It is hard to chalk out an exhaustive curve with regard to self-reflective application of colour in Bengali films.[1] Then again, Cinema Studies itself, amongst its multiple inadequacies, have been—often—limited to narrative and author studies. This literary slant, which has been thoroughly debunked in the last few decades through systematic research, dominates Bengali cinema histories in general.[2] I shall not, however, present any overview of cinema produced from (West) Bengal;[3] rather, I shall consider certain films and the uses of colour—which was a late entrant into Bengali popular cinema. As a matter of fact, due to multiple industrial, economic, and technical reasons, it was not until the 1980s that, full-fledged colour films became commonplace.[4] Yet, in as early as 1962, Bengal’s celebrated writer-director Satyajit Ray experimented with colour in his contemplative film Kanchenjunga. By this time Ray’s magnum opus—Pather Panchali (1955)—had already produced a visuality which was heavily drawing from novelist descriptions.[5] Truly, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s primary text involved exhaustive imageries of the village landscape—the foliage, its dark green shadows, anonymous flowers, free-flowing water bodies, and so on. One may contend that Pather Panchali produced a specific cinematic landscape, or a terrain comprising ‘saluk and sapla’, which generated the ‘sashya-shyamala roop’ (lush and fertile impression) of Bengal.[6] Such visual treatment may also be traced back to other influences—to training at Kala Bhavana for instance, and specifically to Benode Behari Mukherjee’s style, as elaborated in Ray’s timeless documentary Inner Eye (1972).

Take 1

In Kanchenjunga, moreover, the landscape that is produced is not merely a generic visualscape; rather, it attains autonomy and becomes an integral aspect of the narrative. The film became a yardstick of uses of colour in cinema, as cinematographer Subrata Mitra’s wellknown greyscale was transformed into natural tones, and to a colour palette which explored hues such as Ochre, Siena, Umber, Scarlet, etc. Moreover, the landscape in the mist was as much a visual exploration, as it was a narrative hinge point. For instance, immediately after Anima’s affair is uncovered, her child (seated on a horseback) calls her mother. As the child moves out of frame, mist glides in. The long shot of an enormous tree in the foreground is comparable to Abanindranath Tagore’s painting Flag (1918–19). In fact, it is clear that Ray and Mitra (as in the case of Devi [1960]) pay their homage to Abanindranath, and the pioneering ‘wash technique’ as they suture a series of images, which invoke Abanindranath’s landscape paintings of Darjeeling. About Abanindranath, R. Siva Kumar suggested that his ‘paintings of the Darjeeling series are about the world viewed in twilight […]’.[7]

The first image of Coolie Girls, in this sequence, is tailed by a shot of a mountain obscured by the mist. This shot is similar to Abanindranath’s Camel Back Hill (1916); furthermore, it is trailed by shots of huts hidden in fog, which remind Abanindranath’s The Slum (1919). Likewise, the next shot (a pan), revealing tall trees, is comparable to Towards the Valley (1919–20). Besides, as the sequence continues, one recalls Abanindranath’s Rider and Horse (in which the rider wears a red coat) (1924), as well as The Coolie Girl (1924). Later, as Manisha’s predicaments grow, fog is keyed into the scene, cogently. Such an intersection between characters and landscape lingers, and eventually ends with the melancholic Rabindra Sangeet, ‘E parobashe robe ke’. In reality, it is legendary how Subrata Mitra shot this film at dawn and dusk; thereby, encompassing the morning light, along with the slanted afternoon light, which was veiled by the mist. Apparently, Mitra awaited the mist, and thereafter, balanced it out with the skylight. Perhaps, it was a gamble of sorts, when Mitra infused mist ‘with smoke from burning leaves to create fog when a real fog was not available’,[8] and thereafter, desaturated the colour tones in scenes which were shot without the mist. Briefly, the light quality, and the colour tones—in Bengal’s ‘first’ colour film—were so discreet that only a methodical reading of visual cultures can explain the imageries Ray and Mitra strove to recreate and realize.

