Visiting the Kochi-Muziris Biennale and the India Art Fair 2019, I noticed a growing interest in using handmade paper as an artistic means of expression among the exhibiting Indian artists. Here I’m not talking about artists buying handmade paper to draw and paint on, but artists who use the pulp, their own produced paper or manipulate pulp and paper in untraditional ways as an artistic statement. Since 2000, I have returned to India each year, focusing on and following the development of its contemporary art scene as well as tried to locate the remnants of the old papermaking tradition in India during extensive travels.

In an attempt to get an insight into the development of handmade paper as an artistic means of expression in India, a questionnaire was sent with to the following artists: Anupam Chakraborty, Jenny Pintu, Kulu Ojha, Neeta Premchand, Radha Panday, Ravikumar Kashi, Shantamani Muddaiah and Sudipta Das.

The following is answers by the questioned artists to thirteen questions:

1: Where and from whom did you learn to make paper?

When I compare the answers to question 1 the majority of the questioned artists have learned papermaking abroad: three from Jacki Parry at Glasgow School of Art, an Australian born artist, printmaker, papermaker, former lecturer at the Glasgow School of Art and a founding member of the Glasgow Print Studio and the Paper Workshop, two in Korea by Chang Son and Seong Woo and also Puli Paper Mill in Taiwan, one at the Paper Institute in Kochi, Japan, from Hamada San, and one in the USA by Catherine Nash and Timothy Barrett. One is self-taught and has taken a workshop at Kumarappa Handmade Paper Inst., Sanganer, Jaipur.

2: Why did you choose to work with paper – what is it you find interesting about paper?

Sudipta Das answers: “My encounter with the contextualised use of paper as a medium for my work started as a solution to the technical difficulty I was facing during my education in Santiniketan. As I started working with memories, personal histories and the layered presence of history in our identity, I was collecting historical evidence and other documents that have carried history through photography. It is from this desire to use those photographic images that I started working with paper. Soon I found that paper is one of the best mediums for my expression as its fragility and its ability to absorb tints of colours can be contextualised with the histories of fragmentation and the layers of memory that I worked with. It is from this aspect that paper becomes an important way for me to express and contextualise my personal histories of migration and the anxieties of being an immigrant.”

Anupam Chakraborty, who has chosen to place paper in the centre of his artistic praxis for twenty years cannot think of any other medium that can be equally fascinating. He states: “only those who have made paper themselves can get the experience of the versatility of papermaking.” Ravikumar Kashi points out the tactile quality, the malleability and organic nature with a long and ancient history, connected to knowledge/books. He finds it a challenge to lift handmade paper out of its stigma as belonging to craft. All the questioned artists find that pulp and paper contain tactility, texture-ality, fragility, two and the three dimensional possibilities and that the more you experiment with it the more doors will open for manipulation.

3: Do you consider yourself a hand papermaker or a paper artist, and do you feel there is a difference?

