Gratitude, wonder, and elation were evoked in the title of Anjum Singh’s much-anticipated solo show ‘I am still here’ at Delhi’s Talwar Gallery. The exhibition was rendered all the more poignant because Singh, who had been battling cancer for several years, had a near brush with death in the summer of 2019. It was therefore scarcely surprising that beneath the veneer of a triumphant and joyful comeback, undertones of physical trauma could be discerned. Here was clearly a vivacious spirit, trapped in a failing body. Then barely a year after that moving exhibition, she had succumbed to her illness.

Although Singh did have a show, ‘Masquerade’, at Talwar’s New York gallery in 2015 shortly after she was diagnosed with the disease, this was her first solo in India in almost a decade. It must be said that the artist never consciously wanted to make her ill health the subject of her work—it transpired organically. The onset of her illness in 2014 necessitated countless trips to hospitals, both in India and the US, as she sought a cure for a disease that had insidiously infiltrated her body. These experiences took form on paper and canvas, not in a manner that was morbid but one that exuded a fragile beauty, holding up the frailties of the flesh to scrutiny.

This was especially evident in her watercolours on paper, where in the three-part Bleed Bled Blood Red, the smudges of colour mimicked bodily secretions. In the most delicate of the trio, a burst of black and blood-red was surrounded by a halo of fine striations, endowing it with a flower-like quality. In contrast, the other two works conjured up memories of blood tests to gauge the progress of a disease, each smudge indicative of the body’s health. In one, the numbers below the stains appeared to mark the march of days, while in another they were boxed in to form an irregular grid with some of the squares bearing words like ‘alkaline’, ‘mineral’, and even ‘Singh’. The insertion of the artist’s name completed the objectification of the artist’s body, reducing it to a subject of cold and clinical examination. Nearby, pain was distilled into reddish smears on a sheet, which bore the sentence ‘Samples February 2016.’

