Introduction text by Amrita Gupta Singh

Historically, the cultures and processes of print are intrinsically related to values of literacy, democratisation of learning and mass consumption. While the codification of Graphic art in India is multifarious, the focus of this article is on an interview between the eminent artists, K.G. Subramanyan and Jyoti Bhatt published in the Lalit Kala Contemporary, Volume 18. The year of publication is not mentioned in the volume, it is assumed to be done in the late 1960s and the Librarian at LKA was unable to provide the exact year! This candid interview contextualises Bhatt’s practice which is full of intriguing shifts (painting, printmaking and photography), while providing the reader a valuable range of inter-mutual ideas between two noted cultural thinkers.

Printmaking in Baroda was introduced as a specialised Post-Graduate course only in the late 1960s, though the faculty was established in 1949. Earlier, the Govt. School of Art (Calcutta), Kala Bhavana (Santiniketan) and Delhi College of Art were the nodal centres where printmaking became a specialist activity with the establishment of graphic studios/departments. Given the mechanical processes involved in printmaking and its history of being used in illustration, documentation and mass production, its repeatability in the form of multiple prints has often raised critical questions about the ‘originality’ of the print as opposed to that of a painted image. Though printmaking/graphics as a ‘fine’ art shares historical patterns with the development of older media such as painting and sculpture, the hierarchy between painting and graphics proved to be detrimental with the latter becoming a marginalised practice. This interview is a seminal art historical document that maps the history and values of graphics, its multiple mechanised/aesthetic processes, infrastructural problems and the politics of the art market. It also has parallels to the theoretical issues discussed in Walter Benjamin’s seminal text (The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936).

Being contemporaries, Subramanyan and Bhatt accord to similar ideologies and it is important to interrogate that their early painted works were inclined towards modern international trends and it is in the mid-1960s that the art language of both the artists shifted to indigenous styles. While Subramanyan continued in the medium of painting, Bhatt chose printmaking and photography as alternatives to painting and he mastered almost all its methods, though intaglio proved to be closest to his sensibility. Along with other artists, Subramanyan played a seminal role in developing the pedagogy in Baroda which aimed at democratisation of art practices, an ideology shaped by his experience in Santiniketan. Bhatt’s shift to graphics is linked to his encounter with the intaglio prints of Krishna Reddy and also his education in this medium in Italy (1961-62) and New York (1964-66). Subramanyan introduced the annual art fairs in Baroda which popularised printmaking with quotidian materials and Bhatt (though teaching in the painting department) largely moulded the way printmaking was practiced in Baroda.

Printmaking involves arduous labour, assistants and technical honing and the founding members at Baroda were drawn to its community activity, wherein caste, class and aesthetic barriers of art and craft could be dismantled via such practices. The role of the artist was to be a conscious thinker involved in sociological investigations and the artistic orientations of both Subramanyan and Bhatt were embodied in a shared historical experience of a polemic modernism in India. What is also noteworthy to read is though Bhatt advocates the mechanistic aspects of the medium, he also asserts the ‘made by the hand’ authority of the printmaker and delineates the differences between a commercial print and an artist print; this is also an indicative marker of why he chose intaglio as his main medium which “demands the touch of the artist’s hand and his presence”. Also, the “craftsmanly” aspects of graphic processes suited his sensibility which had requisite linkages to his parallel practice of photography that documented the dissipating living traditions; he incorporated various pictorial values of rural arts interspersed with art historical references and images of the urban street. An ‘interocular’ dialogue between various visual genres is witnessed in his work that is self-reflexive in nature and dissolves the binaries of the ‘high’ versus the ‘popular’, which Subramanyan also made operative through painting and public art.

The interview maps out how the socio-economic conditions in Post-Colonial India, the lack of sophisticated graphic studios outside the art schools, the expensive material costs and the politics of patronage prevented many artists to pursue this medium, only experimenting with it briefly in their careers. It has immense contemporary relevance because the possibilities and the problems of printmaking are concerns shared by many young graphic artists today. Speaking on the historical significance of art objects having both aesthetic and functional values, the conversation raises urgent questions about the capitalist exclusivity and the elitist bracketing of contemporary art. The lack of a larger informed community, ranging from the industrial manufacturer, the government, the gallery and the buyer poses serious issues of ‘choice’ for aspiring printmakers.

