Abstract: Working with the Jesuit social communication organization Chitrabani in Calcutta, a group of Bengali-leftist photographers aimed at positive social change by photographically documenting the everyday drudgery of the poor and the middle-class Calcuttans from the late-1970s through the early 1990s. Their commitment to social change manifested through 4000 black-and-white as well as colour photographs that provided a sense of self-worth to their subjects, irrespective of their socioeconomic standing, and emerged as a visual critique of the postcolonial situation. These traces of documentary realism afford a glimpse into the urban experiences that conditioned them, while also providing an insight into the relationship between Catholic Social Thought and documentary photography in postcolonial South Asia.

[H]ow can photography, a relatively expensive medium, be useful or at least relevant to the development needs of the country or, shortly relevant to the poor?[i]

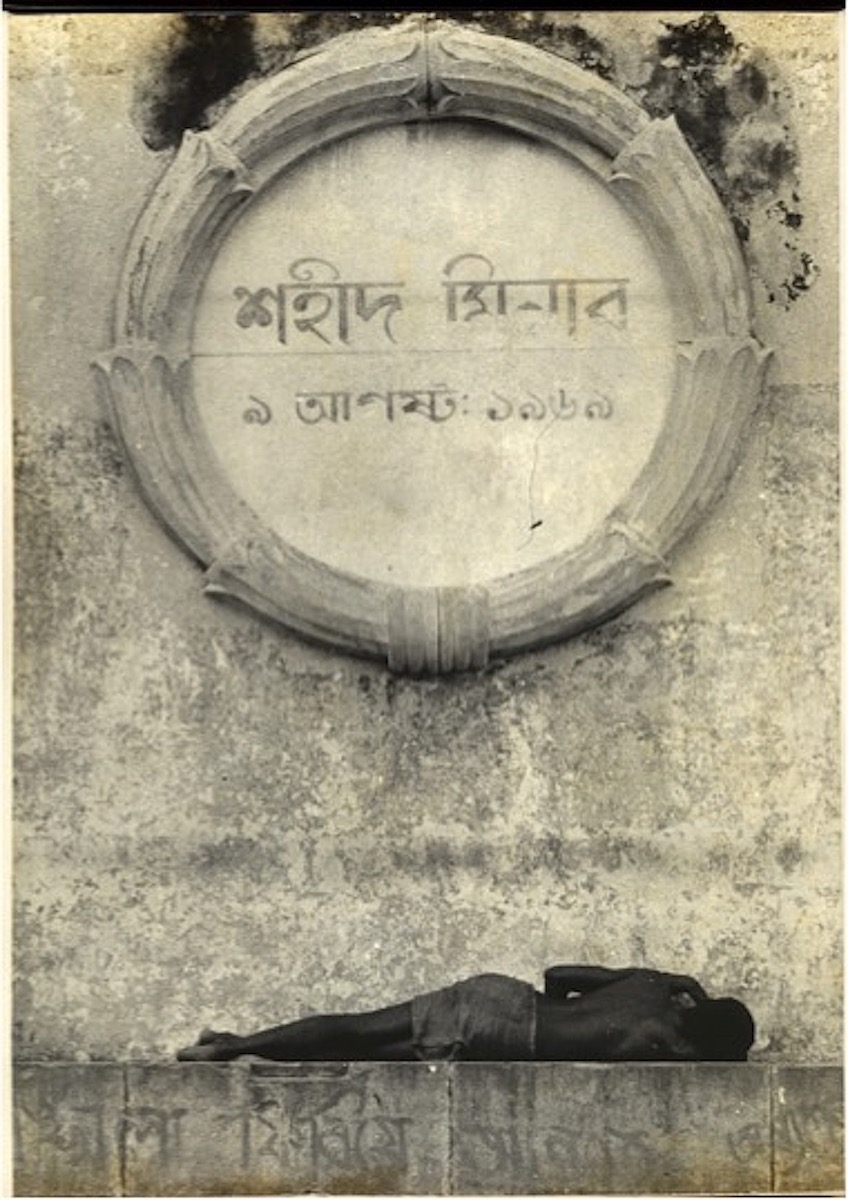

Titled Shaheed Minar and made by Ardhendu Chatterjee in 1977, the photograph in figure 01 depicts a rounded medallion with an Indic script, a scantily clad man lying underneath, and a faded graffiti, also in Indic script. The script within the medallion reads Shaheed Minar, a Bangla phrase translated as monument of martyrs, followed by a date, 9 August 1969. The text in the medallion together with the male body is meant to be an ironic contrast alluding to an idea of poverty as social martyrdom. The contrast of the man and the medallion is enhanced by the faded graffiti fragment that reads “…srinkhala firiye aante” in Bangla, translated as “…to bring back order” and is undoubtedly a portion of a slogan used in the electoral campaign that year. This photograph literally portrays the post-colonial Indian state’s failed promise of social welfare; the poor were not removed from the public sight, but simply left to themselves as if they did not exist. The fragmented graffiti phrase indicates a demand to institute “order”. Within the visual space of the photograph, “order” can be read as a social matrix that would not overlook the poor. In one sense, like the fragmented graffiti, the photograph calls attention to a social problem without offering a particular solution. In another, the photograph itself complete the graffiti fragment and affirm the dignity of the under privileged my making them visible; the photograph is a tactic “to bring back order”.[ii]

This photograph is one of the 4000 documentary photographs from the series People of Calcutta (1977–91) that critically reflected on the ordinary and the everyday urban and peri-urban experiences of people of diverse class, caste, religion, ethnicity, gender, and age. In the long and the illustrious history of photography in Bengal, People of Calcutta stands out as a unique effort in making non-commercial and socially-committed documentary photographs whose avowed goal was to “give faces to the faceless”.