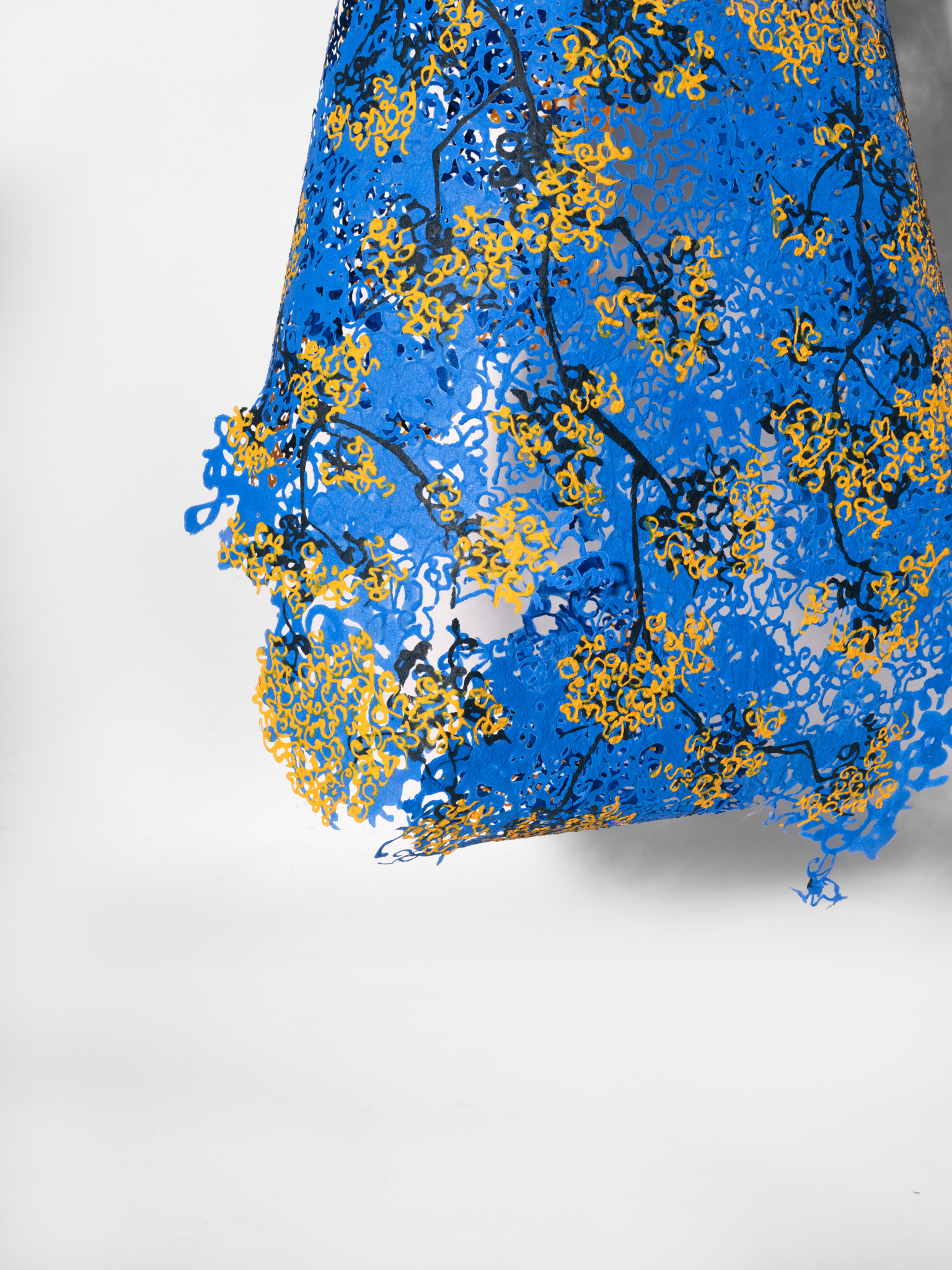

In some of the creations on display, especially works 13 and 14, Kannada alphabets could be discerned through the paper thicket. Kashi, whose mother tongue is Kannada, has been writing poetry since his student days, so incorporating texts into his artworks comes naturally to him. If earlier, paper was the passive structure on which text was inscribed, here paper itself is transformed into alphabets and text. Yet again, the concept of porosity comes into play, for language is never static but possesses the ability to absorb influences from several other cultures and mutate. Work 13, in earthy hues, was spread out on a table like a cloth but had undulations evocative of landscape. The alphabets formed a palimpsest, both revealing and obscuring meaning—a deliberate strategy by the artist to open up his artworks to multiple interpretations.

In a corner of a room, a video offered more insights into Kashi’s creation of his works. Placed below that was a book with different kinds of paper that viewers could thumb through or even feel for a tactile experience. If in the past Kashi strove to reinforce the strength of paper, now his efforts are directed at maintaining its intrinsic quality. In doing so, he does not shy away from exposing its fragility and vulnerability. Art, after all, reflects life.