The COVID-19 pandemic led to the cancellation of several exhibitions since March 2020 in the face of a nationwide lockdown resulting in almost all artistic activities, including exhibitions since then going online. The last year and a half have been a desperate attempt to recreate everything that physical spaces and interactions provide in online spaces, often without reflecting on how we engage differently in the two realms. Although the successes of these shows were hit-or-miss, the forceful migration to occupy digital spaces was one born out of absolute necessity. However, one of the exceptions that fit well within digital curatorial contexts is ‘VAICA 2: Fields of Vision’, curated by Bharati Kapadia, Chandita Mukherjee, and Anuj Daga. The attempt is not to digitally mimic the experience of a physical gallery space, but to use digital tools and strategies for curation and exhibition, all the while being cognizant of the viewer’s experience. Though the curatorial note acknowledges the pandemic as a site contextualizing the screen as ‘new geographies of inhabitation’, the exhibition has a potential beyond being defined by the pandemic in its curatorial methodology in the virtual space.

‘VAICA 2: Fields of Vision’ presented 121 videos by 79 artists, divided over four weeks. Supported by Vimeo, a selection of videos was available online each week with a curatorial theme and a following panel discussion. As most of these works are not available online for free viewing and are often showcased in the context of an art exhibition, ‘VAICA 2’ birthed an opportunity to make the works freely available even if only for a limited time. The curatorial themes were: ‘Cartographies of Sensation’, ‘Orbits of Desire’, ‘Peripheries of the Real’, and ‘Urban Heterotopias’. The exhibition was hosted by Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum in association with the Comet Media Foundation on the VAICA website.

