1. The Legacy of a Grandfather

Banaras, India. 15 August 1947.

A young, 22-year-old man stood on Dashashwamedh ghat, a small bundle in his hands. At this early hour, peace prevailed in the ghat, despite the usual bathers. The morning sun reflected in the cool water of the Ganges, its sparkling gold quivering on the surface, disturbed now and then by a torso plunging in and coming out.

The young man stood on the ghat for a long time, watching this routine scene; stiff, stone-eyed. Then, with a sudden, resolute flick of the arms, he threw the bundle he was carrying into the river; he also emptied a little box of ashes. What he did was tarpan – which in Hindu practice, is a libation to the dead; but in this case, was a symbolic act of protest, also a supreme manifestation of despondence. Because he was not so much offering as relinquishing – the khadi clothes that he had spun and worn as a freedom fighter for many years; and the ashes of a beloved leader that, by a stroke of luck, he had come into possession of. Everything that he and his cohorts had stood for, fought for, had been negated by the birth of a truncated nation, a land partitioned based on religion.

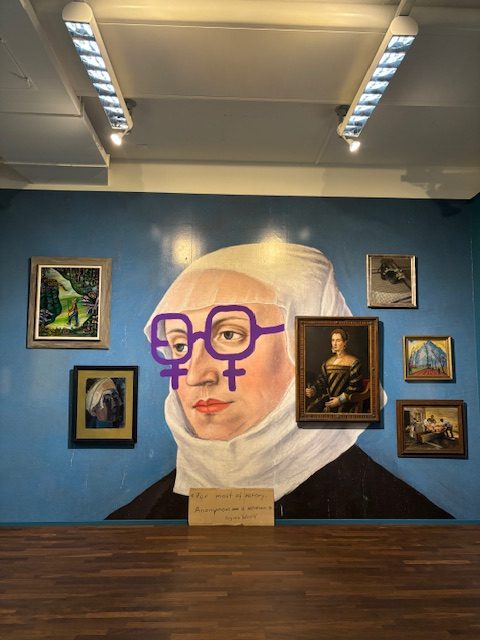

A Self-portrait of Asim Akhanda taken in self-timer in his box camera, from his photograph album, Banaras, 1947. Image credit: Asim Akhanda Archive

A Self-portrait of Asim Akhanda taken in self-timer in his box camera, from his photograph album, Banaras, 1947. Image credit: Asim Akhanda Archive

675 kilometers east, in Calcutta, a frail old man in a loincloth was fasting and spinning in silence, staving off the frenzy of communal violence in the city, one tenuous day at a time. 822 kilometers west, in Delhi, a charismatic freshly-minted Prime Minister had already ushered in freedom at midnight in eloquent prose. The 22-year-old in Banaras was oblivious to both. His short life had been completely molded by the fire of patriotism. And in that fire, he had offered his biggest sacrifice as a teenager – his dream of an art education at Santiniketan. He had come all the way from Cumilla to get admitted into Kala Bhavan, and had even been interviewed by its famed ‘Mastermoshai’, Nandalal Bose; but by then he had already become intensely involved in the Quit India Movement and its activities in Calcutta, which stood in the way of his enrolment. He felt that the call of duty was far more important than the call of a career. He could pursue art later, he told himself, but the country needed him now. That country stood torn apart in 1947. He could not accept it.

*****

68 years later, his granddaughter would memorialize this moment – emulate his tarpan in a small pond in Santiniketan: wrap herself in a white cloth splotched with the red ink her grandfather had once used, and offer it up to the water body (which became the Ganga once a small amount of Ganga-water was thrown in it), reciting the poem he had written in 1947 – khed – regretting the turn of events. It was her first performance as an MFA student in Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan. She had just woken up to the power of ‘Performance Art’, bringing to it not just what she had recently learnt from her teachers, but also the knowledge of her own body honed by years of practice in classical Odissi.

খেদ (Khēda), Performance, 25 minutes approx., 2015, Image credit: Arpita Akhanda

খেদ (Khēda), Performance, 25 minutes approx., 2015, Image credit: Arpita Akhanda

Studying in Kala Bhavan was a dream come true for her; but in doing it, she was also fulfilling what her grandfather could not.