Bhatt elucidates that “art is an essential and not an accessory activity of a welfare state and deserves minimum priorities”. Given the political correctness of the miniscule ‘art-world’, it is rare to find interviews where two revered artists/thinkers discuss in print the politics of the market and art prices, particularly in a comparative analysis of the art markets of India and the West. If a painting can be highly priced, why not a print and if a print sells at high prices in the western market, why do Indian gallerists falter to support talented printmakers or educate the patron? Why do many printmakers shift to painting to survive? Is it necessary for a patron to be always rich; are the possibilities to create a middle-class buyer community a utopian idea? Given that a majority of artists originate from low-income and middle income groups, isn’t it an alienating experience to survive through the oscillating shifts of taste and the market, regulated exclusively by rich buyers? Subramanyan and Bhatt advocate for a middle-income buyer who is an informed art enthusiast, yet confused about the art system. This interview is a pedagogical treasure that envisions the ideal/promised democratisation of art practice, visual literacy, sustained discourse and collection, chronicling possibilities of art reform that can only evolve through libertarian strategies of making, support and dissemination.

K.G. Subramanyan: Jyoti Bhatt

Lalit Kala Contemporary, Volume 18, pg 25-28

K.G.SUBRAMANYAN: I am not too sure when printmaking started being taken seriously by modern India artists. The earliest names I remember are those of Nanda Babu, Benode Babu and Mukul Dey. Nanda Babu and Benode Babu experimented with various media-like woodcut, linocut, etching, dry point and lithograph. Mukul Dey kept mainly to etching and drypoint. In the background of Nanda Babu’s and Benode Babu’s prints one can see stone rubbings, Far-Eastern woodcut prints, traditional votive prints, and to some extent the broad black and whites of the German Expressionists. Mukul Dey’s work grew on the knowledge of the graphic work of William Rothenstein and the British etcher, Muirhead Bone. Some artists of the following generation took to printmaking in a larger way. Biswaroop Bose went to Japan to be trained in Japanese colour woodcut. Ramendranath Chakravorty, and L.M. Sen made printmaking by woodcut and linocut their forte, they are today known more by their prints than by their paintings. Of the same generation another name worth nothing is that of Yagneshwar Shukla. But to all these artists printmaking was still an accessory medium to regale themselves with; they did not choose it as some of you have done, as their main medium of expression. When did you, yourself, start thinking in terms of being a printmaker?

JYOTI BHATT: The thought did not come to me till I went to Italy in 1961 and learnt intaglio printing. My enthusiasm for the process was large enough to make me wish to join the next Atelier 17 in Paris and develop this interest further. By this time I had seen the prints of Krishna Reddy and got to know him. But the visit to Paris did not materialise. The chance came in 1964 when I went to USA on a Fullbright Grant. There I worked in Pratt Graphic Centre. The intaglio process fascinated me. It suited my craftsmansly temperament. Also the slow working out of an image through progressive proofs with its various surprises suited me, so what started as technical curiosity slowly became my main métier.

K.G.SUBRAMANYAN: Today a print maker is more of a specialist than he used to be. He has more technical choices of both tools and media; also, their latitude of use is large enough to engross and satisfy him. But do you think printmaking is a different experience from that of painting? Or in the other words, what do you think is the difference between the print and the painting?

JYOTI BHATT: There certainly are differences. Firstly, size; prints cannot look forward to being big, at least, the same size as paintings. True, people do now make prints of very large sizes. But painting sizes have also have shot up in the same measure. And large-size prints cannot be made without special technical help or large-size printing machines, which are available only in a few places, anywhere. And are almost non-existent in this country. So this is a still a valid difference. Then there is the fact that there are more technical limitations to printmaking. The printmaker does not spell these out as drawbacks. They are special advantages to him that he thrives on; their challenge makes his work specially rewarding.

K.G.SUBRAMANYAN: I can see that. Today what you can do with graphic is better understood and their range is larger. But I can think of another great difference, though, here too, it depends on what kind of printmaking and what kind of painting we are talking about. This is the fact that in most printmaking processes the image is surmised, not seen, till the penultimate-stage. The image on the block or stone or plate is not close to what a printed image is; the print is spectacularly different. This undoubtedly is an exciting feature to the printmaker this slow and secret growth and the sudden materialisation in the end. In painting, on the other hand, the image grows directly under your eye. It is this indirectness that something inhibits an impatient artist like me from using printing methods as often as I would like. But whatever it be, printmaking has certainly come of age today. No longer does the print image. I think Bill Hayter had some hand in this transformation of status in the beginning; though it has come a long way since then. He made printmaking a great adventure. He enlarged then its horizons. He made the print no less mysterious or complicated than any other work of art. Now, what are your views on the global printmaking scene today?

JYOTI BHATT: In most of the world printmaking has become a larger activity in the last few years. In certain Western countries, especially USA, the print has acquired a status comparable to that of painting; many painters of standing turn to printing for at least part of their time. And some and these are a large number, work as printmakers exclusively. The activity has received a big boost. The public is educated into appreciating the qualities of a print through exhibitions, publications, and library services. The necessary accessories and materials are available easily in art stores. Galleries have taken initiative to sell the print to the buyer of moderate means. They commission editions by the best artists. Special workshops like Tamarind and Pratt Graphic Centre enlarge and refine the activity. Print exhibitions, being handier, get circulated extensively. There are even Print Biennales in the word today. Side by side with this, the technical range has also increased. Printmakers today use a large variety of materials and processes thrown up by the industrial scene. The artist and printing specialists are able to collaborate and produce work that are strikingly novel and are able to tickle the aesthete’s palate.

