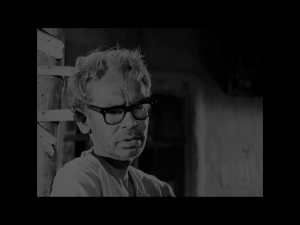

Ritwik Ghatak (1925–76) was one of the most powerful artists to have emerged in post-independence India. He managed to finish only eight feature films and a few documentaries and shorts. Largely ignored by critics and audiences in his lifetime, he has gained wide recognition since the 1980s. Ghatak himself has left some remarkably thoughtful commentaries on his work. His career as a filmmaker, dramatist and intellectual should be judged in relation to his times and to ours to get a sense of the complex image he constructed of our historical predicament. By examining the interweaving of historical experience and re-invoked tradition, political consciousness, and aesthetic form, in Ghatak’s work, one can arrive at general conceptions about art and historicity in our times.

Emotionally intense experience that Ghatak’s films are they are also a reflection on consciousness, nature, and human destiny. They invite us to make connections with cultural pasts and political landscapes, and open up a space for thinking the history of the present. Cinema rarely affords us this adventure of ideation. The modernism that his work embraced did not depend on a tradition-modernity divide, but had an intuitive understanding of the internally heterogeneous modernity that seems to be the reality of most of the world. Ghatak grew up in a Bengal where the 1930s generation of writers and the progressive cultural movement of the following decade provided a fertile ground for the assimilation of international tenets of the arts on one hand, and a renewed engagement with Indian classical and folk traditions on the other. He wrote about his film Subarnarekha (‘The Golden Line’, 1962) that it borrows from the English Chronicle Play in its structure, Bertolt Brecht in principles of representation and Upanishadic imagination with regard to a certain perception of life. Rabindranath Tagore, cited frequently in Subarnarekha, is a constant presence in his films. This principle of recombination is followed in all his work, unencumbered by the fear of loss of authenticity that we find in the current identity-based approaches to culture.

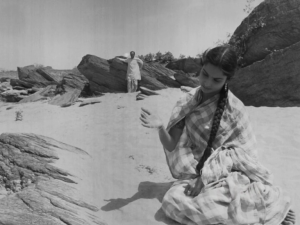

Can artistic practice located in the non-Western world figure a global modern consciousness? Ghatak attempted, quite unlike anyone else of his generation, to develop the experience of the partition of India in 1947 into a general symptom of homelessness. In an essay on his 1961 film Komal Gandhar (‘The Gandhar Sublime’) he talks about capturing the ‘homeless shape of life’. Historians have investigated the violence attending the birth of nations; and we are witnessing right now in the Syrian and Rohingya refugee crises, or in Kashmir, yet another unravelling of the meaning of borders and territory. Ghatak was able to connect individual lives thrown into such upheavals with a sense of consciousness distributed over space and time. His style of composition and use of lenses, his method of figuring the human body in relation to the landscape, the logic of transitions he used in narration, the operatic use of music and performance—all serve that purpose. In Subarnarekha, for instance, a scroll of inscriptions appears from time to time making comments on the story, or just stating that years have gone by. The transition is quietly signposted in the film by someone going insane in the interval, or by news of epochal events like Yuri Gagarin going to outer space. Such punctuations take the story from the confines of the family to a horizon both historical and mythical in its resonances. In the structural principle Ghatak adopts, the image does not simply depict things, it also works as a constellation of thought; the narrative presents allegories of historical shifts. A community such as his, passing through a catastrophe, stands in for communities in transition across the world. This is why it must tell its story in the epic form.

His essays provide perceptive commentaries on his filmmaking; and they show a sophisticated anthropological imagination at work. His interest in Indian philosophy and his use of mythical elements are to be seen as aspects of that imagination. It explains his choice of themes, and the analytical bent of his work. This often caused confusion among left wing critics since mythological or ritual elements were seen as inimical to progressive, rationalist culture. He had to face charges of obscurantism, a serious charge to level against an artist who considered himself a Marxist. On the other hand, the tendency to go beyond psychological realism, even deny centrality to individual consciousness in the plot, created another anomaly at a time when Indian cinema was trying to discover the individual as well as rational storytelling, overcoming mythicized characters and plots. At a time when the new realist cinema, pioneered by Satyajit Ray, was self-consciously marking itself off from the popular romance, Ghatak’s use of melodrama and musical narration puzzled the critics. On the use of music in Indian cinema, he wrote:

(W)e are an epic people. We like to sprawl, we are not much involved in the story-intrigue…We as a people are not much sold on the ‘what’ of the thing, but the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of it. This is the epic attitude. So the basic folk forms … are always kaleidoscopic, pageant-like, relaxed, discursive….

Starting with Bari Theke Paliye (‘The Runaway’, 1959), the family features centrally in the films (Meghe Dhaka Tara [‘Cloud-capped Star’], 1960, Komal Gandhar and Subarnarekha). The family provides the core of the melodramatic material, but it allows the director to re-articulate the classical/anthropological relationship between kinship and tragedy.

Ghatak’s work is modernist in the sense that it offers an aesthetic of renewal of conventions, including classical, folk, and modern conventions. Second, it is political not only by being responsive to political reality but by working on a convergence of creative language and the language of critique. Third, it works with a ‘fighting conception of the modern’—to rephrase Bertolt Brecht’s words to Walter Benjamin—so that it does not appear only as a symptom of a specific form of capitalism, but promises to reinvent itself in relation to the connected flow of human destinies that capitalism fosters. The power of this reinvention stems not only from adjustment to the unfolding economic dynamics but from acts of resistance. Finally, the modernism in question is of necessity ‘untimely’. It has to be out of step with chronology, an anomaly, for instance, with regard to the ‘modernization’ and ‘development’ adopted as a religion in the Global South. It is a critique of modernity itself for that reason. In this case, the critique should also be seen in relation to the process of decolonization, in relation to what one of the finest Indian philosophers of the last century, K. C. Bhattacharya, called ‘self-rule in ideas’. The modernism in question was part accomplishment and part promise in Ghatak. Jurgen Habermas famously called the project of modernity an unfinished one. Artists like Ghatak help us look beyond the historicist implications of that argument through the lens of an unfinished project of modernism—emerging from outside the West, assimilating the living force of European modernism, ‘supplementing’ the latter by decentring it, repurposing it, while taking it forward.

All images are frame grabs from DVDs.