She had been raised in Cuttack, in a succession of rented houses, each of which was an attempt at replication, or at least an approximation, of a home she had heard of but never seen, left decades ago on the other side of the border. She grew up hearing stories from her grandmother – fanning her with a hand fan as she told them in sultry ‘load-shedding’ nights – stories that started with fairies, kings and queens, but invariably gravitated to a place called Noakhali, and often to a night of riot. She was brought up in a household where she could sense her grandfather desirous of preserving East Bengal, and her father Bangla, in the state of Orissa. Most importantly of all, she inherited two gems of material memory that meticulously documented her family history – her grandfather’s photo-albums and diaries. While she always found them interesting, it was while browsing through them again, more attentively, in preparation for that first performance in 2015 that she felt “enriched” by the knowledge she had gained about her family. The desire to visit her ancestral place was also born.

Sreekail, Cumilla, Bangladesh. 1 January 2018.

They stood in front of the college – the son and granddaughter – at the very same spot where, 72 years ago, in December 1946, he had stood for the last time in Cumilla.

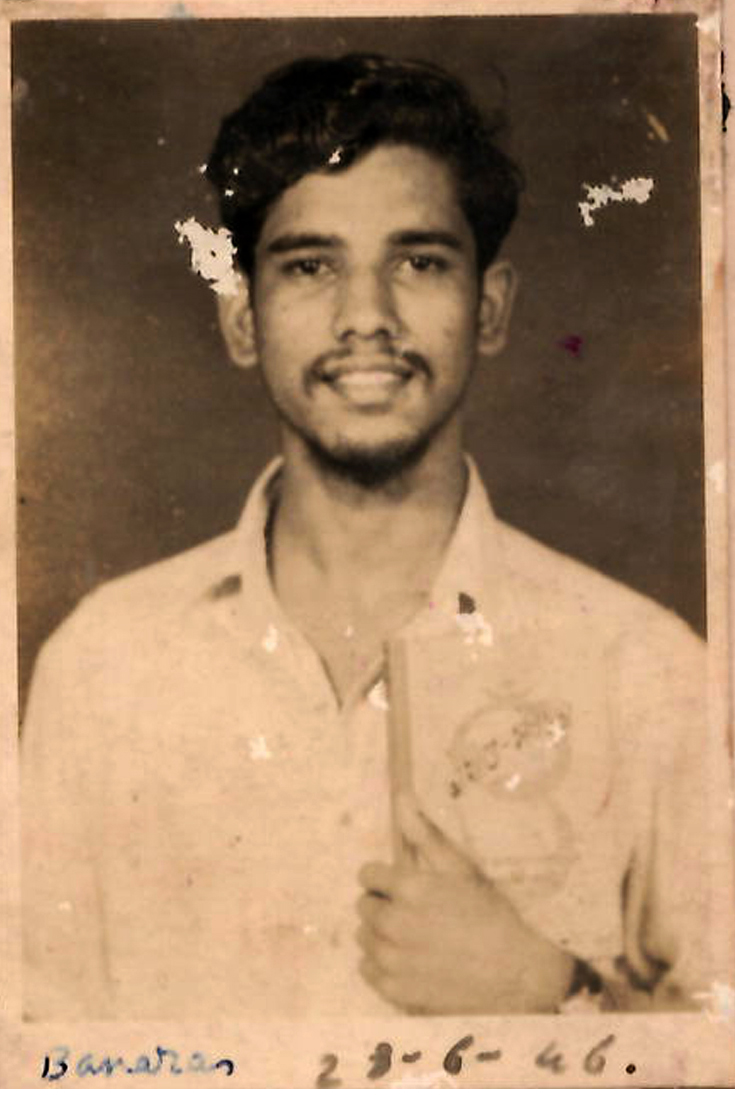

The Dissected Souvenir I, Paper Weave scanned digital print of family photographs taken during and after partition and texts collected from digital archives , Displayed at- Inside the Fiber, Curated by Soma Bhowmik, Artsacre Museum, Kolkata 2019, Image credit: Asim Akhanda

The Dissected Souvenir I, Paper Weave scanned digital print of family photographs taken during and after partition and texts collected from digital archives , Displayed at- Inside the Fiber, Curated by Soma Bhowmik, Artsacre Museum, Kolkata 2019, Image credit: Asim Akhanda

He had a premonition that it might be his last time: it was a hurried visit home from West Bengal, to come and fetch his mother to a safer place, because by then it had become clear that the communal situation in India was rapidly deteriorating and it could be headed towards a division. He had a camera with him on that visit, with which he photographed as many things of his life and living in the soil that he had been brought up, as he could – his home, family members, neighbourhood and college. These would become the basis of several treasured family albums. He would also write diaries, filling them with songs and poems and sketches, and recounting in them his erstwhile life in East Bengal (sometimes in the guise of dreams) with meticulous detail. One of them had a road map to his home in Sreekail village in Cumilla, should anyone visit it in the future. The location was not only specified with landmarks, but the history of those landmarks was also given. Long before the smartphone, he had furnished his descendants with a family photo gallery and a Google map of their ancestral home. With these as guides, his son and granddaughter found their way around in Sreekail with ease. The landmark of a temple and the accidental discovery of a neighbour led them to their original home and their present occupants. An initially diffident – but eventually long conversation and several photographs later, they returned to India with a handful of soil that became the foundation of their new home in Cuttack.