[iii] Arguably the longest running photo-documentary project on the city, it was organized by the Jesuit priest of Canadian origin and founder-director of the Jesuit social communication organization Chitrabani, Fr Gaston Roberge, SJ. It began after the end of the Emergency (1975–77) and involved twenty three Calcutta-based left-leaning photographers, including Ardhendu Chatterjee over a span of almost three decades.[iv] Majority of the photographs were taken in two concentrated spells: photographs of the urban poor were made during 1977–79 under the title Shaheed Minar (Monument of Martyrs), while images of the middle class bhadralok, under the title Ghare Baire (Home and the World), predominated during 1989–91. Even though the two phases focused on different social classes, the team’s perspective on human struggle and their focus on everyday lives of ordinary Calcuttans in the backdrop of a socio-political and economic flux united the two phases into a coherent project. This elaborate visual repertoire, in black and white and in colour, reflected the city’s local ethos, while also drawing on internationally circulating discourses on socially conscious documentary practices and Catholic Social Thought, as Chitrabani photographers reinterpreted and represented postcolonial Calcutta. It challenged the popular narrative of a decaying postcolonial city and the question of development in post-independent India by visually documenting resilience of the underprivileged, marginalized and ordinary Calcuttans.

Shaheed Minar, the first phase of the People of Calcutta, took its name from a prominent imperial victory column located in the heart of Imperial Calcutta, with balconies near the top offering an elevated panorama of the city. Originally built as the Ochterlony Monument in 1848 to commemorate Sir David Ochterlony’s victory in the Nepal War (1814–1816), this tall white imperial column was renamed Shaheed Minar—a Bangla phrase meaning “monument of martyrs”—in 1969 in the memory of the martyrs of the freedom struggle of India. The title Shaheed Minar reinterpreted this iconic public site by offering a body of photographs that functioned as a conceptual vantage point as well as a metaphorical monument to social marginalization. However, the photographs flipped the idea of a panorama and a vantage point. Unlike the conventional panoramic view from Shaheed Minar’s balcony, which creates distance by elevating the viewer above the city, the photographs of the series were to bring the photographic subjects and viewers closer. The photo-documentation emphasized not the Calcutta of the towering achievements of which the Monument was a signifier, but the Calcutta that embodied ordinariness and marginalization in the Unintended City.[v] Chitrabani’s newsletter described the series as a monument, as an emblem of congregation of the city’s marginal people:

‘Monument’, (that is, a ‘reminder’) bearing witness to the fact that Calcutta consists largely of people who suffer, martyrs of an unjust order, who keep on with the business of existing with a simple, unpretentious, heroism.[vi]

Finally, the appellation was significant because the photo-documentation was trying to metaphorically claim anew, in the name of the people, a piece of symbolic architecture that was built as an imperial icon and was later claimed as a nationalist monument by the postcolonial state.

