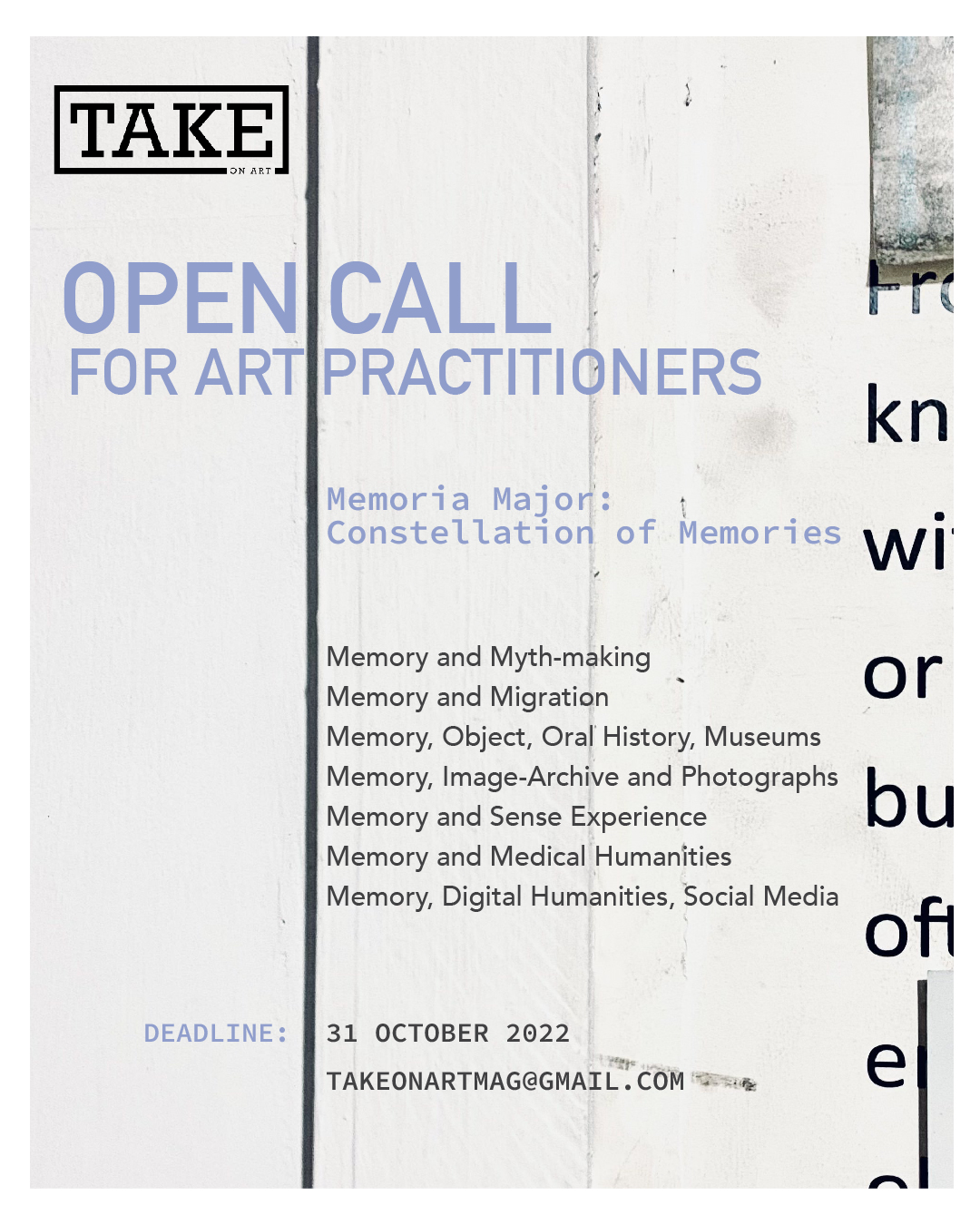

Open Call for Art Practitioners — Memoria Major: Constellation of Memories

TAKE Memory / Issue 28, 2022

Themes:

Memory and Myth-making

Memory and Migration

Memory, Object, Oral History, Museums

Memory, Image-Archive and Photographs

Memory and Sense Experience

Memory and Medical Humanities

Memory, Digital Humanities and Social Media

Deadline: 15 November 2022

Write to takeonartmag@gmail.com

Concept Note

“Memory is handed down, history is written down… memory is personal, history dreams of objectivity….” — Maria Stepanova, In Memory of Memory

When the events of the twentieth century unfolded—the cartography of national borders, political revolutions and neo-liberalism—they prompted the desire to remember the historical past in the shape of archives, memoirs, museums and monuments. The ensuing experience of anxiety, belonging, displacement and loss -a continual practice to haunt everyday lives – are closely tied to the terms: collective memory (Halbwachs 1925) and cultural memory (Assmann 1995). The ‘fluid’ memory against the historical ‘data’; ‘broken’, non-linear time versus chronological ‘order’; central ‘reality’ distinct from peripheral ‘reminiscence’ contribute to amplifying the voice of resistance to the grand metanarrative of nation-building exercise. In the same spirit, the world of representation, even when navigating the spatial-temporal axis to trace the becoming of the self, could not escape the pressing concerns around the political issues of identity and institutions.

Closer home, the Indian Subcontinent is a recurrent witness to the rise of distorted facts as a way to establish majoritarian dominance over history. It triggers a unidimensional view of the past which is antithetical to its imbricated layers. The constructed account of the events—1947 Partition of the Indian Subcontinent, communal violence, manipulated social reality, cultural intolerance—has set into motion the interest towards the necessity to listen to both personal and collective memory. The memory quotient is not limited to the description of the events and existence; rather it attempts to engage with and challenge the classical historical material (da Silva 2017). As the circuits of memory lead the network of entanglement, it disturbs what Rancier (2004) has defined as the ontological trap. Towards this end, the flecks of memory shed a light on the narratives populating the margins only to expand the pluralistic environment.

The forthcoming edition TAKE Memory emerges from this context to identify the ground of inclusive perspective on the lived experiences by extending the critical inquiry on the constellation of the arts, archive, food, monuments, memorial, object, visual culture and technology, to name but a few. Even when the 1947 Partition is largely touted as the entry point into the concept of memory, especially in the Indian Subcontinent, the current issue dedicated to Memory envisions the founding event as the fecund site to both draw on and depart from it to dwell a step deeper into the subject. Additionally, with the surge of digital media, trends and posts, memory as a concept has acquired a new intangible meaning i.e., communicative memory (Erll 2016).

Irrevocably, the overarching tendency to anchor a unified and official history in the times of the 75th year of 1947 Partition serves as a timely backdrop to offer an access point to the assemblage of diverse ideas and distinct exploration of the presence of a flourishing field of cultural and personal memories in South Asia. In doing so, TAKE Memory is an endeavour to expand the many meanings entailed in the discipline of memory.

Themes

Memory and Myth-making: Memory and mythology are both cultural and are separated by arbitrarily assigned truth claims, but the boundary between them is porous. The ambiguous position of memories—lying somewhere between fact and fiction—must be mediated in order for memories to gain materiality (Assmann, 1995). Myths are important mediators that lend symbolic, visual and cultural meaning to flitting memories. Myths, metaphors and even superstitions emerge from oral history and are embedded in fantasy. As they draw a reference to foundational events, both real and imagined, myths serve as a means for communities across the swathes of history to come to terms with, and preserve their origins, belief systems and its memories.

Memory and Migration: The 1947 Partition came at the cost of one of the largest forced migrations of the twentieth century. Yet, the people engaged in high politics have kept the consequences of faulty lines of division at bay. While standing in antithesis to linear historical narratives of the Partition, the weaver’s diary (Pandey, 1991), comprising private memories, personal anecdotes and broken narratives, silhouettes the culture of the visual arts of 1947 Partition-led migration.

Memory, Object, Oral History, Museums: The palpable necessity to document the violence and trauma experienced during the time of 1947 Partition was met with the urgency shared among the scholars, before the population of the first generation of the forced migration withered. The personal memories collected through the methods of oral interviews as well as the family objects offer a glimpse of the pangs of separation and dislocation—the view lost from pages of the official history of the independence of India. Despite the soaring high politics of independence, the authors gauge the other alternate methods of documentation and museums making practice on the 1947 Partition.