*****

It was an unforgettable day for the granddaughter. As she stood in front of the college, two moments became immanent in each other: her grandfather taking a photograph of the institution in 1946 and she visiting it in 2018. When that old photograph and her experience came together, she “realized how memory can become evidence” and how “a family archive can dissolve into a larger history”.

11. The Art of his Granddaughter

She would go back to the family archive of photo albums and explore ways of connecting it to the larger history of Partition.

Weaving

Weaving seemed to her “a befitting language” to do that – the warp and weft signifying two narratives, which created a third as they came together in the weave. She chose paper as a medium for the weave, because of its immense possibilities, and her first work in this category was The Dissected Souvenir Series (displayed in 2019 at Artsacre, Kolkata, as part of the show ‘Inside the Fiber’). In one of them, taken in 1946 in Banaras, her grandfather is smiling into the camera. In another, his college in Cumilla is beautifully reflected in a pond. The warp of these photos is transversed by the weft of official British telegrams of how the Partition of India would be executed, with the division of land and assets as well as the armed forces; the cryptic words of the telegram disrupted in the paper weave.

She would explore the metaphoric power of the weave further in Dak-Ghar (part of the Emami Art online Art Exhibition ‘Aroh’ in 2020), taking the title of Tagore’s famous play. Her grandfather had lived in a succession of rented houses, in each of which he took some photographs either of a family member or a room; and in every such home, letters would arrive from dear ones, the only means of communication in those times. In this work, she wove those postcards with relevant photographs for each address. Blank postcards stood for homes where no letters came.