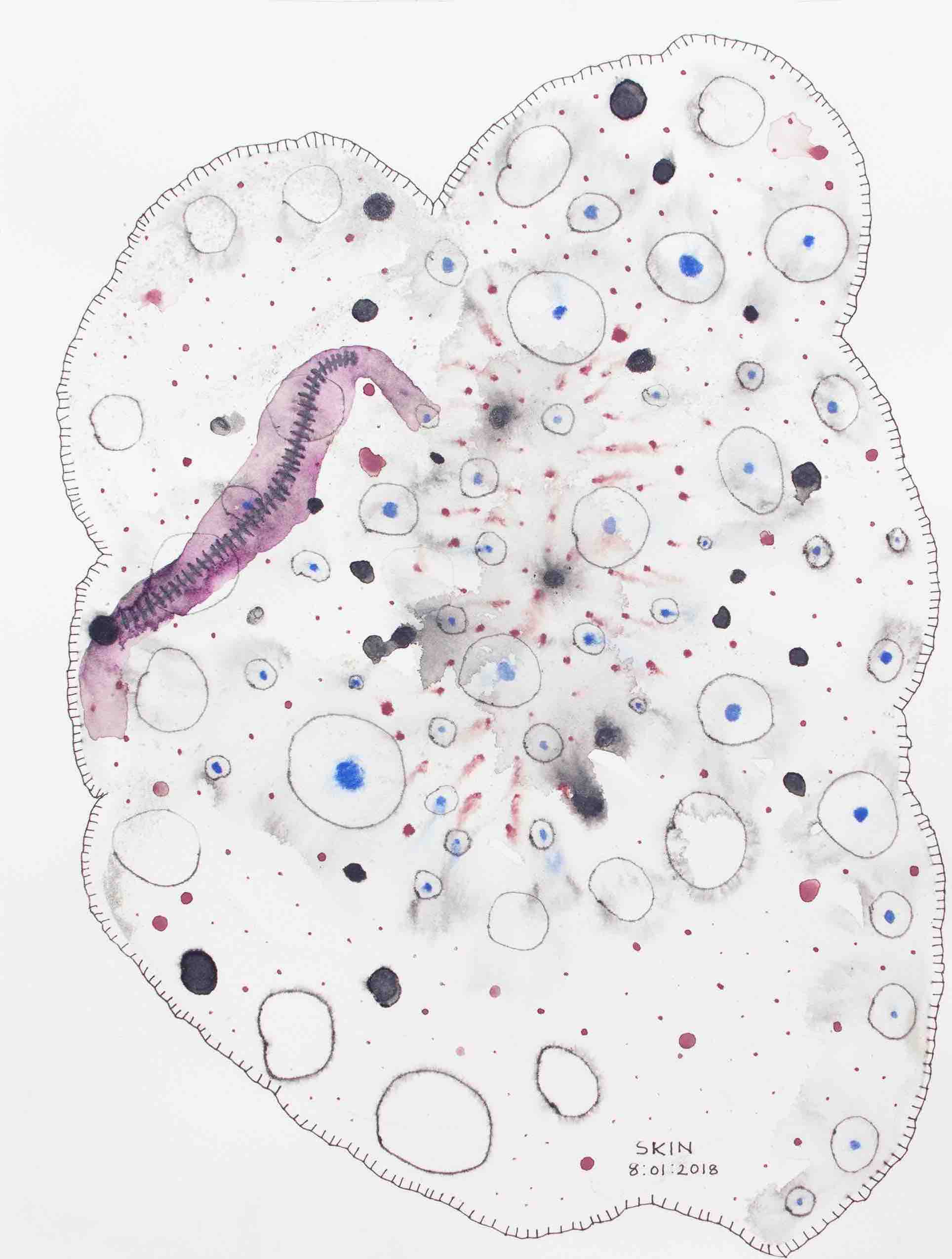

It was perhaps telling that in the exhibition the artist presented parts of the human body, never its whole. Hers was an investigation into the body’s interiority, into flesh and bone. In the suite of 24 watercolours, graphite, and dry pastels titled Remarkable Unremarkable, a scan of a skull made an appearance, while in another work a heart-like form occupied centre stage. Singh’s sense of sheer incredulity at the fact that surgeons continued to stitch up the body, despite advances in medical science, manifested itself in another work in the series. Using artistic licence, she replaced the sutures with the more efficient zip in a work that bore the word ‘skin’ at the bottom. Elsewhere, in Cobweb in My Head, a delicate dendron-like structure was reminiscent of the spinal cord while in My Body: Candy Floss, the black masses recalled organs, tumours, and other bodily appendages. However, Singh, who all through her trials and tribulations never lost her tongue-in-cheek sense of humour, poked fun at her internal bodily mechanisms and got the dark and dense forms to sprout pom poms of fuchsia and warm red.

This pop sensibility is not new and has always informed the artist’s oeuvre, manifested in her choice of palette. While brooding blocks of graphite black seemed to be a more recent inclusion in her work, gravitating to reds and pinks came naturally to her. Two decades ago, in a conversation with her artist friend, Manisha Parekh she had opined, ‘I am very comfortable using red and I know that if something is not working, I can use red to make it work.’ She has certainly moved on since then, imbuing colour with an intentionality and significance. Red now signified not just celebration and passion but also blood and tears.

In contrast to her delicate watercolours, with their expanses of negative spaces, her large canvases in the show exhibited a medley of textures. Singh produced richly pattered surfaces by employing corrugated materials and bubble wrap. In a ritual of repetition, which the artist found almost meditative, she used stencils to create circular shapes on the surface of her canvases. But equally, a new-found desire for letting go, for abandoning herself to delicious accident, as evident in the spreading stains in her watercolours, made its way into the canvas works as well. As Singh realized through the course of her illness, not everything could be pre-determined or predicted. Her innate love for structure was now juxtaposed with a certain fluidity. In Belly Button, near a realistic large button, a delicate mesh-like structure covered an amorphous spreading mass, as if to stop it in its tracks. In Heart (Machine), the form of a mechanical part of a bike—strangely reminiscent of the body’s pumping mechanism—set up a striking contrast to the undulating red and pink net-like background. Singh adroitly used shades of colour to impart a tremendous sense of movement to the work, giving it in the bargain an almost op art feel.

Nearby, a suite of watercolours traced her experiences during her sojourn for treatment in the United States. Alluding to the wild fires in California in one paper work, in another she made references to the structured gridlock of New York’s streets, disrupting it with blotches of colour. Revelling in the use of water-soluble pencils, the artist used them to create sharp lines which mimicked the needles that punctured her veins, exploiting them as well for their ability to create gently spreading clouds of colour.

Her references to the city and her fascination for mechanical parts was also a continuation of her earlier practice. In her show ‘All That Glitters is Litter’ mounted at Delhi’s Vadehra Art Gallery almost a decade ago, she had turned the spotlight on Delhi’s urbanization, the lack of basic civic amenities and its detrimental impact on the lives and health of its inhabitants. She had made visual connections between the city and the innards of the body, with pipes recalling the body’s internal plumbing mechanisms. An intestine-like pipe made an appearance in the oil on canvas Alien, the title suggesting body cells gone rouge. Here too her penchant for using the inorganic to mimic the organic and the artificial to reflect the natural come to the fore. If Singh’s show can be read as her ruminations on mortality, then the afflictions of the flesh have never looked more poetic.

‘I am still here’, Solo show by Anjum Singh, Talwar Gallery, Delhi, September 9, 2019–January 4, 2020.