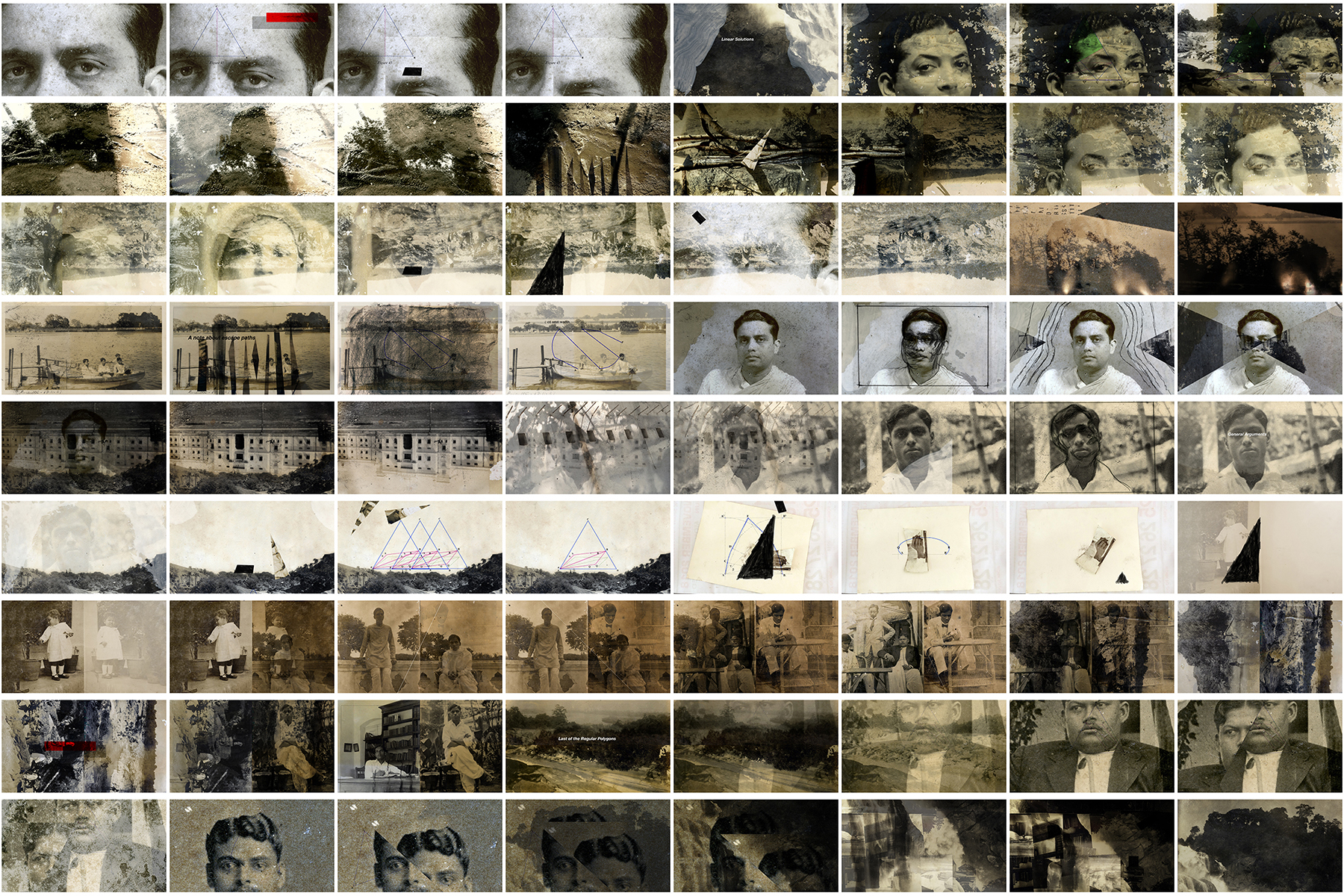

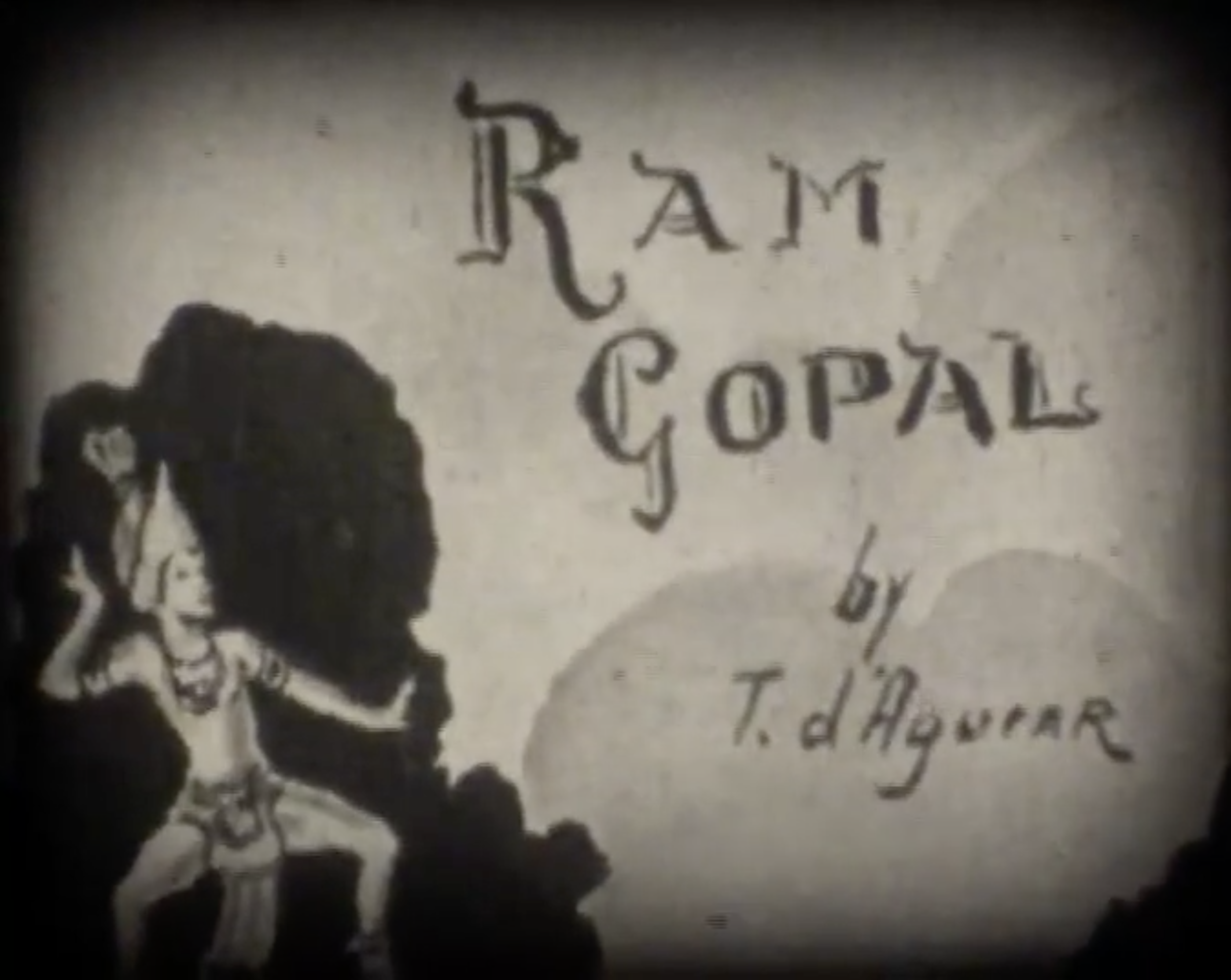

Of this extensive list of artists and some truly remarkable video works, I was drawn most to Ayisha Abraham’s four films, Amnesia, I Saw a God Dance, Straight 8, and You Are Here, under the curatorial framework of ‘Orbits of Desire’. These films are a play between memory and fiction in their ephemeral state. Though, much has been written about Ayisha’s films, what is most striking is the engagement with technology of the people who appear in these films, its connection to the current socio-cultural context, Ayisha’s relentless approach to filmmaking, and finally, the inevitable materiality of the surface of the film reel deteriorated over time and circumstances. The Dancer Ram Gopal, wanting to be recorded in colour, approaches Tom D’Aguiar, the protagonist of the film Straight 8, a third-generation Anglo-Indian photographer residing in Bangalore. Ram Gopal’s fascination with colour film and his desire to be recorded led Ayisha to discover him and work on the multiple iterations of I Saw a God Dance. Towards the end of Straight 8, D’Aguiar, now in his old age, says, ‘I have been very lucky to have seen all these advances in technology which have given so much enjoyment to us.’ When I interviewed Ayisha in December 2021, she had said that she had retreated from film making into a practice that is more current. For her, digital technologies feel far more ephemeral than analogue technologies due to changing formats, difficulties in maintaining integrity while translating from one format into another, and ultimately, crashing of hard drives. Contrasting these anxieties of digital film mediums is the 8mm film that she found of Ram Gopal dancing on his sunny terrace, in a dire condition in a plastic bag that held in its fragile memory the afternoon when Tom D’Aguiar filmed him.

