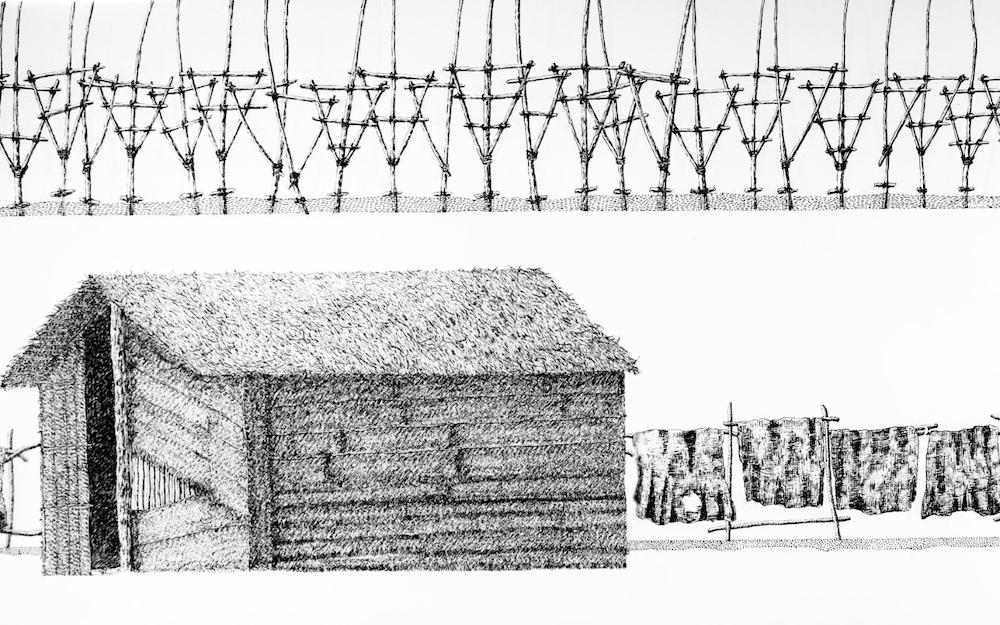

The Present is a Ruin Without the People, Ruby Chishti, 2016. Presented at Lucid Dreams and Distant Visions: South Asian Art in the Diaspora. Image courtesy of the artist.

It is tempting to fall into the trap of making sweeping statements when it comes to South Asia. The appropriation of the concept in allusions to the former conveys the legacies of colonial histories or the penchant to hang on to old, romanticised versions of a pre-Partition undivided sub-continent. It is futile to wish away the existence of borders or the deep-rooted schisms that engulf the region thanks to the Partition; equally, it is prudent to accept that new equations have emerged in different parts of the sub-continent with China, the US, and Russia, and are here to stay.

Erstwhile narratives around South Asia have outlived their utility and need to be re-examined using a more forward-looking approach to where we can go from here. Doing so collectively and collaboratively might enlarge the process of regional development and welfare beyond economics alone to encompass the arts and our rich cultural histories. Moreover, a younger, ambitious population, and diaspora unencumbered by this baggage of old histories, can become valuable allies in the process.

So. what is South Asia today? With 22% of the world population spread over 7% of the world’s land mass, the region boasts a mix of contradictions, with an average per capita annual income of merely two thousand dollars, a fifth of neighbouring East Asia, and one-twentieth the level of high-income countries. Juxtaposed against the sluggish growth rates and, in some cases, de-growth in Europe and large parts of the West, South Asia is expected to grow faster at just under 6 percent. However, it is important to note that not all countries in the region are growing at this pace, and three—Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka—are all grappling with serious economic and political crises.

As the only centre for Asia Society in South Asia, many reasons spur us into action in building a more holistic understanding of modern and contemporary South Asia, focusing on what can be rather than what has been. There is a common set of developmental challenges that transcend borders in this region, be it terrorism, displacement, air pollution, the economics of energy, vaccine inequity, or the climate-water security nexus outlined by the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI). Changing weather patterns continue to reshape the hydrological landscape of South Asia. The 10–30% erosion of mass forecasted for Himalayan glaciers by 2030 is likely to have a cascading effect around sustainable access to water. This interconnected web of issues makes it important to build a framework of cooperation outside the realm of politics: a business-to-business and people-to-people connect that begins to acknowledge this reality and pushes ahead towards navigating some of these challenges collaboratively.

