The fifth edition of Kochi-Muziris Biennale In Our Veins Flow Ink and Fire, curated by Singapore-based Indian origin artist Shubigi Rao, opened in its entirety on December 23, 2022. The long-drawn-out statement has kept the art community in-waiting for close to two years now. The global pandemic COVID-19 had a medusa touch on all quarters of life. Kerala, the host state of the Biennale dedicated to international contemporary art, was one of the earliest places to register the case of coronavirus. Yet, how the Indian state Kerala, ruled by the communist party managed to keep the adversity of the coronavirus virus at bay successfully gained the attention of the media in the West. Inevitably, the closure of national borders compounded by a financial crunch, the Biennale, significantly supported by state funds, originally slated to open on 12 December 2020 was postponed to 2021. This was once more pushed to the winter of 2022. The edition of 2022, marking a decade of the Biennale, at the 11th hour was further postponed by eleven days i.e. the main venues – Aspinwall House, Pepper House and Anand Warehouse – could open to the public on 23 December 2022. Consequently, the audience, consisting of art patrons, artists, journalists, publishers, and the public, found themselves stranded on the island of Fort Kochi with most of the events pushed back. When the Biennale opened all the doors of its aforementioned sites for the public on the revised date, the online portal E-flux, dedicated to critical discourse in art, architecture, film, and theory, published an “Open Letter from the Artists of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022–23”. Until this time a variety of newspapers and dailies have reported information on the possible events – fallout between government and private real estate developer Delhi Land & Finance (DLF) resulted in delayed procurement of Aspinwall House; hard-penned customer clearance rules; paperwork demanded by the national banks to process guarantee – as the lead up to the last-minute announcement of the postponement of the opening.

The KMB statement read, “due to organizational challenges compounded by external factors, the main venues could not be opened.” The open letter by the artists hailed Biennale as a “labor of love” which was “less than ten percent ready” before the day of the scheduled opening. Besides the pragmatic and logistic challenges faced by the artist community, the letter signed by both national and international artists underscored the implication of “the ethical relation with artists and their work, including but not limited to transparency, accountability, and the duty of care”. At different junctures of the Biennale’s history, questions are raised about the monetary limitations under which the team of workers facilitates the production of a variety of exhibitions at this scale. Not surprisingly, the letter was attentive to forging a healthy environment punctuated by “respect, honesty, and care” not limited to the artists, and curators, but also the “production workers”. The courtesy access to Aspinwall House was an encounter with the dire condition that engrossed the workforce. The concoction offered at the site – floors strewn with all kinds of waste, wet paints on the walls, sparsely installed LED screens, seepage running cracks, masking sheets over the artworks – failed to conjure a promising picture, if the Biennale could meet its new deadline. To be proven wrong, in the present scenario, is rewarding. It aptly established what Rao has succinctly requested to “remember the ability of our species, our communities, to flourish artistically even in fraught and dire situations, with a refusal in the face of disillusionment to disavow our poetry, our languages, our art and music, our optimism and humour” in her curatorial note.

Here are 5 TAKE Picks from the opening week of the Biennale:

The throngs of people who came to attend the opening of the KMB’s Students’ Biennale In the Making, presented across four venues – VKL Warehouse; KNV Arcade; Trivandrum Warehouse and Armaan and Co. Building – celebrated the power of collectivism and optimism the youth mobilises. The edition is a collaborative exercise led by a team of seven curators: Afrah Shafiq, Amshu Chukki, Anga Art Collective, Arushi Vats, Premjish Achari, Suvani Suri and Saviya Lopes & Yogesh Barve. The in-situ installations by the students, nothing short of an experimental exercise, are underscored by innovation in terms of material and materiality. Nandu Krishna’s Here I was Born, made out of cow dung and animal bones brings the viewers a step closer to the experience of the notion of residues, and many manifestations of afterlives. Shubham Raj Ahirwar uses metal wire to draw a part of his paintings Memories. The shape-shifting nature of wire – leaking from the closet, fixed as a staircase support, in the shape of a chair – turns into an extension of fluid memory that the artist lives with. Sharp yet malleable, like a metal wire, is how Raj Ahirwar likes to remember a sliver of life close to himself. The pan-Indian reach of the Students’ Biennale, made visible through the participation of North-Eastern and Kashmiri students, is underscored by the exchange of conversation across the regions — the artworks deft state-fuelled isolation to speak to each other. This is epitomised by the installation Jannat-E-Kashmir: Through our eyes created by the 7th-semester students of KMEA College of Architecture in Kerala, visited Kashmir to recreate its beauty in the form of the ceiling-to-floor installation at Arman and Co. Building.

