Harshit Agarwal’s artificial-intelligence show ‘EXO-stential: AI Musings on the Posthuman’ is India’s first solo AI art show. This cutting edge and thought provoking show was curated by cultural producer Myna Mukherjee and ran at Emami Art, Kolkata in September (11–31). Harshit’s art begins by destabilizing the binaristic perception of humans vs technology and instead urges us to think of the human-machine as a continuum. At the onset the idea of art generated through artificial intelligence (AI) is difficult to digest. In her inaugural remarks at the show’s opening on September 11, Myna remembers the significance of September 11 as the day of the bombing of twin towers where technology was used to create destruction and instead urges that this day be remembered as one where the role of technology creates a significant dialogue with art. This reminds us that 2001 was not only the year that the twin towers were bombed, 2001 was also the year Steven Spielberg released Artificial Intelligence (21 September 2001), a posthuman take on the tale of Pinocchio—where machines are sentient beings who dream of becoming human and overreach by asking for maternal love from the blue fairy. When Harshit Agarwal opens his inaugural remarks by talking of the ‘poetics of technology’, one is reminded of how beautifully art can blend with technology, science fiction with fairy tale. Spielberg uses the poetry of W. B. Yeats (“The Stolen Child”) in a film about artificial intelligence to foreground the human urge for quest. One can safely say that Harshit’s work through the use of technological tools creates an important synergy with some very significant aspects of what it means to be human in the contemporary—whether it is through questioning the process of authorship, the open-endedness of artistic style, the non-binary aspects of gender or the process of forming universal ideas of beauty through machines.

After all, aren’t aesthetics, poetics, and sensuality uniquely human? Harshit is prompt in explaining that the AI requires humans to program the codes, feed the images through data sets for it to recognize a pattern, and the repetitive input of data (could be images, colours, data sets) enables the AI to recognize patterns, concepts, and shapes. AI art brings together a shape shifting assemblage of the artist’s desire, the machine’s functionality, and the curator’s discretion. The audience was invited to a walk-through at the inaugural ceremony where we interacted with AI technologies, and Harshit’s vision. What makes this show a significant event in India is that the data sets are rooted in the global south. The inaugural event of the solo exhibition featured a dialogue between Karthik Kalyanaraman, Harshit Agarwal, Ranjan Ghosh, and Myna Mukherjee. According to Karthik, the global unequal distribution of power affects how AI will be used by humans since five major corporations based in the global north dominate AI research. Thus artists such as Harshit, are inverting the uses of AI for surveillance and e-commerce toward creative potentials.

What makes this show stand out is that it opens up a dialogue with certain artistic traditions and representative currencies in the visual arts. Not only does Harshit’s work (Author)rise (ball pen on paper) which looks at the interaction of writing tools with disembodied algorithm, make the audience wonder how machines are changing our cognitive maps—it also asks us how we re-cognize art as such and at which point do we say it is a finished piece? Why should art made by machines be called Art? Re/cognition is an important part of this process—how the machine learns to recognize patterns, at which point the artist recognizes it as art amidst various pieces, and how the curator arranges and interprets relations between older forms of art and the new manifestation? After all, recognition and interpretation are two parts of the meaning-making process.

The piece called Still Life: Icon and Fetish (archival print on canvas with custom frames) talks back to the significant schematic traditions of Western canonical art. The posthuman urges one to think of art as manifestation rather than merely representation—most of Harshit’s works are subtitled as “manifestation”. Myna’s organisation of Still Life through a three-sided open-ended framing with their backs to each other looks like parentheses that refuse to be closed off—thereby conveying that this adaptation of Dutch still life painting is not merely mimicry of a significant genre in Western art, but actually speaks to that tradition in a real way through the use of technological tool. This kind of oddness in framing further defamiliarizes what is already familiar and therefore draws new relationalities with older forms of what we cognitively and canonically know as Art.