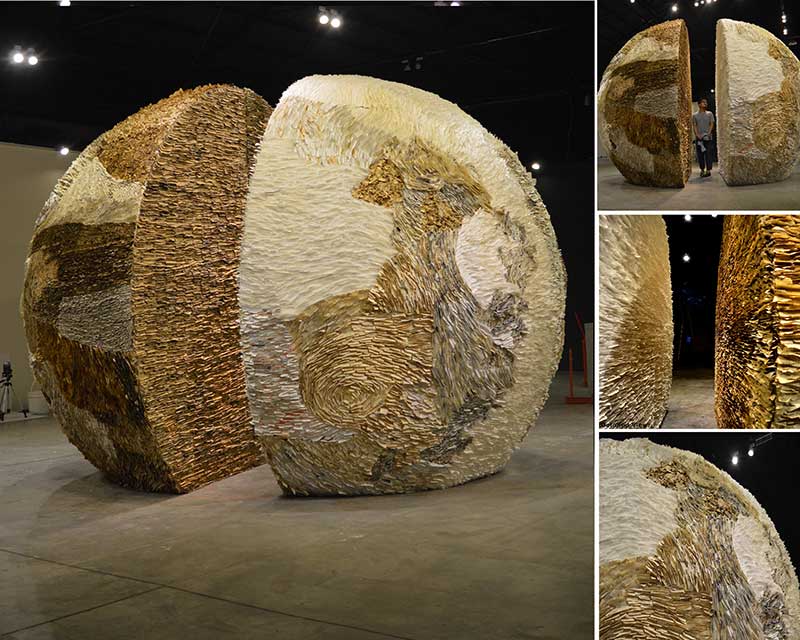

There is a widespread agreement among the interviewed artists that there is a difference between a hand papermaker and a paper artist. None of them consider themselves hand papermakers. Radha states: “hand papermakers work with qualities of the sheet that make it suitable for specific works.” Jenny considers herself a paper artist, and that the difference is in vision, interpretation and output; she says that one has to understand the material. Ravikumar considers himself as a paper artist, but he does not want to be labelled as one, as he also uses other materials. He says that a hand papermaker makes paper for its own sake. Anupam considers himself a paper artist and that refers to a creative individual, involved with the handmade paper as a means of artistic expression. Kulu says that technically he might be considered a paper artist; his actions are solutions to a number of environmental issues. Shantamani is a sculptor and installation artist, who explores fibres and pulp for architectural and sculptural forms, and she states the same as Kulu that her actions are solutions to a number of environmental issues. Sudipta will rather call herself a visual artist, but do not oppose anyone calling her paper artist, as she primarily works with paper. She writes that categorisation just on the basis of mediums is shallow and constricting without the understanding of how paper or papermaking becomes a medium of expression.

Jenny is right that the more one knows one’s material the choice of artistic output grows and becomes richer. It means a lot to commit oneself to work professionally with paper and it will, if you give in to this medium, absorb you profoundly as one will discover that it contains everything and can be everything. As Kulu says: “the language of paper surpasses the language of man.”

Concerning the categorization: society loves categorizations to get things under control. The importance here is that an artist is proud of her or his professional choice. I find a slight hesitation in the answers among the questioned artists towards being labelled and I think it is due to the ingrained Indian perception of craft versus art issue, which we will touch upon in the following. Neeta has an interesting remark: during her studies, she wanted to know the difference between how the paper was looked upon in India and Japan. In Japan, it is an art to make paper and there is respect for the craft and the craftsman. She finds that there is a lack of respect for paper in India.

- Do you teach others papermaking?

All the inquired artists have given paper workshops in one way or another apart from Kulu, who is “trending” people to use paper as their primary subject for art. Jenny teaches only design interns and has given bookbinding workshops. Shantamani has guided a rural woman sustainable project through paper products and given few workshops. Sudipta teaches children now and then and organizations on invitation, Radha teaches and gives lectures in India and abroad and Neeta has given workshops in England, Switzerland, and India. Ravikumar has conducted workshops in his studio, at art schools, architectural colleges, and art museums.

Since 2005 Anupam, who has founded the Nirupama Academy of Handmade Paper in Kolkata, is offering hands-on training/ workshops to individuals, groups, students at academic institutions, government, and non-government organizations employees at his Academy and elsewhere. He states that he has taught more than a thousand individuals.

5: Have you studied the history of paper in India or abroad? If you have ever visited paper mills and paper artists in other countries, what were your impressions?

Radha: “I studied Japanese papermaking formally first with Catherine Nash at Haystack Mountain School of Craft in Maine, US for three weeks (2005). Four years after this I went to the Philippines to study with Asao Shimura for two-three weeks. I learned how to make western-style papers but using a su/geta (Japanes mould for papermaking) with banana fibres, Kozo as well as pineapple fibres. I also learned how to make shifu (Japanese paper thread), and learned about growing and using konnyaku (Japanese impregnated paper). It was huge learning to see artists in their own studios and spaces and notice how their workspace was made to fit their needs. Asao got a lot done with very simple setups and very simple machines. The next paper-related international travel was to the Friends of Dard Hunter conference in 2010 where I met Timothy Barrett, Peter Thomas, David Reina, Jim Croft, and Catherine Nash again and others. Here I decided to apply to the University of Iowa Center for the Book graduate program and started there in 2011. The following year I visited the historic mill in Capellades, Spain. It was amazing to see all the history we had been learning about in school come to life. The year after that I went for the IAPMA (The International Association of Hand Papermakers and Paper Artists) conference in Fabriano, Italy, another eye-opening experience to see historical examples of watermarking technology and tools; as well as meeting others in the field and hear about their work in paper. As for books along the way before I went to Iowa—I read: A Papermakers Companion by Helen Heibert, The Complete Book of Papermaking by Josep Asunción, Off the Deckle Edge by Neeta Premchand.”

