The colour indigo fascinates me. It has left powerful and indelible marks on the history of so many nations. Indigo is the colour of a rebel fighting for liberation and emancipation of the oppressed, irrespective of national boundaries. You can look for it in the blues music of African slaves or the Blue Mutiny of Bengal.

In the 19th century, Bengal emerged as the biggest producer of indigo in the world. Indigo was treasured for its rich blue colour and also because it was the only natural source of blue. It was called the Blue Gold.

The Indigo Revolt or the nil vidroh was a peasant movement and a subsequent uprising of the indigo farmers against the British indigo planters, originated in a village of Nadia in Bengal in 1859 and was led by the Biswas Brothers. The scar left of the revolt was so deep that not a seed was ever sown in the soil of Bengal after that.

In colour psychology, if we look around in nature, indigo is infinite—from the depth of the ocean to the limitless blue skies. It is the colour of intuition, perception and the higher mind. It helps in achieving higher level of consciousness.

In Indian mythology, the colour indigo appears repeatedly. Shiva, the one with the blue neck (neelkantha), appears to have drunk the poison to liberate the world of its illness; Kali, the destroyer and slayer of all evils, wears the colour of midnight, depicting the endless dark blue sky; and then the blue god, very illusive like the dye itself, Krishna—Ghana Shyam, the epitome of liberation. The eruption of the Bhakti Movement in Nadia led by Sree Chaitanya broke the shackles of the society and liberated the oppressed, and Krishna became the path to salvation, from advaitavada to the celebration of Radha and Krishna. We could say the first seeds of women liberation were planted.

Rabindranath Tagore, inspired by Padavali Kirtan, wrote ‘Maran re tuhu mamo shyam saman’ where Radha says death is shyam and union with eternal love. Death imparts immortality. The colour indigo remains deeply embedded in our subconscious through Bengal’s history, culture, and philosophy.

My tryst with indigo started in the year 2004, when I started to search for indigo dyeing in Bengal and realized that it was long dead and that no one had any reference of the techniques and traditional dying methods. All that remained were few very obscure ruins of indigo factories in Nadia, Bengal and some buildings in Kolkata like the Tollygunj Club, an indigo planters house, the J. Thomas and Company’s building called Nilhat where they used to auction indigo for the East India Company, and the model of the indigo factory at the Indian Museum in Kolkata which actually has pieces of indigo cakes dating back to that time. What had not died out was the story of indigo, oppression, starvation, and the myth of indigo plant spoiling the soil and making it unsuitable for cultivation.

Thus my quest began and the initial objective was to obtain the indigo cakes. Surprisingly, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu were still growing, farming, and extracting indigo on a commercial basis without their cultivable land getting spoilt. The next step was to get an expert who could come and train the villagers to dye with the indigo cakes. After many experiments, finally, in the year 2006, we got ready a small collection of natural indigo textiles in order to participate at the International Conference of Natural Dyes organized by UNESCO in Hyderabad. Here I was introduced to a whole world of natural dyers and realized the importance and the deep historical connect of Bengal and indigo, and its impact on communities.

It was a strange connection. I was working in Nadia with the handloom weavers. The land which saw the rise and fall of the indigo empire in India and was so scarred by history that even after so many years it was not ready to heal and move on. So, indigo had to be the healer and the liberator once again and through this journey Bengal had to claim back its rightful place.

Here I need to mention a couple of people who have had a deep resounding impact on me and even today are a constant source of inspiration. In 2001, I was first introduced to Mrs Amrita Mukerji founder of Sutra, an NGO to raise awareness of Indian textile, and her amazing African indigo collection. Subsequently she gifted me the first batch of indigo seeds to grow.

The UNESCO conference was decisive where I was introduced to Charllotte Kwon of Maiwa, who later came and stayed in the village teaching the weavers how to create various indigo natural vats reviving old recipes, and host of other natural dyes, and met Jenny Balfour-Paul, the ultimate authority on indigo whose deep passion is haunting.

It is important to mention ‘Weftscapes’, a contemporary textile exhibition at the Serendipity Arts Festival held in Goa in December 2019. The scope of this exhibition was to explore the aspect of our country’s wide textile heritage and tradition of weaving and dyeing through the versatile and unique jamdani technique of Bengal and the story of indigo. The idea was to tell the story of modern times and within it, the story of the Indian artisans who live under the shadow of beautiful textiles of the past which, unfortunately, don’t motivate them as they are constantly compared to some glorious past while refused to be considered as ‘living traditions’.

Three traditional aspects of Indian textile traditions came together to give shape to this exhibition.

1. The concept of weaving a finished garment on the loom. Whether it is saris, dhotis, shawls, dupattas, etc., traditionally in most cases, it was as a finished piece once off the loom. The group of weavers that worked on this project are traditional sari weavers.

2. The story of indigo and its traditional recipes of organic vats, made from bananas, dates, lime, and henna. All the different vats gave different shades of indigo.

3. The traditional extra weft technique called jamdani. This technique was also called loom embroidery where the versatility of the craft allowed the weaver to embellish the cloth with deft twist and turns of a discontinuous extra loose thread called the extra weft to create patterns and butis, to give the plain cloth a more ornate feel.

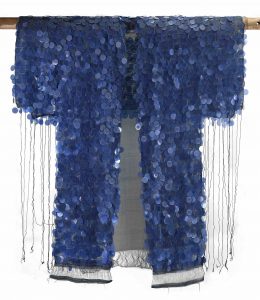

All the pieces of the exhibit were of the same size and shape of a robe or more like the form of a kimono. The shaped garment was drawn to full size on a sheet of paper and traced on the warp threads following the same principals of the jamdani loom and the shaped garment was created with the help of the cut shuttle technique, another traditional weaving technique of Bengal where they would use three weft shuttles to create the bright red borders of the gorad sari. Jamdani or the loom embroidery technique was used to add ornamental value to the surface of gorad sari using non-traditional extra wefts. Different elements like copper wire, ghungroo, felt circles, silk organza bits, fabric cut-outs and strips, metal pipes, French bullion, plastic sequins, and metal beads were threaded and made into yarns and then used as discontinuous supplementary extra wefts for the jamdani. Breaking away from the norm, the idea was to explore the versatility of this craft and to create contemporary pieces that challenged the whole idea of looking at a community and a craft from a traditional eyeglass.

So the choice of colour was quite obvious and could be none other than indigo, the rebel. Various shades of blue obtained from the different vats created depth and acted as an excellent leveller to so much happening on each surface of the garment and brought it out united as a whole. It beautifully connected the history to the present and brought out the essence of this project. It revived old lost recipes but understood the relevance in the modern context. Most importantly it liberated the voice that had got weighed down by its famed history and heritage.

The indigo colour signifies awakening, and coincidently during the last leg of the project, the community wanted to go back to growing indigo. In the history of Bengal no farmer had sown the seeds of indigo ever since the Blue Mutiny. Finally, on March 26, 2020 when the entire country was witnessing a reverse migration of people from cities going back to their villages and farm lands in search of shelter, food, and solace, the first seeds of indigo was sown in Nadia, West Bengal.