Sukanya Ghosh’s Isolation of Pectoralis Major starts off with still images from a body building manual and transitions into visuals of medical screens that monitor different individual aspects of the body. The fact that the body needs to be seen from the perspective of medical discourse indicates that the body is fragile. If images of the body builder signify strength, the fragility of the other body in a hospital is disembodied. We access this second body in the way the medical machine sees it. The technology that maps our bodies, sees what we cannot see with our eyes and measures the body in statistics juxtaposes itself against the performative youthfulness and virility of photographs of the body builders. We know from Sukanya’s text that the film is about her ailing father.

‘VAICA 2’ thus becomes a platform to broadcast artists’ cinema and video works, away from other conventional broadcasting networks such as television, cinema halls, OTT platforms, film clubs or film festivals. To conclude, I’d like to cite the example of the website, vdrome.org by Mousse Magazine that has developed a successful online curatorial model since 2013 ‘to investigate and promote the relationship between cinema and contemporary art via an online platform that offers regular, high-quality screenings of films and videos by international visual artists and filmmakers’. Erica Balsom in After Uniqueness: A History of Film and Video Art in Circulation articulates the position that Vdrome takes on the internet by saying, ‘The site provides a way of exploiting the distribution possibilities of digital technologies without transgressing the attachments to rarity and control that continue to prevail within the art system.’ Though there is much work needed to be done in India in terms of curating for the internet and a system of fair payment to the artists, ‘VAICA 2’ provides an exemplary template for art institutions to consider while embarking on curatorial ventures in digital spaces.

‘VAICA 2: Fields of Vision’, curated by Bharati Kapadia, Chandita Mukherjee, and Anuj Daga, 20 November–18 December 2021.