K.G.SUBRAMANYAN: That is a good picture. Compared to it our situation should be found wanting in many ways. But before we come to that I would like to raise a point about the use today by printmakers of mechanical techniques in their work. Although photo-mechanical devices have been used in the printing trade for over a century the artists and printmakers resisted using them for a long time. One can see why. They probably thought that the use of complicated mechanical devices will interfere with spontaneity of their statement. They perhaps found the techniques themselves limiting and the technicians they had to work with rigid and unaccommodating. They also perhaps had a sense of status that set technical considerations beneath them. But now the situation has changed. The frontiers have blurred; the printing trade has grown greatly in dimensions with a highly diversified technology and a tremendous amplitude of function; the printed image today is ubiquitous, informing, explaining, warning, wheedling; a large section of a new urban generation has grown up amidst these even as an earlier generation grew up amidst fields and flowers. And visual communication activity brings together today a variegated panel of experts, from the designer-artist to the craftsmen-printer. So one can understand why the resistance has broken down. Now the question is, do you as a printmaker welcome the use of mechanical means?

JYOTI BHATT: Personally, I do not see why mechanical devices should not be used by an artist. If any such device helps an artist to secure his aim and makes his task easier why should he hesitate to use it? In fact all artists have used some tool or the other since the prehistoric times. Cameras, enlargers, and other mechanical devices are only more advanced types of tools. Why should he not use them if they serve his purpose? It is immaterial to a printmaker whether his block is inked by a hand roller or a mechanised roller, if it does the job as he needs it. It is true that many printmakers prefer to use simple tools they can control manually. Others keep away from mechanical devices because they are too complicated or expensive or difficult of access. Also certain printing methods, such as the intaglio printing of Krishna Reddy, demand the touch of the artist’s hand and his presence. But other kinds of prints, serigraphs, monochrome intaglios, lithographs can be done by a professional printer as adeptly as by the artist; sometimes the professional does it better and in less time. The use of the readymade image too is as valid, in my opinion, as the use of autographic images; even in traditional art we can see the use of standard images, chosen from iconographic handbooks; they are ready-mades of a kind. It may be true that the use of photographic images cuts out use of the hand and knowledge of drawing etc. that goes with it. But in the final count the hand also is a kind of tool and it is judgment that is supreme. My own prints are sometimes completely autographic, sometimes photographic, and sometimes done with the combination of techniques. I have often taken my own photographs and used images out of these in my prints; I have also taken the help of friends and colleagues in printing them.

K.G.SUBRAMANYAN: I suppose that in these days when socio-psychologists categorise the television as an extension of the eye, the radio and phonograph as of the ear, and the telecommunication network, of the nervous system, it is not difficult to visualise today’s technological devices as more complicated tools and tools as extension of the hand or the hand itself a tool-extension of the mind. The point to ensure is that there is a connecting thread running through these, which controls and is watchful. But to clarify this further I will ask you another question. Would you, after accepting all this, differentiate between artist’s print and a commercial print?

JYOTI BHATT: Yes, I would. A commercial print is different from an artist’s print because its purposes are different; the commercial print reproduces, or tries to create the illusion of an artist’s work, however close; the artist’s print is an artist’s work, his involvement in it is more; even if done by mechanical devices he follows it step to step either all by himself or with a technical. It could be that sometimes to an artist’s print, but the difference still remains.

K.G.SUBRAMANYAN: And so it may. Though I would not myself argue the point too much, nor even the respective roles of a work of an art and a poster, for instance. Many things we consider works of art today were mere functional things and I would even look forward to a day when all our things will be works of art, transient or otherwise, to a day when the functional and aesthetic activities are at least continuous in spectrum. This largely depends on the increase in fabricational expertise and the freedom that results from it. Our printing trade has enlarged considerably in depth and range in the last few years but compared to that of what are called the developed countries it is still small. Our printmaking scene too is small and not yet terribly adventurous. This is understandable; it is only in the last ten years that our artist have taken to printmaking with a sense of seriousness. But, granting that, for a country where most of the informed art-enthusiasts are people of moderate means the scene is not enlarging quickly enough. What do you think the reasons are?