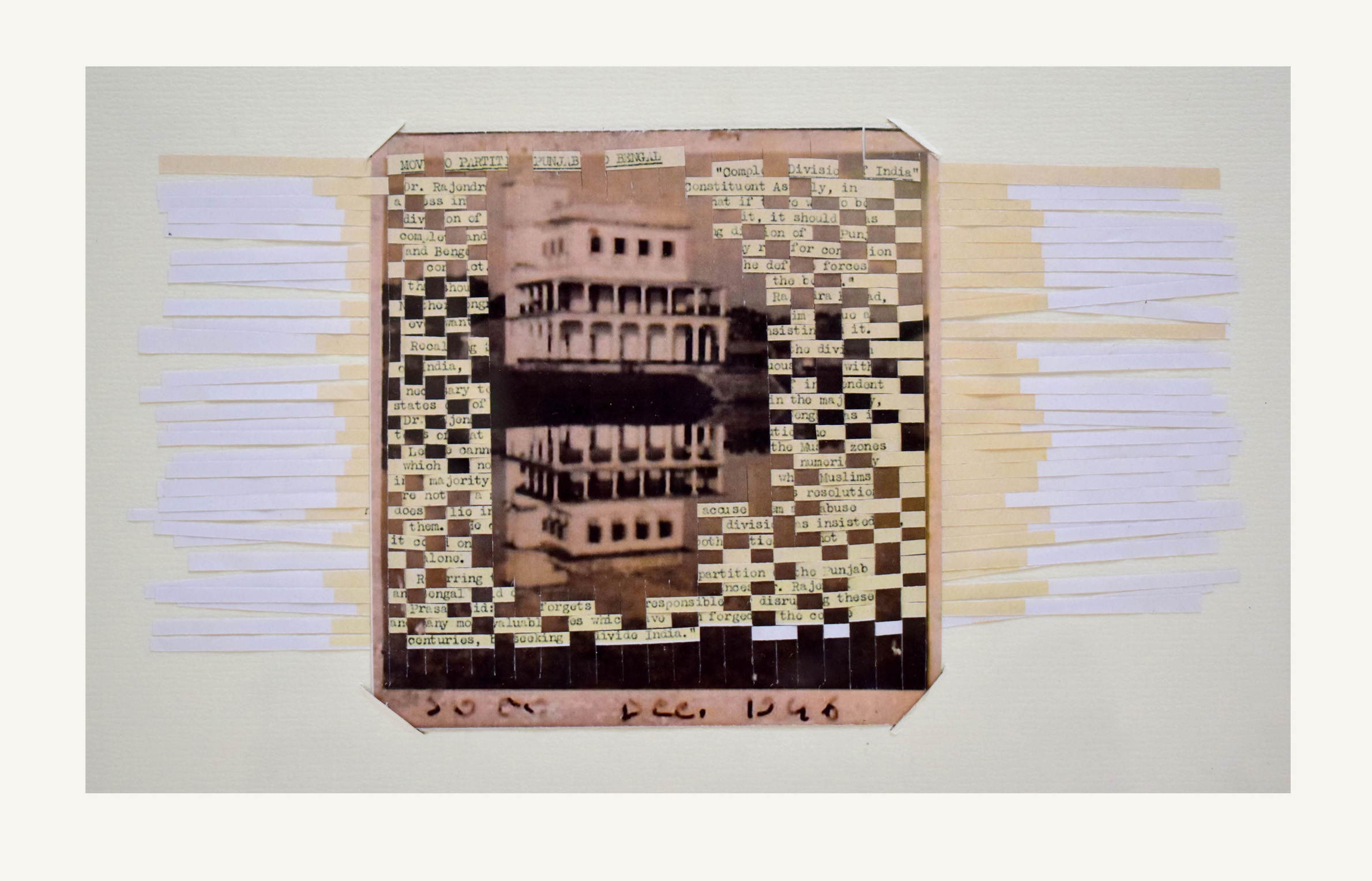

Body of Water I , Photo-performance and maps of rivers, Paper weaving on archival print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag archival paper, 16.5 X 12 inches each approx., Part of শরীর | Körper: The memory collector, Kunstrum, Aarau, Switzerland. 2021 Photographed by Nathanael Gautschi, Image credit: Arpita Akhanda

Body of Water I , Photo-performance and maps of rivers, Paper weaving on archival print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag archival paper, 16.5 X 12 inches each approx., Part of শরীর | Körper: The memory collector, Kunstrum, Aarau, Switzerland. 2021 Photographed by Nathanael Gautschi, Image credit: Arpita Akhanda

Photo and letter, map and telegram – compellingly convey the materiality of stories. But there were also stories with no visual reference – stories her grandmother had recounted of women who had crossed mighty rivers to seek shelter. In Body of Water I & II (displayed in 2021 at Kunstrum, Aarau, Switzerland, as part of ‘শরীর | Körper: The memory collector’), she remembered the stories and became the women herself; standing in for them, dressed in different avatars. There were other stories of women whose images had been preserved, but names lost. In In Memory Of (displayed at IAF 2022), their portraits reflect in mirrors with shredded maps; victims of experimental map-making in a divided land.

Performance

A Screenshot from The Living Scar, Performance video and text from the artist’s diary 04:54 minutes, 2021, Image credit: Arpita Akhanda

A Screenshot from The Living Scar, Performance video and text from the artist’s diary 04:54 minutes, 2021, Image credit: Arpita Akhanda

While her experiments with paper weave are intriguing, it is in her performances that she is most arresting. The Living Scar is a video of the tattooing of her forearms with the outline of the Radcliffe Line in both Punjab and Bengal, her arms representing the western and eastern borders of India, framed by the mainland of her body. Her body thus not only becomes the dissected land of the nation, carrying two indelible scars; but by this act, she also consigns herself to “live between these two scars”.

The video was shot in real-time, in Aarau, Switzerland, on 17 August 2021; the tattoo artist went against her practice to give her a slot at short notice, after coming to know why that day was significant. And the piercing pain of tattooing became an integral part of inscribing India’s border on her body.

360 Minutes of Requiem was a show stopper at the India Art Fair 2022 – performed for six hours over two days. Clad in white, with her long hair open, she painstakingly unwound 360 feet of barbed wire, to deconstruct notions of partition and borders (not necessarily political), the innocence of her persona juxtaposed against the violence of the act. The audience’s response to it was something she was not prepared for. They came and patiently sat with her through the performance. At the end of each day, some would leave little notes for her, some share with her their family stories of Partition, while others confide they felt a pain when the barbs pricked her during her performance. A little child was concerned about her bleeding thumbs: why did she not wear a glove, she asked her mother. The mother explained the reason and made an Instagram post about it, tagging the artist.

360 Minutes of Requiem, 3 hours, 2 days, Performed at The studio, India Art Fair Grounds, India Art Fair 2022, Image credit: Emami Art

360 Minutes of Requiem, 3 hours, 2 days, Performed at The studio, India Art Fair Grounds, India Art Fair 2022, Image credit: Emami Art

She had done a 15-minute performance with the barbed wire before at Emami Art, Kolkata, but realized the theme demanded an act of a much longer duration. The six hours of the performance at IAF wound out into 360 long minutes. Her thumbs were injured; for a month she could not use her phone as she could not swipe her thumb over the screen lock. In questioning the border, she was close to losing her identity, as any thumb impression was ruled out. This fact haunted her for a long time.