One of the main highlights of the opening week was William Kentridge’s lecture-performance Ursonate at the Cochin Club. Having showcased More Sweetly Play the Dance, an immersive, multimedia experience on emigration, exile and mortality, in the last edition of KMB, this time Kentridge did a live performance Ursonate. Based on a Dadaist poem written by German Kurt Schwitters in 1932, Kentridge puts the written and spoken word into a string of togetherness along with animated video and improvised music. Labelled “degenerate” by the Nazis, Schwitters dismantles norms of structures to expound on the idea of conversations. In a similar vein, the dynamic sequence of the performance, which unfolded for the first time in front of the audience at the Cochin Club, held a promise of engagement. The illustrative oeuvre of Kentridge builds on the hand-drawn animated drawings and films to critique the difficult histories of the colonised. The sound poetry undermines the supremacy enjoyed by the written word of colonial politics to anchor a discursive world peppered by eloquent lyricism not stringent to the edifice of words.

The title Our Veins Flow Ink and Fire foregrounds the power of the human community to be a carrier of change. In other words, the artistic practice dovetailed with the political commitment to nurturing the play of finesse and flame of a revolution is encapsulated by the exhibition How to Reappear: Through the Quivering Leaves of Independent Publishing III presented by Kayfa ta (Ala Younis and Maha Mammoun) at TKM Warehouse. The Arabic term Kayfa ta translates to how (‘kayfa’)-to (‘ta’) manuals in English. The alternate publishing platforms showcased here talk about the politics of representation: the unsaid lines of demarcation between the field of creativity and professionalism. At the centre of the hall, the printer suspended from the roof allows the audience to watch reams of paper incessantly soaking a splash of blue ink. The independent publications, be they literary or visual, through the annals of history,document the subaltern side of the nationalist agenda. One such example is the “Trolley Times”, published by the artist-duo Thukral and Tagra. The initiative conceived during the times of farmers’ protest spread across the borders of the national capital New Delhi and Uttar Pradesh (steadily moved to the rest of North India) archived the everyday struggles faced by the agrarian community. Towards this end, the newsletter opened an arena of collective possibilities – evidential, journalistic and lyrical – to realign the capitalistic-motivated changes in agricultural laws.

The idea to conceptualise the national history of dominance was (re) manifested through the large-scale exhibition Geographies of imagination: My Language is a Bedouin Thief at Dutch Warehouse featuring Hera Büyüktaşcıyan, Gladys Kalichini, Fazal Rizvi, Samra Mansoor and Yara Mekawei. Dutch Warehouse as the name suggests is home to interconnected histories – breathing and living in flesh and blood at the Malabar Coast. Following the previous iterations in Berlin and Dhaka, the third exhibition remaps the histories of linear borders carved across Karachi, Kochi, Hamburg, Chemnitz, Nuremburg, Munich, Lahore, Leipzig and Cairo with multi-media installations such as sound, audio-visual, text-based works. The video installation The Fleet by Fazal Rizvi at the display was made during the height of the refugee crisis in 2016. Fluid oceanic waters and rickety wooden boats as the two leitmotifs of the video when encountered in the dim-lit room of the Dutch Warehouse reimagine the living experience as played out at the multiple shores of every continent. Homed inside the Warehouse, where the revving engines of the ferries and ships alike are a present-day reality, The Fleet becomes a metaphor for the continuation of a non-linear time: a hard-earned fact deemed to be ignored.

