A retrospective perhaps does not always mean looking back at an artist’s entire opus after his death, or a much later phase of his life. It also helps redefining the present stand of the contemporary practices, allowing access for a re-evaluation.

‘Bikash Bhattacharjee: A Retrospective’, organized by the Emami Chisel Art, Kolkata from 17th August to 9th September, 2009 and at Vadehra Art Gallery from 6thOctober till 5th November, 2009 made such re-evaluation possible, raising certain questions too. Does a retrospective then shed light by adopting a historical perspective on the current art practices? How does it offer us a position in our history of art practice? How does it relate us to such a chain of creativity?

BikashBhattacharjee (June 21st, 1940 – December 18th, 2006) belonged to that genre of artists in Bengal who wanted to explore the deeper level of reality through a different path altogether. One of the most prolific realists of Bengal, he had entered the art scenario during a time when European Modernism had reached its culmination. Despite it, the artist had persistently stuck to the pre-modern modes of picture making, largely following the European Great masters such as Rembrandt and Degas as his models, nullifying the Modernist taboos of ‘meticulous representation of visual reality to any reference to the world outside the picture frame.’ The art critic ManasijMazumdar observes: “From (Satyajit) Ray, Bikash learnt couple of things not only to apply to his own art but also to use as a manual when he would himself make films, as was his cherished ambition. Like Ray, he too was a modernist-humanist.”

Compellingly true as they are, his paintings are underlined with an archival quality, defined by a sense of the perpetual. There is a marked classical reticence in all his portraits and still-life. Mutilated body parts disjunctively and uninterruptedly continue to dwell in time, as though they emerge out of nowhere. Bhattacharjee’s works speak of the dehumanized, the tortured, debased specimens of humanity. They speak of the anonymity of human condition. On the other hand are his lusciously rendered women – the idealized; the promiscuous. At times his ideals manifest themselves as goddess Durga, the iconic; at other times they are the commonplace and yet exotic.

The show indeed endeavours a historical overview by painstakingly sourcing works from both personal and private collections. The exhibits are divided into four distinct periods, each marking one complete decade, starting from the 1960s through 2000. Each of the periods cover not only some of the noted works by the artist, but also some of the rare masterpieces. Countless studies and preparatory sketches in pencil, pastel, transparent watercolour, pen and ink drawings that not only mark the formative years of the artist in the decade of the 1960s, but also reflect the elements so akin to a specific region and the remnants of colonial schooling. Death of a Hero (1970), a self-portrait of the artist in an orange Punjabi (1970) Lady with Watermelon (1979) and the much discussed Doll series are significant works of the period. An unusual silkscreen on paper, titled Kotha – Jibananda Das (1976) and one of the exhibits that reflects dabbling a little with cubistic forms, however arbitrarily they occur, are interesting deviations marking the experimental nature of the artist. They often reveal a much more edgy side of his works, too. The 1980s are marked with women’s portraits. The semi-nude, dishevelled and unkempt Durga in the Morning (1990), who appears to have woke up to her senses after a night spent with her beloved, whose joltingly mortal, unlike the divine goddess, whose glaring third eye on her forehead retains her cosmic identity; the brooding Portrait of ShambhuMitra (which had appeared on the cover page of the Bengali weekly magazine Desh in 1994) and the rather surrealistic painting Over the Dark Clouds (1997) belong this decade.

The catalogue becomes an invaluable source of documentation, indispensable to a study of the artist. It comprises of an exhaustive list of facsimiles of reviews and writes ups, gallery invitations and press releases of the shows in which the artist had participated during his lifetime. The last few pages of the catalogue become an archive of photographs of treasured moments in the life of the artist.

Pranabranjan Ray’s poignant biographical essay sheds light on an unexplored Bhattacharjee. Ray begins from his getting acquainted with the artist from the earliest days of their friendship as he knew him, and goes on so far as bringing out with his consummate skill the rise and fall of a master, stating with candour what may seem as revelations. A personal account by artist SanatKar and another by the art critic ManasijMazumdar speak about the practice of the artist, while a fourth one by Amit Mukhopadhyay delves deeper into the artist’s psyche as a modern man and traces the paradox of the existential dilemma which necessarily wants to strive forth breaking all hurdles. Mukhopadhyay looks back into the recent past through Bhattacharjee’s opus in order to reevaluate our progress and ‘how far’, so to speak.

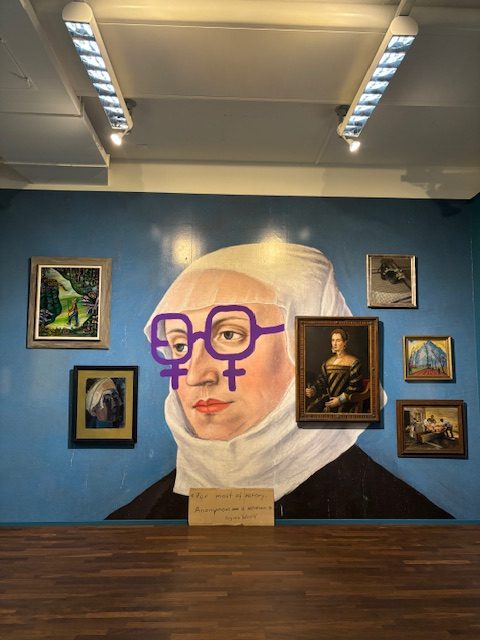

Image Courtesy: Emami Chisel, Kolkata.