The Artist and her Oeuvre

Inspired by her grandfather’s life and her family history, Partition is thus central to the work of Arpita Akhanda. Multi-disciplinary in her practice, as we have seen – using photography and performance, video and installation – Arpita has already made a mark as an artist at a very young age, with her work being showcased at several prestigious venues both within India and abroad. She has also been the recipient of artist residencies, the latest being the Jan Van Eyck Residency in Maastricht, the Netherlands. And her latest laurel is the acquisition of her work, I Am Not a Refugee II, by Museum Kunstsammlung NRW (or K 21) in Dusseldorf for their permanent collection. She will also be featured in V-KPM – the Virtual Kolkata Partition Museum, memorializing the Bengal experience of Partition – to be launched soon.

আমি উদ্বাস্তু নই (I am Not a Refugee) II, Paper weaving with archival print on, Innova smooth cotton high white 100% cotton 315 gsm, Fourdrinier acid-free, archival museum-quality paper 63.7 x 57.4 in. (162 x 146 cm.) approx. 2023 In collection of Museum Kunstsammlung Nordrhein- Westfalen K21, Dusseldorf, Germany. Image credit: Emami Art

আমি উদ্বাস্তু নই (I am Not a Refugee) II, Paper weaving with archival print on, Innova smooth cotton high white 100% cotton 315 gsm, Fourdrinier acid-free, archival museum-quality paper 63.7 x 57.4 in. (162 x 146 cm.) approx. 2023 In collection of Museum Kunstsammlung Nordrhein- Westfalen K21, Dusseldorf, Germany. Image credit: Emami Art

In the span of only a few years, one notices a significant evolution in Arpita’s artistic trajectory — from her immediate family experience, one perceives her gradually distancing herself and seeing the bigger picture, as it were; moving/spreading out from home to the world, from the personal to the universal. From working on and being inspired by family albums to graduating to maps to etching the map/border on her body to unfolding barbed wires.

It is interesting to note that in her initial use of maps, there is a lot more specificity and locationality, as she pins down places and people in it. But the map on her body is generic; there are no locational marks in it – just the outline of the Radcliffe line on the western and eastern borders of India. She is thus encompassing the whole of Punjab and Bengal in her body, making it much bigger in scope than her previous work with maps. And with the barbed wire, she is dealing with borders and boundaries, not India-Pakistan, thus widening the scope of her work even further, and revealing a more profound understanding of the concept of partition and division. There is, therefore, a transition from the personal to the national and beyond, in her artistic engagement with Partition.

Dak-Ghar, Paper Weave, Archival print of Archival letters and photographs collected from the family archive. Displayed as part of Emami Art Open Call Online Art Exhibition – ‘Āroh’, curated by Ushmita Sahu, 24 x 32 inches approx. overall size, 2020, In Private collection, Image credit: Arpita Akhanda

Dak-Ghar, Paper Weave, Archival print of Archival letters and photographs collected from the family archive. Displayed as part of Emami Art Open Call Online Art Exhibition – ‘Āroh’, curated by Ushmita Sahu, 24 x 32 inches approx. overall size, 2020, In Private collection, Image credit: Arpita Akhanda

In the past decade and a half, there has been significant work done on the subject of Partition, its aftermath and afterlives – with a focus on geographical sites of ancestry, the border, migration and displacement, refugee colonies and inherited memories. Arpita is the youngest of the artists who have made this theme their own, to varying degrees. But what distinguishes her work is that it is entirely predicated upon ‘familial postmemory’ – i.e., the transgenerational transmission of memory of traumatic events; a concept introduced by Marianne Hirsch with respect to Holocaust survivors, but expanded in scope since to apply to other traumatic historical events.

As she says herself: “A memory I have, which I may lose tomorrow, or a memory handed down to me by my grandfather or grandmother… I want to share that memory with the world. That’s all… That’s my only motivation… My art – what I understand of it – is just not art; it is a documentation of all these experiences of my family”.

(This article is based on an extensive interview of the artist taken by the author in November 2022)

#RituparnaRoy #ArpitaAkhanda:TheMemoryCollector #takeonart #takewriting #takecurator #artcurator #artwriting #artcritics #artpublications #curatorialwriting #artcriticism #arthistories #artdiscousre #artcollaboration #artcreatives #artcommunities #arthistory #criticaldiscourse