In the absence of the main exhibitions at the venue, the Satellite shows gained momentum during the first week of the Biennale. The exhibition Anatomy of a Vegetable – Ruminations on Fragile Ecosystem by Prasanta Sahu in Mocha Art Cafe in the Jew Town of Kochi is an intimate interaction between an agrarian way of life and contemporary built-structures. A step forward from the break in the tactile experience of the artworks due to the pandemic, Sahu experiments with materials in an effort to yield the fecund sites of engagement between urban and traditional ways of life. The interactive project draws from the workings of a landless farmer named Lakhmi Rans Khanda who engages with the traditional practice of farming. A series of conscientiously displayed plaster casts of vegetables and drawings of plants as well as the digital details of the cartographic fields reimagine the abundance of nature within the framework of classification and documentation. The project is a subtle indictment of human obsession with the act of occupying fields of plants. By way of explanation, as the human tribe overlooks the patterns of life breathing within the folds of greens, Sahu tactically subverts the features of urban life – digital technology and modern construction material – to undermine tools of dominance.

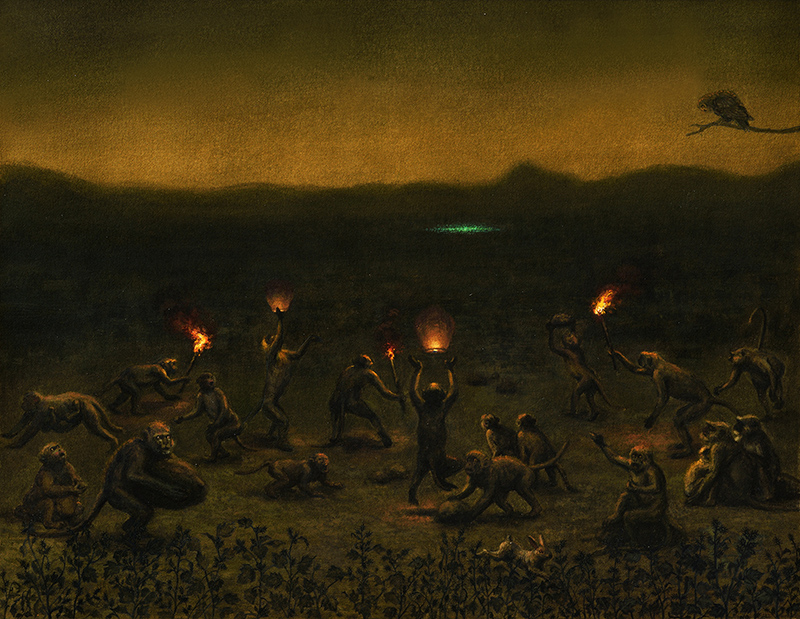

A good fella, who managed to extend the stay in Fort Kochi till all the venues opened its door for the viewers, confided over a telephonic conversation that these exhibitions are steeped in politics. The tone of a pleasant surprise of having such a rendezvous was unmissed, yet it did not fail to suggest that the feasibility of this statement was a sharp corollary of the environment pinned by claustrophobia instead of being conducive to art and cultural practices. It is reassuring to know that since the first edition of the Biennale, co-curated by Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu, it has sustained the argument that “good art is good politics”. To defy the act to mirror lived reality sans question is to probe the citizens to rise to the occasion of concern. Here, a reminder to an etching When Rabbit Saw the Falling Sky by India’s leading printmaker Ketaki Sarpotdar at the Aspinwall House is appropriate. The community of anthropomorphic animals stands in an open field with fire batons pointed towards the vast expanse of sky. The strident busyness of the scene hints at the urgent action demanded of the current situation – it is the shimmery glow of light, engulfed by an otherwise midnight blue sky that lends a glow to the faces. The artistic imagination shapes the analogy between humans and fauna, framed within the modest size of the etching, to speak what the Biennale hold at its core: the flame of knowledge, or as the ink which flows through our veins, resides within our collective selves to enlighten the world that we inhabit.

Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022-23, is on view till April 10, 2023, in Kerala, India.