That AI art is a collaborative and collective process—right from mining data sets, to creating algorithms through the many layers of curation that finally makes it a dynamic experience—and it is evident from exhibition and the way the show has been conceptualised as an interactive experience. The media used in AI art ranges from canvas to interactive webcams and TV screens, so that the experience of art is tactile, which in turn breaks down the viewer-object divide. In a world where affect is increasingly mediatized and mediated through screens, the interactive power of AI art cannot be dismissed as a phase. Unlike a traditional visual arts exhibition, where the art does not feel the need to signal towards the process itself, this AI art show on the other hand demystifies the process of creating art and Harshit spends a good amount of time ensuring that he talks of the process. In a piece called The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Algorithm (archival print on paper), which looks rather abstract at first glance, Harshit explains the method. This piece is born out of how Harshit teaches ‘an AI what the human inside looks like by showing it several videos of surgical operations and dissections’. This naming not only harks back to Rembrandt’s iconic The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp which is produced in an era troubled by the medical gaze on humans, but also manages to invert that medical gaze by showing us that when the insides of a human are fragmented and seen close up, they too might look like the nuts-and-bolt abstraction which constitute the insides of a machine.

AI Genders?

In the piece titled Strange Genders (a set of two installations by 64/1 [Karthik Kalyanaraman and Raghava K. K.], and Harshit Agrawal, commissioned by Myna Mukherjee for Artissima), the artists traveled around temples in India and asked people to draw stick images of male and female. The artists then fed the images into the AI, after which the AI recognized most accurately the female figures. The computer read every figure as a certain percentage male and certain percentage female. The artists read through the percentages to allocate the AI generated figures a male/female binary. Harshit says:

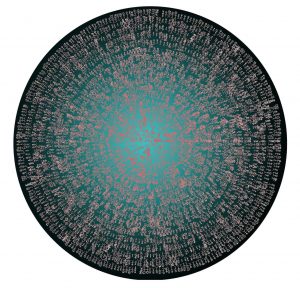

An AI is trained on these drawings and taught how to draw human figures. However, unlike humans, an algorithm trained on both genders, when asked to produce drawings of humans, can only produce an image that has a certain probability of being recognized as, say female, by a second AI which is taught to classify an object on a spectrum from ‘female’ to ‘not female’. Two works of art are created from this process: a poster inspired by the South Indian Saiva Siddhanta concept of the bindu or the female material origin of the universe, and 3 books that catalogue both the (strange) human binary conception of gender and the machine’s (natural?) reconstruction of a gender spectrum.

The stick fingers are assembled on two coloured spherical objects. Manifestation 1 with the red with a halo of ash represents female and manifestation 2 which represents male, the blue with a halo of black. This process questions how medical science assigns the sex at birth and collapses the sex/gender distinction. Thus the sex/gender binary of male-female is a constructed reality and the AI process reiterates how the gender binary is performatively maintained as a norm in society. The proliferation of genders curls up with the most feminine representation at its centre, rather than an intended spectrum which imagines extremes at both ends. Despite its shape, this piece decentres the “universal perception” of gender as well the side-heavy metaphorics of a spectrum, and instead urges the viewer to think of gender as a concept with varying percentages and varying perceptions of male and female. ‘Curatorially, I understand the blue extends from a global south aesthetic and bridges over to the contemporary west. Blue (neel) has many many dimensions in the aesthetics and philosophies of Hinduism. Reflective of south asia, blue [is the] colour of shringara rasa, krishna [who is] lotus eyed, digambari… mandalas, [as well as] blue lotus. [Blue has] aesthetic and philosophical connotations’, says curator Myna Mukherjee. ‘Strange’ is a useful contemporary lens to view both art and gender—not only because it is synonymous with queer, but because art works by making strange that which we take for granted.

Today, AI technologies can generate sensual aesthetics. Further, AI creates algorithms based on big data generated from smartphones and social media. The creeping of technological surveillance into our intimate lives might be a scary idea. Yet, we touch the screen to swipe a ‘like’, share selfies, or grieve at losses through Facebook or Instagram posts. The screen and touch creates an affective loop that tether us to programming codes, ether waves or to AI generated artistic visions as in the case of Harshit’s art. Our intimate lives and the pulsating excitement of seeing the beloved via a screen is both human and machine at the same time. Curator Myna Mukherjee and artist Harshit Agarwal bring forth for us the ‘techno-optimist’: possibilities for an unknown yet newer horizon.

‘EXO-stential: AI Musings on the Posthuman’, curated by Myna Mukherjee with collaboration by 64/1, 11–31 September 2021, Emami Art, Kolkata.