Take 2

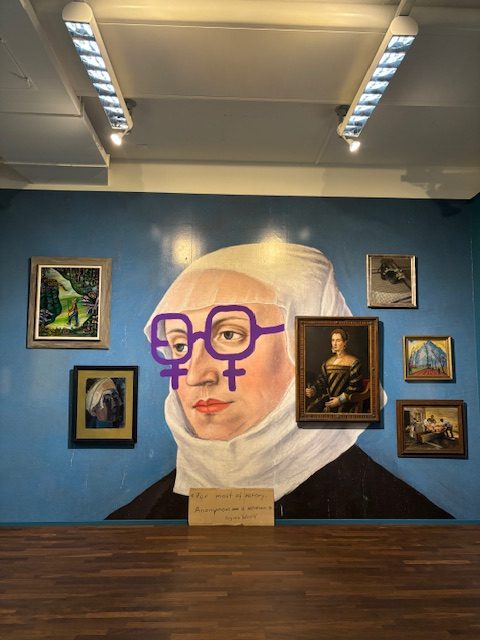

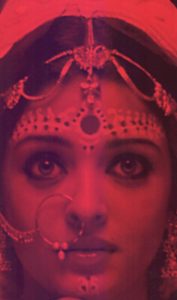

More recently, Rituparno Ghosh’s momentous film Chokher Bali (2003) explored the colour red in a poised manner. Ghosh’s success via Chokher Bali is worth deliberating considering that during the 1980s and ’90s Bengali middle-class cinema experienced a hiatus because of the changes within the industry (dwindling single theatres, and the mounting popularity of TV dramas, for example), and technological shifts (evolution of video cultures, for instance), alongside, due to the manner in which the careers of established directors and stars have shuddered, and investments rapidly waned. Ghosh thus, reinvented Bengali middle class cinema through the creation of effective stories set in evocative interiors, which refigured as emotional topographies; just as, objects appeared to attain specific narrative function.[9] Sangita Gopal suggests that, ‘[t]he film re-inflects Tagore’s themes of gender, desire, and the colonial modernity to project a vision of Kolkata’s past […]’.[10] Gopal also discusses how the technological skill of the film (and the casting of Bollywood star Aishwarya Rai) underlines an industrial shift.

Indeed, as elaborated by Ghosh’s long-time associate and cinematographer Avik Mukhopadhyay (during a personal conversation in June 2013):

With Chokher Bali the scope became bigger. Also, the set design was done carefully. We used copies of Rembrandt’s paintings in the set. I referred to the Dutch painter [Rembrandt] and recreated his dark palette and the uses of sharp source lights. By deploying the bleach by-pass technique, and by retaining the silver on the celluloid prints, we produced an intensity that commented on the darkness of the plot.

More recently, in another interview,[11] Mukhopadhyay mentions how they used red—since, besides being marked as a Passion Play, the film was set in revolutionary times. ‘Red’, therefore, indicated both desire and blood. Briefly, the intensity of Rabindranath Tagore’s novel was transferred onto the visual plane through the unique set design (and costume) of the film, and by means of the usages of multiple shades of red—as evident through the paintings/prints, flowers, the red velvet blouse, red shawl, vermillion, red benarasi, love marks, even towels (gamchha)—and, all the elements which carefully craft a world of inscrutable longing and yearning.

With the shift from celluloid’s image sensitivity to digital aesthetics, Tasher Desh (2013) made by the maverick director (and rock star) Q aka Qaushiq Mukherjee, was infamously described as ‘Tagore on acid trip’. The film reinvented Rabindranath Tagore’s classic play about a trapped prince, his sojourns, and possible revolution, into a contemporary tale about confusion, wants, utopian dreams and dystopic turns. According to Q:[12]

Tagore was a pure romantic, and I have tried to place his sensibilities in the confusion of our time. […] The look, inspired heavily by Japanese forms, from kabuki to manga, had to be basic. There are no visual effects used, apart from layering two or three visuals together, to find an image that allows all the realities to exist together, form a relationship. […] The idea was minimalist. Within that apparent reality, we would try to find the sublime. The magical.

In a curious and engaging manner thus, Ghosh and Q seem to reframe two disparate influences—those of the classical and the Renaissance; and, in the case of Q, that of contemporary popular cultures and Asian films. The graphic design, the straight lines, application of solid colours (red, black, white), as well as text and forceful sound design in Tasher Desh provoke new technological, industrial and aesthetic possibilities, and hint at renewed conversations with world cinema.

Endnotes

[1] On colour and aesthetics see Vacche, Angela and Brian Price, Color: The Film Reader, New York/London: Routledge, 2006.

[2] Also see Hayward, Susan, Cinema Studies, The Key Concepts, New York/London: Routledge, 2000.

[3] See Mukherjee, Madhuja and Kaustav Bakshi, ‘A brief introduction to popular cinema in Bengal: genre, stardom, public cultures’, South Asian History and Culture, 8.2 (2017): pp. 113–121.

[4] On colour and popular cinema see Bhattacharya, Spandan, ‘The Action heroes of Bengali Cinema: industrial, technological and aesthetic determinants of popular film culture, 1980s–1990s’, South Asian History and Culture, 8. 2 (2017): pp. 205–230.

[5] See Biswas, Moinak, ‘Early Films: The Novel and other Horizons’, in Moinak Biswas (ed.), Apu and After, Re-visiting Ray’s Cinema, London/New York/Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2005.

[6] See Mukherjee, Madhuja, ‘The Story of Arri: Imagined Landscapes, Emergent Technologies and Bengali Cinema’, Journal of the Moving Image 10 (December 2011): pp. 61–80.

[7] In Kumar, R. Siva, Paintings of Abanindranath Tagore, Kolkata: Pratikshan in association with Reliance Industries Ltd., 2013.

[8] See Mitra, Subrata, ‘Cinematography: A Personal Story’, Chitrabhash, [Cinematography and Cinematographers Special Number], 41.1–4; & 42.1, January 2006–March 2007.

[9] See Mukherjee, Madhuja, ‘En-gendering the detective: Of love, longing and feminine follies’, in Sangeeta Datta, Kaustav Bakshi and Rohit K. Dasgupta ed. Rituparno Ghosh: Cinema, Gender, Art, Routledge: New Delhi/London/New York (2016): pp. 139–152.

[10] In Gopal, Sangita, Conjugations: Marriage and Form in New Bollywood Cinema, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

[11] See https://scroll.in/reel/875920/avik-mukhopadhyay-on-shooting-october-visuals-should-communicate-feelings-rather-than-inform

[12] In https://moifightclub.com/2013/08/12/why-q-went-for-tagore-on-an-acid-trip-and-made-tasher-desh/