Ravikumar says in one of his answers: “People find it (making paper) interesting, but not many continue the exploration.”

Anupam has after his stay with Jacki Parri for half a year at Glasgow School of Art in Scotland, where he got an insight in Western and Eastern papermaking techniques, mostly done research via books and articles. He has visited Dieu Donne Paper and Carriage House Paper in NY, Two American well-known places in the paper world with a very fine set up.

Jenny has interned with Helen Hiebert in Portland, Oregon and met with many US-based paper artists. She has visited Dieu Donne, NY, visited one IAPMA exhibition and done three-four workshops in bookbinding in the US. Apart from that, she has visited paper mills in Pune, India, a Kagzi in Sanganer and Pondicherry. Jenny writes that she was impressed with many of the artists’ work in the West and she thinks Indian artists should be more exposed to the possibilities of the material.

Kulu has never studied the handmade paper and Shantamani, Ravikumar and Sudipta has mainly searched in India and in the East. Sudipta has received a Greenshield award and is documenting various centres of papermaking such as Jungshi handmade paper factory in Thimpu, banana fibre paper, Indian manufacturers in Assam and Lokta manufacturers in Katmandu. Shanthamani has visited Khadi Gramodyoga in South India, but she is still depending on paper produced in Europe. Ravikumar has met other artists working with paper during a Hanji show in Chennai. He has visited papermaking units in Bangalore, Pondicherry, Ahmedabad, Sikkim, Jaipur, and Santiniketan in India and in Mexico, South Korea, Glasgow and Nepal. He finds the Jang Ji Bang studio, Seoul, South Korea, very professional and thorough in their methodology.

Neeta has done thorough historical research abroad as mentioned before including the Silk Road, Xian, and Samarkhand, but also in India. In the 1990s she became interested in the study of paper used for old manuscripts and discovered that from the 1980s to 1990s most of the papermaking units she had seen and photographed had been destroyed, but there was a lot of paper on the market. The last mill she visited was Daulatabad, where they were famous for making thin paper in the 17th century. When she visited the mill was about to close down and spontaneously she bought it. She revived it and opened The Bombay Paperie.

6: Do you use mainly local plants/fibres in your paper production or do you import fibres from abroad?

Anupam only uses indigenous plants that grow in West Bengal and in other parts of India. Shantamani uses recycled 100% cotton rag pulp from Tirupur textile industry and states that banana fibre and jute fibre are easily available in the southern part of India. Sudipta has made paper from banana fibre and waste material. She has bought Hanji paper from South Korea – it depends on the need and the demand of the work she is making. Jenny and Ravikumar use only Indian fibres. Radha imports fibres and is looking for a good quality hemp in India. Kulu uses a readymade paperboard for his cuttings. Neeta uses her own paper from Daulatabad and old paper.

I sense a lack of broader investigation into what is possible with different plants and their bio based capacities. India has such a huge potential–there is a lot to be done!

7: What do you know about the Kagzi tradition in India, and does it inform your paper making practice?

Most artists express that the Kagzi tradition as such has not and doesn’t enlighten their paper practice.

Anupam, Neeta, and Radha have studied the history of paper in India and researched it on their own. Radha has written articles about it and is currently working on a deeper research project, which is going towards a book. She also teaches workshops on the subject. Neeta wrote about Kagzis in her book Off the Deckle Edge as mentioned before.

Sudipta states: “for me, the Kagzi tradition in India speaks not only about traditional papermaking practice but also about multi-culturalism and Indo-Islamic history.” She feels that the Kagzi tradition can show us pathways into making paper that is ecologically more sustainable.

I agree. Today one can find a lot of historical writings about India and paper history and there is inspiration to be found in these writings. Following the UN’s seventeen sustainable development goals in order to transform our world, paper and its history can open up knowledge and show one of the ways to go.

8: How is hand papermaking received in India today?