The discourse on South Asian art is deeply intertwined with the larger paradigm of the Global South, with artists vividly showcasing the socio-political, economic, and cultural dynamics of the region. Here, despite divisive geopolitics, there exists a vocabulary that speaks to common concerns and opportunities, and can be a powerful tool to both understand and reimagine a more contemporary conceptualisation of South Asia.

Installation from Six Degrees of Separation: Chaos, Congruence and Collaboration, Image courtesy of Khoj Studios.

Jasmine Nilani Joseph’s reflections on displacement in her studies on abandoned spaces and their sense of emptiness in Jaffna, resonate with Joydeb Roaja’s ‘Lake of Tears’, an installation at the Dhaka Art Summit in 2023, that depicted the displacement of over 100,000 members of the Chakma community. Both build a visceral understanding of refugee issues in one of the largest regions to be impacted by this. In recent years, a steady rise in regional residencies, biennales, and art summits has provided open spaces for artists across the region to contribute to these shared narratives. Exhibitions like Lucid Dreams and Distant Visions organised by the Asia Society Museum had contemporary artists from the South Asian diaspora exploring notions of home and issues relating to migration, gender, race, and memory across mediums and aesthetics. Six Degrees of Separation: Chaos, Collaboration and Convergence curated by arts organisations like Vasl (Karachi), Theertha (Colombo), Sutra (Malaysia), Britto (Bangladesh), and Khoj (India), showcased over 45 projects conceived and produced by artists in residencies organised across the subcontinent since 2001. More recently, the Kathmandu Triennale 2077 was informed by discourses of decolonization, migration, and displacement, redefining the parameters of art beyond a Eurocentric canon.

The role of curators then becomes crucial to navigating this discourse in a nuanced, inclusive, and forward-looking way. Raqs’ proposition to consider curation as a way of drawing itineraries rather than inventories, and producing milieus rather than themes, can be one way of doing this. With contemporary artists spotlighting ‘thornier’ issues that compel difficult discussions, curators and museums can play a pivotal role in representing them and activating wider discussions through public programmes, foregrounding their creations as important commentaries on the societies we live in. Democratising access to art is also critical to harnessing its ability to catalyse changing mindsets. Sharmini Pereira, Chief Curator of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Colombo, is consciously making art more accessible and inclusive. Curatorial text accompanying each work in the museum and its messaging on social media is inscribed in Sinhalese, Tamil, and English. Unconventional exhibitions like Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular, co-curated by Iftikhar Dadi and Roobina Karode, provide valuable perspectives on how modern and contemporary South Asian art engages with popular culture, including questions of politics, public space, and identity. The opportunity to broaden curatorial discourses yet more by encompassing explorations in craft, art, history, and design is yet another trope that needs more curatorial attention. Sabih Ahmed, Curator of the Ishara Art Foundation, encapsulates this well in highlighting that the “impact of artistic and curatorial work can be measured by how it contributes to new ways of thinking about history and the present.”

Lockdown Series #3, Jasmine Nilani Joseph, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Lockdown Series #3, Jasmine Nilani Joseph, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Amidst the underlying dichotomies and contradictions inherent in the region, an unmistakable commonality connects communities in South Asia and the diaspora – the intersections of culture, language, customs, and traditions make it appealing to congregate around curated cross-border cultural exchanges. In the forward construct we speak about, we need to engage these communities of artists, curators, collectors, academics, industry leaders, and the young even more, through scholarship, discourse, and personal interactions. Our caravans across the region have renewed our hope in the possibilities of dialogue and exchange to serve as a catalyst towards a South Asia that is more inclusive, integrated, sustainable, and peaceful. By enlisting communities as allies and champions of this cultural renaissance, we become custodians and owners of this aspirational reality.