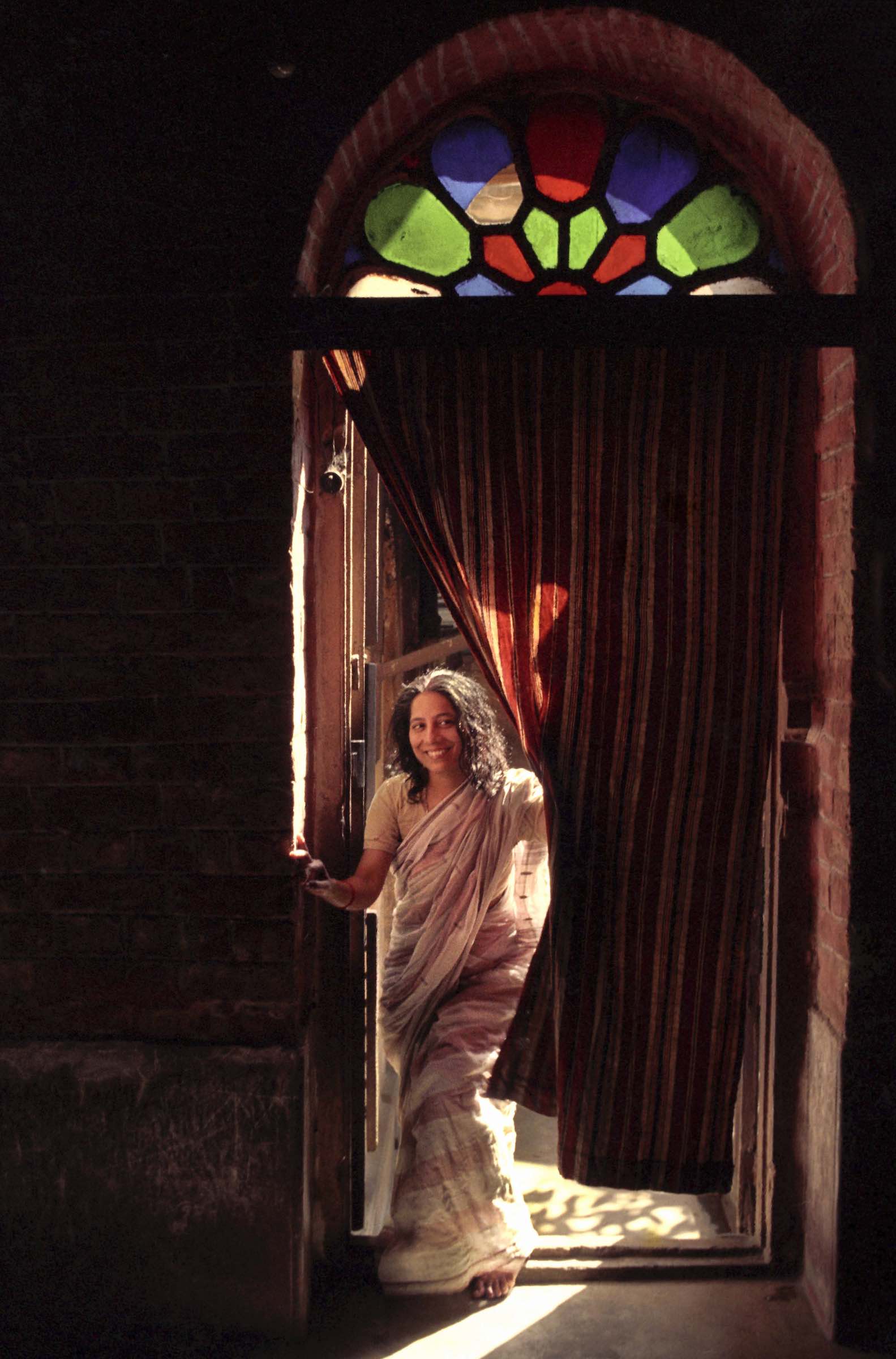

Unlike this explicit deliberation in naming the first phase, the formal naming of the second phase was somewhat accidental. Roberge’s choice of Ghare Baire (The Home and the World) as the title for the second phase was inspired by one of Shilbhadra Datta’s photographs (Figure 02) that had uncanny similarities with auteur filmmaker Satyajit Ray’s design for the latter’s film of the same name and Ray’s own thoughts on Datta’s photographs. It alludes to everyday aspects of middle-class lives and hardships, which Chitrabani wanted to document. However, the style Datta adopted for Ghare Baire—to emphasize the minutia of the everyday—was significantly different from Chatterjee’s approach during Shaheed Minar. Chatterjee opted for the style of street photography, while Datta preferred nuanced staging.

In making these images, photographers at Chitrabani were inspired by an array of visual practices, ranging from fiction and non-fiction cinema—including Bangla fiction films, documentary traditions of the kino-pravda, cinéma-vérité and works of documentary film theorist John Grierson—to American social documentary photographs including Firm Security Administration images, the street photography of the Magnum and specially Henri Cartier-Bresson, as well as prominent Indian photographers like Raghu Rai and Raghubir Singh. Brian McDonough, a visiting social worker-photographer-lawyer from Montreal (Canada) and, later, a contributing photographer to People of Calcutta, offered an intensive seminar course on documentary photography in May 1977 and Chitrabani’s library had a wide range of books on photographic practices in the USA and in Western Europe. However, photographers at Chitrabani had the closest affinity with the tradition of “concerned photography”—a term that came as a corollary to the establishment of the Fund for Concerned Photography in 1966 by Cornell Capa with roots in the Magnum.

Photographers at Chitrabani documented the drudgery of the everyday, while Roberge wrote extensively on the intellectual background of these images—the multisensory experiences offered by Calcutta, the theology of communication that informed the photographs, and the ways in which photography was to play an instrumental role in positive social changes in the city. Reflecting on the photographers’ urban experience, Roberge wrote,