Here, again, the questioned artists seem to agree that there is a very slow-growing interest. Paper is seen as eco-friendly, but there is a lack of awareness, lack of visibility, creative intervention and lack of marketing strategy. Indian handmade paper industry does not have a systematic and planned marketing for its promotion on a wider spectrum according to Anupam. “You do not see the handmade paper in the market and even in art colleges you do not see much of handmade paper and in the publication and design area, we see very few efforts in adopting handmade paper”, Shantamani says. Jenny names it a niche market, but a growing one in the bottom of the list of materials compared to other handcrafts, due to lack of knowledge and demand. Sudipta says that through the consciousness and the practice of many contemporary artists it is receiving more attention than before.

The conclusion as far as I see is: that paper eventually will reclaim its position. Cellulose is beginning to win territory as research and experiments are taking place at universities all around the world. India should follow up on this at their universities.

9: Why do you think papermaking and the scribal arts in India have been less able to rise from their roots than the textile tradition?

Sudipta writes that “earlier we have not understood and paid attention to the amazing traditional skills present around us, which has led to stagnation to the practices. Today through research artistic approach scientific experiments and more global awareness will make the former practices dynamic again.”

Jenny “finds that textile was far more evolved in India from very early on and that weaving was a developed craft all over the regions. Paper was from the beginning for the limited purpose for art with royal patronage.”

Shantamani agrees with Jenny concerning textile and that “there are very few good hand papermaking units producing good paper. India is a developing country that thrives to acquire what is in the first-world market other than looking inward in terms of developing a sustainable product within its available practices. A lot of indigenous knowledge systems are surprisingly still alive in India and there is a greater opportunity to develop them further.”

Anupam states: “following areas can be considered for negligible growth in hand papermaking and scribal art from their roots compared to textile tradition: (a) lack of professional skills among implementing agencies, (b) poor quality measures, (c) inadequate research and development programmes, d)absence of aggressive marketing strategies, and(e) lack of involvement of artists and designers in the R&D (Research & Development) and production team.”

Ravikumar suspects that “it is because of government polices and mentions Weavers Service Centre and Pupul Jaykar, who was instrumental in the revival of textiles. No such effort has been made for paper.”

Radha mentions: “at the time of independence, KVIC did the wrong thing by introducing auto-vats and training the average person to make paper and that this was the final blow to the Kagzi tradition.” She also mentions lack of government support and interest. In Neeta’s experience, “the Khadi commission did the biggest disservice to the papercraft by showing a total lack of interest in the quality and never made any great effort to sell the paper or pay the papermakers. She also mentions that the quality of cotton available in India has poor quality. With most of the waste from GM cotton, the yarn is too loose and knots when made into pulp. This leaves holes in the paper when it is produced thin.”

The conclusion is that nobody really supports the revival of the ancient craft of papermaking.

Today, in 2019, I have the hope that artists will revive this craft and art, which has been the case since 1950 in the West and by their example push KVIC, etc. to see the sustainable and bio-based quality of paper as a new way to go.

10: Do you think the Khadi and Village Industries Commission change its approach as it sees the growing market for exported paper?

Shantamani writes, “the approach should aim at innovation within the field instead of still training basic industrial skills and nothing else.” Ravikumar has given a proposal to the Khadi commission to do an intervention project, but without response. “Paper made in the Khadi papermaking unit are unimaginative, he states.” Jenny finds that “KVIC does not understand what needs to be done for handmade paper.” Sudipta writes that KVIC should change their approach due to the growing market of exported paper: “It should not only encourage the traditional process of papermaking but also inspire them to make a viable alternative to chemically treated paper through collaboration with artists and researchers. It could be India’s contribution to the solution of ecological distress by factory-made, chemically treated paper.” Anupam writes: “Some major positive changes have been noticed in this regard since last few years. It has been observed that KVIC is presently grappling with problems on the supply side, and not on the demand side. It is one of the reasons that KVIC has been concentrating on its production facilities across the country through the help of all its supply chain agencies. KVIC, which falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of MSME, is also thought of providing incentives and shops for startups in the MSME segment. KVIC also assists the export of khadi and village industry products through Export Incentive Scheme. Besides these, KVIC also supports khadi and village industry institutions as well as REGP units and state boards for participation in international trade fairs abroad. The fairs not only provide an opportunity to find new buyers but also expose the participating units to the quality, packaging, and standard of similar products from different countries. The knowledge enables them to suitably reorient the production and process to access foreign markets as well as prepare them to compete with the foreign products coming to local markets in India.”(Note: This information Anupam has obtained from MSME & KVIC websites and from the research papers related to this area available on Google—the info is from 1990!)

