Two works come to mind when one visits the exhibition ‘Small Histories: Memory as Practice, Memory as Ethics’, at the Ganges Art Gallery, Kolkata, curated by Amritah Sen and Kurchi Dasgupta, from 23rd June to 2nd July, 2018. The first is a book titled The Ethics of Memory by Avishai Margalit and the second, an essay, “Entering the Flow: Museum between Archive and Gesamtkunstwerk” by Boris Groys. The exhibition is eponymously based on the subject of history, and subsequently attempts to explore the idea of ‘memory’ and the ethics of it.

When we talk about memories, we inevitably think of our relationships with others in the past. Through our shared memories we build close knitted relations with our relatives, neighbours, friends and families. Margalit’s book, which discusses the various nuances of relations, elucidates as to how ‘the past’ plays a key role in making possible various kinds of relationships. He considers the list above as ‘thick’ relations which are ‘truly ethical’. On the flipside, we also foster ‘thin’ relations with strangers, people with whom we share nothing except a common humanity. To sum it up, the ethics of memory is the very act of remembering (the victims). For instance, when a social evil threatens to obliterate our shared humanity, memory is the tool with which we ought to fight. We must remember them through history books, stories, photographs and letters. Margalit’s morally powerful work, drawing on the resources of Western philosophy and religion, offers a penetrating observation of the human situation of our times when the proliferating atrocities leave us paralysed. In such a time of crisis, memory acts as a force which becomes less reconciling and more revengeful.

‘Small Histories’ wants to explore many things including regional histories, ethics of personal memory and various positionalities and promises to “… take a committed look as artists into the past and the present from an unforeseen future scenario” but ends up at an indefinite point with a frail presentation. One of the many things it misses is the ‘healing idea’ which Margalit’s book emphatically suggests will engage us collectively – i.e., those who care about the very nature of our bonding with others.

Groys’ essay, on the other hand, talking about the idea of archive, clearly highlights the role of the curator, distinguishing him/her from the role that a commercial gallery plays in the display of the exhibits. The commercial gallery by way of protecting art works from temporality (by procuring, preserving, segregating art works from touch) de-historicises them. Subsequently, the exhibition space turns out to be ‘neutral’ and ‘anonymous’. A curatorial project, on the other hand, inscribes art works to the spatiality where the exhibition is in display, thereby, creating an orchestration between the work and the space. ‘Small Histories’ misses this orchestration vitally despite being a curatorial venture, and subsequently emerges as an accidental space where the works of various artists are clubbed arbitrarily as if ‘wandering through the material world’. The collective strength in them, therefore, dissipates without answering certain imminent questions. For instance: why should we explore memory? Why should we remember people, culture, history we have lost? Despite facts being undisputed, why do people of diverse group interpret things differently?

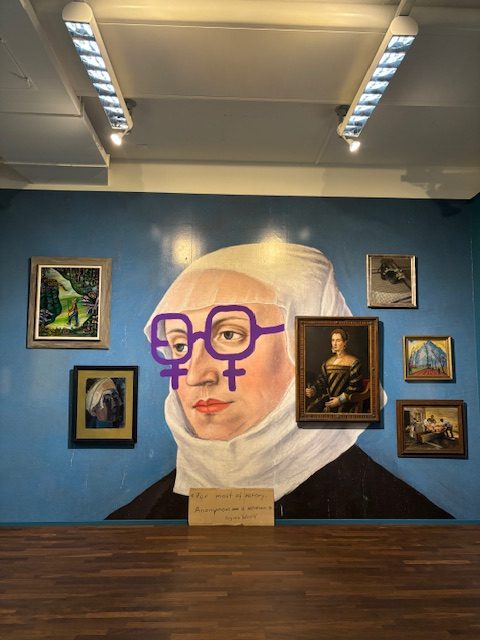

The exhibition features 13 artists from various countries across the Asian subcontinent: Arpan Mukherjee, Debnath Basu, Sumona Jana (India); Mehbubur Rahman, Najmun Nahar Keya (Bangladesh), Ashmina Ranjit (Nepal); Huma Mulji, Marium Agha (Pakistan), Janani Cooray (Sri Lanka), Kunzang Wangmo (Bhutan), Shamsia Hassani (Afghanistan), Thayitar (Myanmar).

Janani Cooray’s take on the identity, ethnicity, power and subjugation of marginal race is conceptually sound, however, her performance across the streets in a dress cut out of foil and entwined with barbed wire fails to create any impact on the viewer. Ashmina Ranjit’s headless sculpture dressed with sanitary napkins is a passé. Shamsia Hassani’s miniature drawings superimposed on photograph’s of Afghan iconic remains and architecture is a trenchant comment on the human situation; Whilst Arpan Mukherjee’s photographs mirroring their corresponding negatives of a forlorn tree and a dilapidated house and Mehbubur Rahman’s soundscape of ambient noise are evocative and nostalgic, it becomes difficult to ascertain their purpose. Despite presenting several episodes in the past few years, the main aim of this ‘ongoing project’ remains ostensible, out-shadowed by the maxim on the invite, which proudly heralds: ‘Bringing South Asia Together in Kolkata’. However, the very idea of featuring such a number of earnest and yet nearly forgotten art practitioners is undoubtedly a laudable effort.

‘Small Histories: Memory as Practice, Memory as Ethics’, curated by Amritah Sen and Kurchi Dasgupta, 23 June – 21 July 2018, Ganges Art Gallery, Kolkata.

All images courtesy: Ganges Art Gallery.