The city itself is our resource centre and the students [and photographers of People of Calcutta] are encouraged to integrate the various media experiences that the city offers: films, drama, folk media performances, music, dance, exhibitions, radio, television, advertising, seminars, lectures, etc.[vii]

However, the city was a resource centre not only as a vibrant mediascape, but was also as important as a site of articulating the idea of a “people” as historical actors. People of Calcutta began at a time when “the people” and non-elite experiences of the everyday became the focus of critical attention among the Bengali intelligentsia. The Leftist cultural productions in particular are replete with representational forms—including literary, visual and performative—that focused on ordinary people and their experiences of the everyday. One of the markers of the period was the ways in which “culture” became a vehicle for the “political”; for the Leftists, broadly speaking, “culture” became a way of reaching out to subaltern consciousness. Chitrabani was a melting pot of Leftist/Left-leaning creative intellectuals and People of Calcutta was a product of a milieu influenced by the ideologies of the Left and its emphasis on the “peoples’ struggle”. Indeed, majority of the photographers identified themselves with the politics of the Left and at least one photographer was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). The leftist commitment to people was complemented by Chitrabani’s Catholic commitment to human development. After the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) “social communication” became an essential aspect of Catholic discourses with an emphasis on the Theology of Communication. The Vatican II decree Inter Mirifica followed by the papal encyclical Populorum Progressio focused on the development of people through effective use of media of communication and the specific languages used in these two documents resonated in Roberge’s writings on People of Calcutta. According to the encyclical, “man’s complete development” is intimately related to human dignity and personal worth, two notions that guided People of Calcutta, especially during Shaheed Minar. Contrary to economic model of development, realization of self-worth was the foundation of the human development professed by Chitrabani and photography was perceived as instrumental in that self-realization.