These different answers tell me that KVIC is not doing enough in relation to the UN’s seventeen World Goals: In 2015, world leaders agreed to 17 goals for a better world by 2030. These goals have the power to end poverty, fight inequality and address the urgency of climate change. Guided by the goals, it is now up to all of us—governments, businesses, civil society, and the general public—to work together to build a better future for everyone. Here KVIC should direct paper production towards the innate possibility of handmade paper production: sustainability by setting up a collaborative workshop with artists and designers all over India.

11: Do you think KVIC could spearhead the revival of more traditional paper production for use by conservators and artists?

The artists’ attitude to this question is not reflecting a lot of expectations, but a tiny hope. Anupam writes: “They could if they can transfer their weakness into strength and Shantamani: Awareness and market opportunities will make a huge difference.” “The revival already has started through the hands of artists who are using handmade paper more and more, making it themselves or searching for better qualities in India or abroad, and also through curators, galleries and researchers, who have a growing interest in the old techniques. It is a slow process, but I think eventually India will get there in twenty-thirty years acknowledging its wealth existing in the production of quality products and involving qualified engaging people!”, Sudipta says

12: How do you envision the development of handmade paper and paper art in India’s future?

Shantamani states: “There is a greater possibility to develop the handmade paper into a sustainable system in India. We have an example of providing twenty women a decent salary in a rural area to sustain their families. If this project is getting attached to the microfinance support system, it can revolutionize women’s economic independence. In 2004, there were no handmade paper studios in Bangalore. But today we have three artists working with the basic amenities. Things will surely change in the coming days.” Sudipta believes that handmade paper will become an alternative to the environmentally harmful chemical treated paper. It needs to be recognized by the administrative machinery in India to make it happen.

Jenny and Anupam state that paper has to be introduced in the academic curriculum in government and private schools, art and design schools. Ravikumar sees a growing interest in artist communities. He also states that the influence slowly has come from abroad—e.g. the students, who studied with Jacki Parri like Anupam, Ravikumar, and Shantamani. Radha states that she hopes people will be proud of their heritage.

Anupam mentions the Indian Bengali sculptor and printmaker Somnath Hore (1921–2006) as one of the first Indian artists who used handmade paper as an artistic means of expression. Hore is considered a major pioneer of modern art in India. He experimented with different printmaking techniques and materials, culminating with his abstract paper pulp series ‘Wounds’, produced in 1970.

An Indian artist I would have liked to include in this project is Priya Ravish Mehra (1961–2018) who studied weaving and design at Santiniketan. Priya had what I would call a holistic view on textile; the plant, which becomes thread and is woven into cloth; a cloth that again can be transformed into paper pulp and get a new life as paper pulp. In her later work, she fused paper pulp with cloth and looked upon this as a healing process. This concept has been part of my practice for the past forty years and I’m very sad that I never got to meet Priya. She knew one of my Japanese teachersYosiko Wada who is based in San Francisco. With Yosiko, Priya made a workshop, ‘Bearing Witness’, in Delhi in March 2015.

Another artist who is worth mentioning in this context is Zarina Hashmi who was born in 1937 in India. Paper is her passion and central to her practice as a surface to print on and as a material with its own properties in history allied also with literary tradition. In the 1980s, she literalized this interest by casting three-dimensional works with paper pulp, creating forms that would become cast bronze sculptures.