Memory, Image-Archive and Photographs: The troika of production, documentation and preservation catapults the archives and the archivist—in our context, the archives of photography—into a site of historical inquiry, which asks for its extrapolation in terms of what is value worth of reminiscence and silence. Viewed as a social construct, a single document claims its historical context, but pondering upon its need to be constructed, and contextualising its times of making, make it an archival document. To dig deeper into the question of memory and image archive, the imperative to reimagine the conventional notion of photographs as a reservoir of framed memory shall be probed.

Memory and Sense Experience: Visual order that perseveres in traditional and canonical art relies on the power of the objectifying, ordering gaze. (Irigaray qt. In Owens, 1983) While vision is the seat of clarity and reason in Renaissance iconography, the other senses are bodily and material; abject and othered. It is through these embodied sense-perceptions then, that the alternative spaces of memory, fantasy and imagination demand legitimacy. Just as the notion of history distorts and falls apart under the weight of the inquiries made by memory, dominance of visual art can be thwarted by contemporary explorations into auditory, olfactory, gustatory and haptic systems.

Memory and Medical Humanities: Scars, wounds and phantom limbs are remnants of trauma and sickness—memories of embodied loss, permanently etched onto the body. This involuntary experience of pain, say, due to a terminal illness, disempowers and traumatises the individual by robbing them of their agency. However, the road to recovering subjecthood goes through the confrontation with and reappropriation of this memory—both of which have the potential to be attempted by the acknowledgement of the ailing, medicalised body and its physical and psychological pain through artistic expression.

Memory, Digital Humanities and Social Media: The intergenerational memory in the current times is not limited to the circulation of material objects or oral narration when digital platforms and social media facilitate novel archival strategies and means of remembrance. Besides, collective and cultural, the term communicative is suggested to reconfigure the contours of memory. To mention, the “floating gap” widens across the time remembered in the algorithm of the communicative memory and emotive materiality of cultural memory. The conventional ways—tactile stimulation and visceral touch—to measure the passage of time are now response-sensitive to the flow of data and real-time operation.

Submission Details

+ Artist proposal (500 words)

+ 15 images to support the proposal (high resolution + 300 DPI)

+ Bio-note (200 words)

+ A motivation letter indicating your interest in an artist’s book and book making (400 words)

Frequently Asked Questions

—Who can apply?

The artist and/or art historian at any stage of their career can apply. The call is open for individual artists as well as collectives. There is no age-limit. The applicant could, but not necessarily, have a body of work in an advanced state, which is yet to be completed.

—How expansive should the work be?

There should be no more than 30 pages, and the work should ideally be reproducible in print.

—How will TAKE support you?

TAKE will cover the printing/publishing cost. (The grant does not include purchase of equipment(s) or staffing or outsourcing costs.)

—What are the distribution platforms?

The final book will be distributed worldwide and available for purchase at TAKE website. Additionally, the selected artist(s) will be promoted on our website and social media handles.

References

ξ Assmann, Aleida. ‘Four Formats of Memory: From Individual to Collective Constructions of the Past’, in Cultural Memory and Historical Consciousness in the German Speaking World Since 1500, eds. C. Emden and D. Midgley, Bern: Peter Lang, 2004.

ξ Assmann, Jan, and John Czaplicka. “Collective memory and cultural identity.” New German Critique 65. 1995, pp. 125-133.

ξ Bergson, Henri. Matter and Memory. London and New York: George Allen & Unwin Limited, 1929.

ξ Erll, A. Memory in Culture. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

ξ Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory, trans. L.A.Coser, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

ξ Pandey, Gyanendra. “In Defence of the Fragment: Writing about Hindu–Muslim Riots in India Today”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 26, Nos. 11-12, 1991, pp. 559-72.

ξ Rancière, Jacques. “Who Is the Subject of the Rights of Man?” The South Atlantic Quarterly 103, no. 2, 2004: 297-310.

ξ Stepanova, Maria. In Memory of Memory. New York: New Directions, 2021.

Please download concept note in PDF format here.