The poor Calcuttan is imageless … no ‘portrait’ with which to identify with legitimate pride…. The only images of the poor Calcuttan are those made by tourists … or by development agencies. The image these people make portray the poor Calcuttan as a passive, dependent, incapable, pitiable, frustrated and unruly man, woman or child. While poor people are often forced to be such, they are not primarily incapable of self-help.[viii]

He further continued,

Our (Chitrabani) images show them (poor Calcuttans) as human beings having limitations but also having many qualities. We do not offer these images to arouse pity. We offer them as one would open a family album with trust in [the] onlooker’s readiness to understand others.[ix]

This reference to a family album is significant because it not only referred to a community based on Catholic ideology, but also anticipated the second phase Ghare Baire. Chitrabani’s goal was not to evoke pity, but to elicit empathy and to forge an ethical community founded upon the practices of everyday life. Ghare Baire expanded this ethical community by weaving together the middle-class photographers and their homes with the lives of the poor in a shared space of solidarity and comradeship through their banal experiences of encountering the city. Long Live Revolution by Shilbhadra Datta (Figure 03) is an example of the ways in which aspirations of revolutionary solidarity unfolded in the banality of the everyday.

People of Calcutta was meant primarily for community exhibitions, group discussions, and adult education. Chitrabani produce notes providing the socio-economic data required for understanding the photographs and expected “the persons whom they photographed or at least people of the same class and set” to be the main users of the photographs.[x] Roberge envisioned one of the objectives of the documentation to be the visual education of the viewers, irrespective of their class affiliation. A product of the 1970s social justice ethos, the photographs no longer have the same rhetorical charge and they have not survived in the city’s collective memory. Initially meant to have a wide circulation, these photographs, now remain locked away in a little-known institution in central Kolkata. Yet, the juxtaposition of a group of left-leaning photographers working under the aegis of a Jesuit social communication organization, in the milieu of post-Emergency Calcutta, is a rich moment of art practice in the postcolony that raised questions of class, subjectivity, and agency through the medium of photography.

[i] Gaston Roberge, “The Involvement of Chitrabani in Still Photography” in Collected Works of Gaston Roberge, Vol. XI, (typed manuscript dated 13 October 1992), 169–171.

[ii] I have borrowed the notion of ‘tactics’ from Michel de Certeau. For a discussion of strategy vis-à-vis tactics see Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven F. Rendal (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 34–39.

[iii] Gaston Roberge, interview with the author, 21 May 2006.

[iv] Established in 1971, Chitrabani was the first media studies centre in Bengal. In translating the name Chitrabani, chitra may be picture or image and bani may be words, voice, or sermon. While naming the institution, Roberge, who moved to Calcutta from Montreal in the early 1960s, was inspired by Rabindranath Tagore’s usage of the word to describe cinema. The photographers involved in the People of Calcutta project included Amit Dhar, Anjan Paul, Ardhendu Chatterjee, Ashish Auddy, Brian Balen, Brian McDonough, Claudine Gomes, D.K. Nayak, K. Ghosh, Lewis Simon, P.B. Chaki, S. Chatterjee, S. Mondal, Salil Nandi, Salim Paul, Shantanu Mitra, Shilbhadra Datta, Achinto Bhadra, Sita Sahane, Subrata Lahiri, and Vivek Dev Burman. Many of them went on to become professional photographers working across genres.

[v] See Joy Sen, Unintended City (Calcutta: CRS, 1975). Unintended City is a monograph based on a survey done by Unnayan, a research-oriented activist NGO, and published by Cathedral Relief Society, a Calcutta based NGO operated by/from the St. Pauls’ Cathedral Church.

[vi] “Shaheed Minar” in The Newsletter of Chitrabani, 40 (February 1980), p. 8.

[vii] Gaston Roberge, “Chitrabani: An Indian Experiment in Development Communication,” Educational and Broadcasting International: A Journal of the British Council, Vol: 13 No: 3 (September 1980), p.137.

[viii] Gaston Roberge, “Shaheed Minar”, in Quarterly Journal of National Centre for Performing Arts, Vol. IX, no. 2 (June 1980), p. 21.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] “Still Photography for Development (II) – the Chitrabani Photographs” in Development Communication: The Chitrabani Newsletter, 54 (May 1984), p. 4.