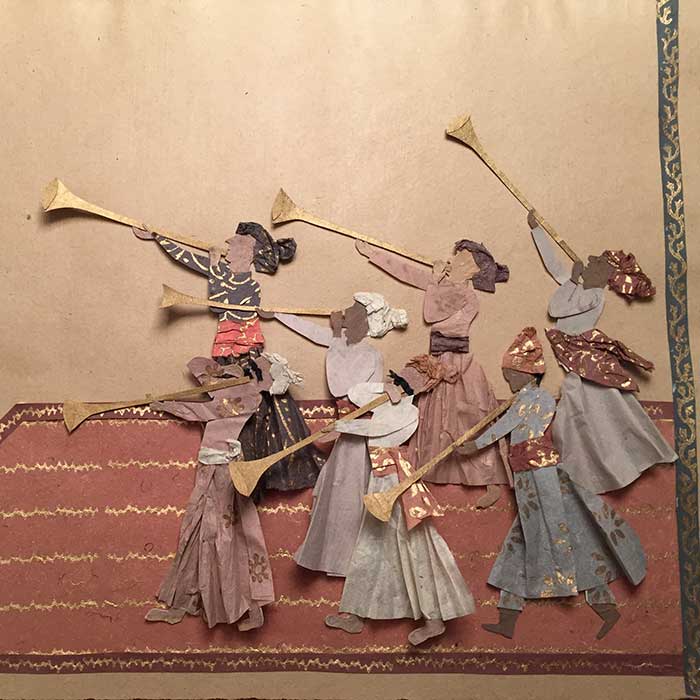

Further, the young artist Anindita Bhattachary engages with tradition in a dialogue with the contemporary world, claiming India’s heritage in her beautiful hand-cut jalis in wasli paper, painted with gouache and her own colours from natural dyes, coffee stains, and miniature paintings. (Wasli paper is created by gluing together several layers of handmade paper with archival glue, polishing and smoothing the surface by hand to prepare the paper for miniature painting.)

Anupam says: “more artists, designers, papermakers and creative entrepreneurs must take initiative to set up professional papermaking studios at different parts of the country. Besides these, a body of dedicated paper artists must introduce interactive sessions through hands-on training, slide presentations, seminars and exhibitions throughout the year to make this medium a viable one. Being a dedicated papermaking unit, Nirupama Academy of Handmade Paper conducts papermaking workshops, provides papermaking kits to academic institutes and individuals and also involved in doing collaborative projects with artists and designers, government and non-government organisations throughout the year. Papers produced at Nirupama Academy have been used by many artists, designers and private organisations in India and abroad. K.G. Subramanyan, Linda Benglis, Amar Kanwar, Priya Ravish Mehra, Mithu Sen, Yardena Kurulkar, Natalie Vassil, Marinos Vlessas & Maria Malakou, Thinley Rhodes, Maku Textiles Pvt. Ltd., Philip Qian, Jeannie McArthur Koga, Hoang Tien Quyet, Anne Vilsboell and many more are in our client list. By experiencing the increasing demand for our paper among artists, designers and in corporate houses, I am quite optimistic that quality handmade paper and paper art will play a formidable role in India’s future.”

I personally met Anupam in 2009 in his studio in Kolkata and felt very happy that someone was doing something for handmade paper! I ordered paper from him and find that he ever since has come a long way pursuing his passion and in spreading knowledge. More artists will follow, but it means a lot to choose paper as medium and have good reasons to do so. It is a rewarding journey.

13: Are you in contact with the other paper makers or paper artists in India or abroad?

Radha is in touch with papermakers and paper artists in the Western part of the world having studied at Iowa University with Timothy Barrett, taken workshops, participating in paper conferences and giving lectures and she is surely one, who has decided to transfer actions in paper knowledge to a broader audience. Shanthamani is familiar with a few artists in South India, Ravikumar is in touch with Asian artists he has met at biennials and triennials, Jenny with very few, and Sudipta knows Anupam and Ravikumar. Anupam is in touch with Western and a few Indian artists. Neeta runs Bombay Paperie and I can only encourage all artists who search good quality paper to visit her shop. She sells handmade paper with four deckle edges, unlike the two of machine-made ‘handmade paper.’ She would be delighted for the paper to go to the people who know the difference.

Unfortunately, a lot of paper is on the market as ‘handmade paper’ without being so. This fact presses the market for real handmade paper. I think it is time now for Indian artists who work with paper to meet and perhaps create an association and spread the news of such an association to all art schools and design schools, to KVIC, etc., and to make yearly conferences, newsletters and exhibitions together. Indian artists might be inspired by the Western paper art associations Friends of Dard Hunter and IAPMA. A community of like-minded people will grow and a group is always stronger than one person.

I hope that this article will create awareness and make the eight selected questioned Indian artists acquainted with each other. I’m sure there must be many more following so that India can build up its own paper family.