JYOTI BHATT: The Indian printmaking scene has doubtless enlarged in the few years and today there are least a dozen or more full time printmakers. But the point to notice is that they are all young. There are very few senior artists giving their whole time to printmaking-or at least a large part of it (except Kanwal and Devayani Krishna, Somnath Hore and Krishna Reddy). And the young printmakers are working against great odds. The galleries, few as they are, are interested in dealing only in painting. They go by the advice of a bunch of senior painters. None of them is prepared to buy an edition of prints. Then, the workshop facilities are few. Most of our graphic workshops today are in the art schools and colleges. The few as there are outside are merely equipped. Individual printmakers especially the starters, find it hard to set up and run a workshop of their own. Materials too are hard to come by; zinc and copper plates or alcohol and spirit, being controlled commodities, are difficult to obtain. Paper and inks are manufactured in this country mainly for commercial printing; they do not always satisfy the needs of the printmaker. The manufacturers are not interested in meeting these either as they have to bend themselves double to meet the demands of the printing industry. So is it any wonder that printmaking is not picking up? Only concerted action by art organisations and artist organisations to improve the situation can help. This may include educating the public on the qualities of print; educating the manufacturers in the needs of the artist-consumer and the advantages in serving them; educating the government into recognising that art is an essential and not an accessory activity of a welfare state and deserves certain minimum priorities. Also the artist into realising the need for preserving the highest standards in printmaking. For one will have to admit with regret that a large number of prints shown in our exhibitions do not conform to international standards in technical quality.

K.G.SUBRAMANYAN: I agree that the Indian printmakers are working against great odds. In former days the printmakers were few and their needs were small and they could to some extent count on imported material. But things are different now. We have stopped imports of goods, but our manufacturers import their technology and so are limited in initiative. So we are poorer both ways. The lack of initiative runs from the industrialists down to handicraftsman. Our hand-made paper industry should certainly be able to produce suitable paper for a printmaker but they do not seem to care. They would rather produce craft or ornamental paper. But nevertheless, I would not blame the quality of prints on these. One should be able to produce things of quality even from the humblest of materials. Our old prints, paintings, folk art and craft objects prove this conclusively. Our printmakers are more often than not, too easily pleased with an accidental effect or two and are not too careful about the overall quality-nor is the Indian buyer. But now, what have you to say to the gallery-man’s complaint that the Indian printmaker prices his prints too high as compared to paintings or drawings?

JYOTI BHATT: In countries like USA, prints (generally made in an edition of 20 to 100) are sold at 10 to 5 percent of the average price of paintings. This would probably have been the case in India too if prints sold well and, so, were produced in large editions. But prints sell here rarely. The prints are not bought in this country by the middle income non-affluent buyer’s for there are hardly any such buyers. Those who buy prints in India are the same as those who buy painting, the well-to-do Indian or the foreign tourists, who by Indian standards should be considered rich. So the circumstances as help such a pricing are not there. Another reason for this is the fact that some of our printmakers sell their prints through foreign galleries abroad and are anxious to keep a party between their inland and outside prices. In any case, if a printmaker is sure about selling an edition, or selling individual prints in such a number as will recompense him for the trouble in the same measure as a painter, the price of the individual print is bound to come lower. But not till then.

K.G.SUBRAMANYAN: I should normally not have raised this question. I feel embarrassed discussing prices, especially when I see that certain works of art go for high prices and certain do not and these variations are no indication of their inherent value. But there it is; all artists live on the money they earn by selling their work. I would, however, think that the artists have to be a little considerate to the middle-class buyer, who in our country cannot even dream of possessing works of art at their present prices. But it is in this class, probably, that there is an informed and sensitive minority who can get out of works something more than the mere pride of possessing them that an artist will be able to converse, if not today, some day. I also suspect art into decorative knick-knack, dumb, pretty and eye-soothing, or dramatic and eye-shocking, whichever it may be. But then we do not have much of a choice. We live in a country of small choices.

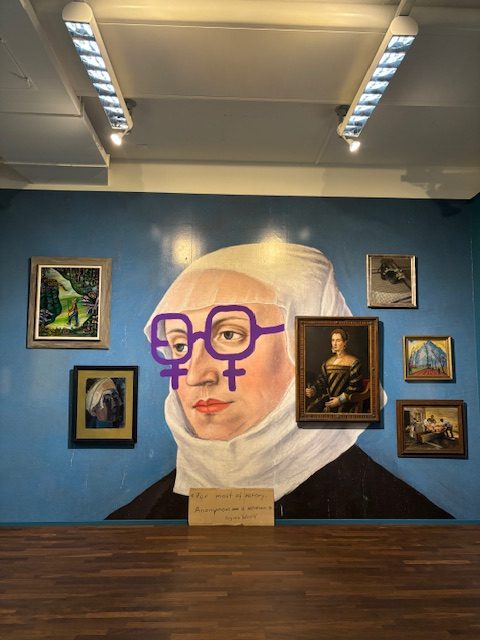

NOTE: The images are only used to illustrate the article.